The night started with the smell of pungent, barely-contained fervor. My friends, all toting beautifully-kept bibles and time-worn journals, led me to a cramped seat in Reed Arena facing a brightly-lit band at the center of a mass of impatient faces. As I was just beginning to notice the surprising lack of melanin in the crowd, I felt the temperature rise by a couple of degrees when the guitarist suddenly banged out a major chord. Like flipping a switch, at least three-fourths of the crowd stood up and started to yell out the lyrics to the song. However, I felt a weight of hesitation keep me down as I tried to rise to join my friends. This was just so foreign, so alien to me, and not at all what I had expected.

I always knew that I was a significant minority at Texas A&M, but my first time at Breakaway was when I truly had to internalize it. Coming from a Hindu background but being an atheist has automatically made me dissimilar to what I would guess is over 80% of the students at A&M. Contrary to my hope before coming here, religion does have a very real effect on this campus and the students who live here. It is an important trait that one can use to network, to make friends, to find potential dates — all of which I had observed throughout my life already.

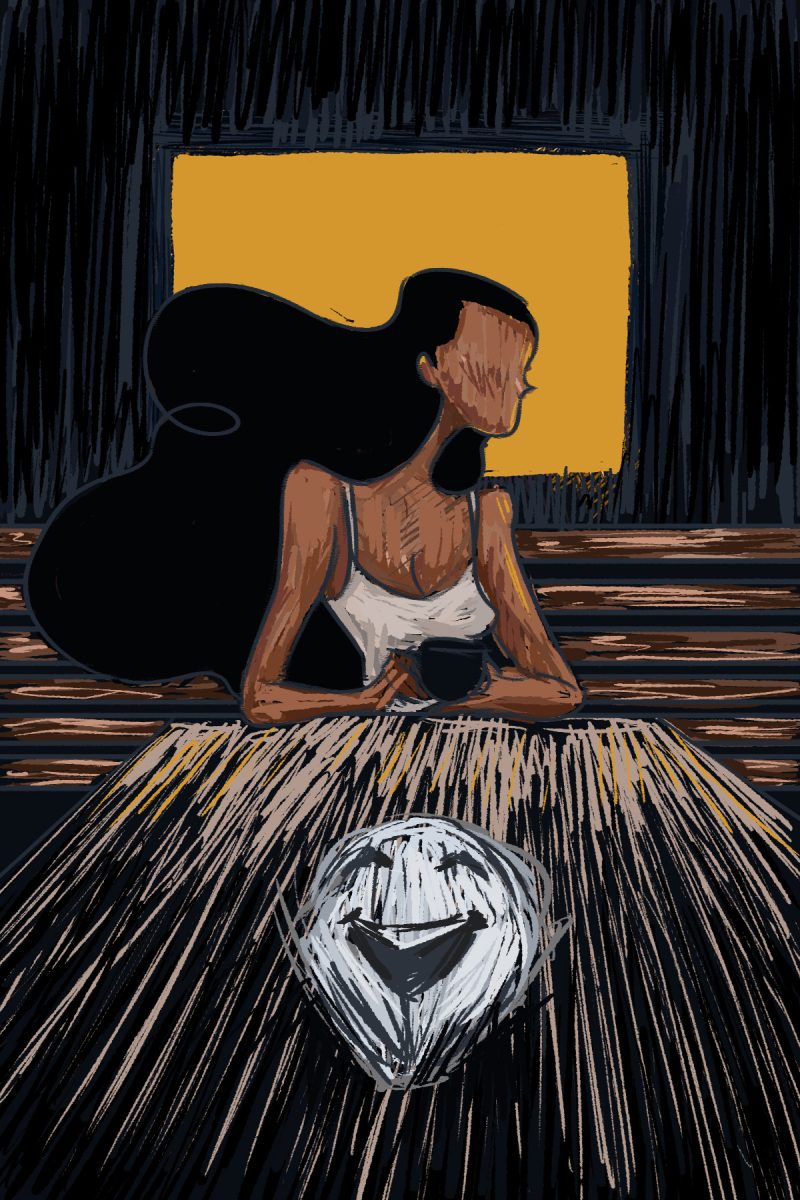

However, being an outsider at this event allowed me to capture some of the oddity of the situation. The one moment that struck me the most was when several people around the arena seemed to simultaneously raise their hands to the sky while singing along. Eyes closed, body quivering, these people seemed to be groping for something that only they could sense. Like wildfire, more students joined in, until eventually I was surrounded by people reaching for something more than just the air they closed their hands upon. While I presumed that they were reaching for the “hand of God,” and my friends later confirmed that suspicion, at that moment I was very confused as to why it seemed like the audience had lost all control of themselves.

Though there was also a much calmer Bible study and another few songs, I couldn’t get that scene out of my head. I went to leave with my friends, and I asked them if Breakaway is always like this — they answered in the affirmative. But when I asked whether going to church is this exciting, I received hesitation and a few shakes of the head. Someone then said, “I don’t go to church as often as I go to Breakaway. I don’t like the pastor telling me I’m gonna go to hell all the time.” As I continued talking with my friends, I saw that for some of them Breakaway was the extent of their religious activity for the week.

Breakaway, then, is not just a feature of some students’ religion but is the focus of their religious life. For many people, religion emphasizes self-sacrifice, which is fairly unattractive for most people nowadays. Similarly, going to church and hearing a pastor scream hellfire is likely a punishment unto itself for many young Christians. While not every church or pastor is like that, of course, I have heard enough stories to draw the conclusion that Sundays can be more stressful than they are transformative. That is where Breakaway steps in, which is far more engaging in many ways than traditional expressions of the religion.

While I have talked much about what I think Breakaway is, I would like to close out with a story testifying to one of its realities. When I first walked into Reed Arena, a woman with free Bibles politely jammed one into my hand. Confused at what just happened, I gave it back to her and told her that I did not really want one because I was not Christian. She quickly blurted, “What, then why are you even