Author’s note: It is not my intention nor implication to accuse anyone of censorship, I just want to provide some snarky commentary about the First Amendment.

First and foremost, I’m not a lawyer and I’m not a journalist — I’m a photographer.

With that out of the way, I’m sure most of the people reading this are aware that in the last week, The Battalion managed to unite TexAgs, Texas A&M Barstool, Old Row, TAMU Affirmations, TAMU Barbz, Leon O’Neal Jr. and almost the entirety of Aggie Twitter. In case you missed that, I recommend you read any one of the numerous news stories published about the situation, though I am partial to our own. But, to give a brief summary, A&M administration demanded The Battalion stop printing, effective immediately, and was asked to make a decision to fall under university purview by the next semester or continue as a student organization without certain resources. Personally, I’m not a huge fan of the ultimatum, but that’s not what this opinion piece is about.

This piece is about the First Amendment, and my opinion is that Aggies online have been doing a really good job in demonstrating why the University of Texas is still home to the state’s premier law school. I’ve seen many people on Twitter, Instagram and Reddit post about the First Amendment in the context of this situation with various levels of accuracy. I’m no 1L, but I did pass Intro to Business Law, Constitutional Rights and Liberties and Communications Law. I’m not claiming I have even taken the LSAT, and I’m definitely not claiming I would pass the Bar Exam but I’m pretty confident that I know more about the First Amendment than you do, genius.

I’m drawing mostly from my communications law class, taught by David Donaldson, Class of 1973, who graduated from “the only acceptable school an Aggie can go to in Austin: UT Law.” He was a damn good professor who taught at UT and A&M, and Professor Donaldson, if you’re reading this, please know I really enjoyed your class. If you’re wondering why I feel this is worthy of note, just search “David Donaldson Daily Mail meme.”

He began his first lecture of the semester by reading the First Amendment out loud to us. That seems as good a place to start as any. Now obviously, I can’t read it aloud to you, dear Batt reader, but please read it in your head the way you think someone who is a retired First Amendment lawyer and cowboy action shooting champion would:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The relevant part there is, “or of the press.” So, what does that actually mean, Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of the press? The nine people who live in Washington, get paid to put on some drippy robes — drippy means cool — and listen to people who get paid even more money to argue about what it means, and over the last 230 years, they meet on Fridays to argue about things in a secret room and then they either agree or don’t. Eventually, one of them writes down their opinion and at least four other people agree with them and write more opinions and it becomes the law.

But what do they argue about? The American legal system is a combination of precedent, history and tradition. American legal history, regarding the First Amendment, goes back far beyond 1789. We have to first understand why the First Amendment was written before we can even understand how it has been applied today.

Sir William Berkley, royal governor of Virginia in 1671, said this:

“I thank God, we have not free schools nor printing; and I hope we shall not have these hundred years. For learning has brought disobedience, and heresy and sects into the world; and printing has divulged them and libels against the government. God keep us from both!”

I think, regardless of your political beliefs, we can all probably agree what he said doesn’t sound very American. Also, it’s not a typo, that’s how they used to talk. His Majesty the King, much like some people today, could not stand criticism, so the British made it a crime called seditious libel. Anyone who made statements critical of the government could be thrown in jail.

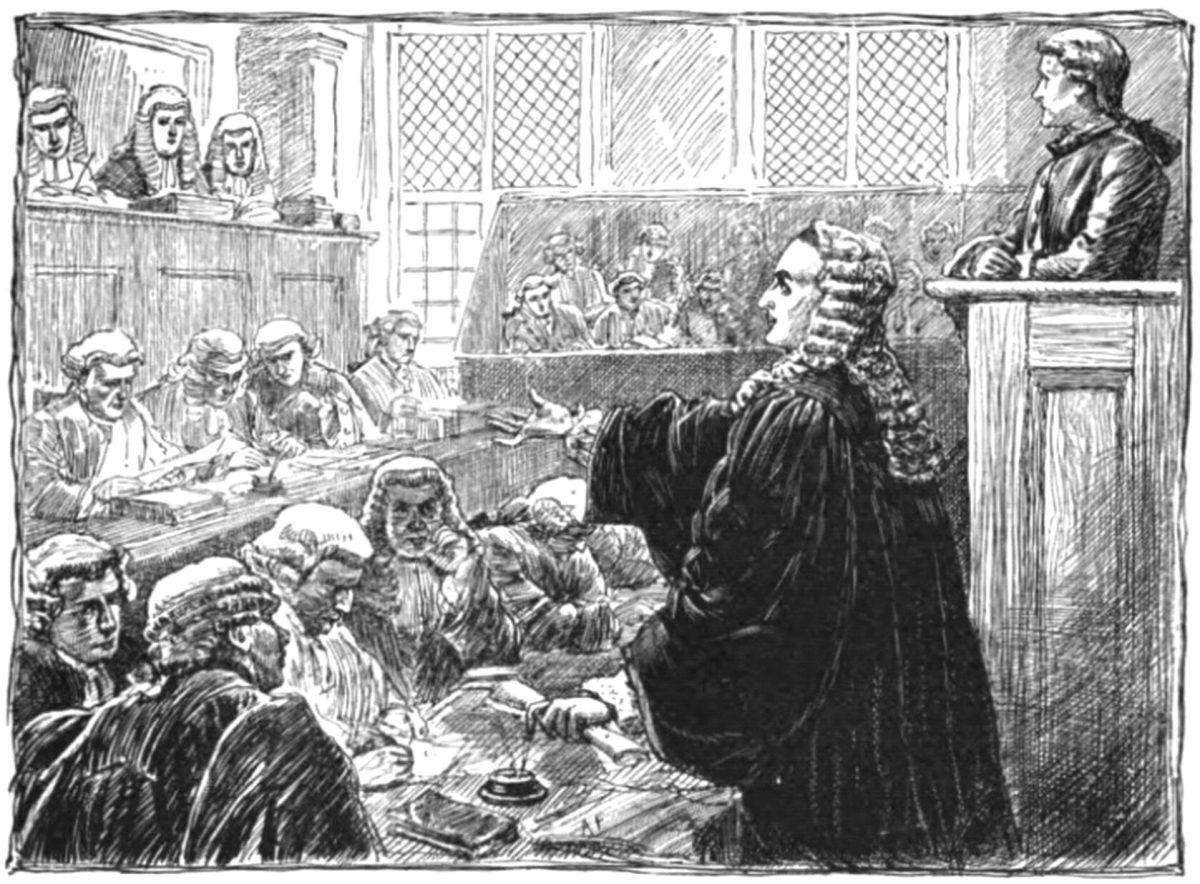

In 1735, exactly that happened. A guy named John Peter Zenger published an article complaining about the local government, and for doing so, the local government threw him in jail. Zenger hired a lawyer named Andrew Hamilton — no relation — who argued while Zenger did indeed publish something that made the government look bad, it was true. So, why should it be a crime? The jury agreed and truth became an accepted defense to libel, and it remains so to this day. And everyone lived happily ever after, and nobody ever got mad at a journalist again.

Ha.

Tongue-in-cheek aside, it turns out, many people have gotten mad at journalists since then, and the Supreme Court has decided journalists are protected by the law, often. As long as they meet professional and ethical standards necessary to publish, journalists are supposed to be able to say whatever they want. Especially if it’s critical of the government.

Government censorship in professional journalism is supposed to be minimal. There are very few instances in which the government can censor the press. The only two real instances are in times of war or instances where the speech invites violence, see Neer v. Minnesota.

Since then, the Supreme Court has proven this barrier is extremely high, allowing The New York Times to publish classified documents during Richard Nixon’s administration. The administration attempted to exercise what is known as prior restraint and obtain a judicial order to prevent The New York Times from publishing what would go on to be known as the Pentagon Papers. In New York Times Co. v. United States, the Supreme Court found that just because The New York Times would likely embarrass the government, it doesn’t put the nation in danger, ultimately ruling that The New York Times was protected under the First Amendment.

Criticizing authority is as much of an American pastime as baseball. Many Americans might think of that whole “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,” quote when they think about free speech in America — funnily enough the spuriously attributed Voltaire and actual author Evelyn Beatrice Hall are French and English, respectively. But, like I said earlier, I’m not a journalist. I’m a photographer who works for a student newspaper, a student newspaper which is 60 years older than the AP Stylebook; a student newspaper at a state university where the university is the government. What has the Supreme Court decided that I get to say?

Well, here’s where it gets tricky and it could take a judge, potentially a panel of judges, to decide specifically what I, as a member of The Battalion, am allowed to do. This comes as a result of the case Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier. One of the many questions raised in Hazelwood is if school newspapers are considered a public forum. In First Amendment law, a public forum is simply a protected place in which speech happens. No restriction based on content may occur in a public forum. Specifically, the question raised in the case is whether school newspapers are limited public forums. Limited public forum is a jargon phrase for a category of public forum established in Perry Education Association v. Perry Educators’ Association, so anytime I refer to a public forum, I mean a limited public forum.

The majority opinion of Hazelwood, written by 1937 Heisman runner-up Justice Byron White, states that curriculum-based school newspapers — where students contribute to the paper as a part of a class — are not forums for student expression. He goes so far as to say public schools “need not tolerate student speech that is inconsistent with its basic educational mission, even though the government could not censor similar speech outside the school.” Now, before you go and jump to conclusions, let the 1938 and 1940 NFL rushing yards leader finish.

White adds, “School facilities may be deemed to be public forums only if school authorities have by policy or by practice opened the facilities for indiscriminate use by the general public, or by some segment of the public, such as student organizations.” By that ruling, as long as school newspapers are produced by students for no reason other than the fact that it is weirdly fun to stay up late making a newspaper, a state university can’t censor the student paper’s content.

What if, as a few people online have argued, it’s an issue of quality, and the quality of The Battalion doesn’t meet the level of an institution that is the prestigious farm school of Texas A&M, the world-class research university where we scream nonsense at midnight and worship a dog and where we embrace the fact that other schools call us a cult. What if we make a newspaper that is so bad, we sully that reputation?

Aside from the fact that by an actual quantitative metric, The Battalion is the sixth best college newspaper in the country, it wouldn’t change anything. In a 2001 case before the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, Kincaid v. Gibson, school officials refused to allow a student-run yearbook to deliver their finished print because they thought the yearbook was of low quality and “inappropriate.” The court found that college students, believe it or not, are adults, and should be treated as such — unless you write something like “Bong Hits 4 Jesus.” That’s a whole different story though, so you’ll have to look that one up on your own.

The judge who wrote the Kincaid opinion, R. Guy Cole Jr., did what I will describe as the legal equivalent of that unofficial yell Head Yell Leader Memo Salinas had to write a letter about last fall. He says calling something low quality is an issue of content. I’ll just let him take it from here:

“There is little if any difference between hiding from public view the words and pictures students use to portray their college experience, and forcing students to publish a state-sponsored script. In either case, the government alters student expression by obliterating it. We will not sanction a reading of the First Amendment that permits government officials to censor expression in a limited public forum in order to coerce speech that pleases the government.”

Public universities are a hotbed for First Amendment issues. That’s why groups like Foundation for Individual Rights for Education publish rankings for how different universities compare when it comes to support for the First Amendment. In my research, I found a paragraph from Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in Rosenberger v. University of Virginia, and while that situation in that case is not the situation in every other First Amendment case, I still feel it perfectly summarizes what the First Amendment means on college campuses:

“The first danger to liberty lies in granting the state the power to examine publications to determine whether or not they are based on some ultimate idea and, if so, for the state to classify them. The second, and corollary, danger is to speech from the chilling of individual thought and expression. That danger is especially real in the university setting, where the state acts against a background and tradition of thought and experiment that is at the center of our intellectual and philosophic tradition.

“In ancient Athens, and, as Europe entered into a new period of intellectual awakening, in places like Bologna, Oxford and Paris, universities began as voluntary and spontaneous assemblages or concourses for students to speak and to write and to learn. The quality and creative power of student intellectual life to this day remains a vital measure of a school’s influence and attainment. For the university, by regulation, to cast disapproval on particular viewpoints of its students risks the suppression of free speech and creative inquiry in one of the vital centers for the nation’s intellectual life, its college and university campuses.”

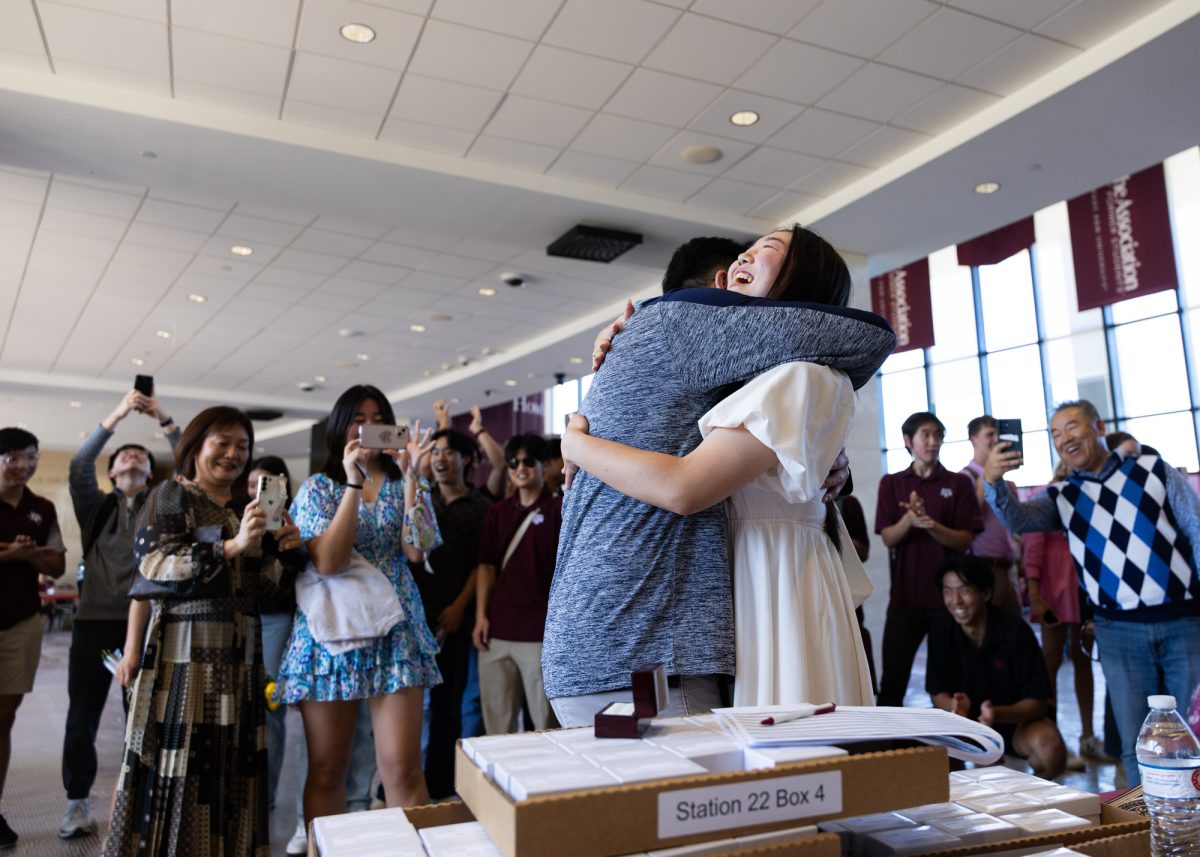

The Battalion is a student organization. Any student at A&M is welcome to apply to be a writer or photographer. But, as long as I have been a student here, faculty — including the Texas A&M System chancellor — have been welcomed as guest contributors.

The content of the newspaper should not be influenced by anyone other than current A&M students. It is the students who are supposed to write the stories, take the pictures and design the paper. It is ours to make, ours to screw up and ours to learn from. As the very first editors of The Battalion said in the inaugural edition, “Boys this paper is yours. Make it something. Lend all your assistance possible. It is your duty, and should be your pleasure, to write something for every issue. The editors will endeavor to obtain most of the contributions from among you, and as it will prove beneficial in more than one way, you ought to be proud of the opportunity.”

So, if you’re a former student who has an issue with the content in The Batt, I’m glad you feel like you’re still in Aggieland, but you’re not. You don’t get a say in student life anymore, your time here is done. It’s a college newspaper, for college students. That’s the purpose of our publication: a campus forum for current A&M students to enter their thoughts into the marketplace of ideas. So, current students, please contribute. Share your ideas and let the best idea win. That’s the whole point.

Robert O’Brien is a political science redshirt senior and photo chief for The Battalion.

Analysis: A photo chief’s guide to the First Amendment

February 17, 2022

Photo by Illustration by Martha J. Lamb

The Famous Zenger Trial as it appeared in the book “Wall Street in History” in 1883.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$1015

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!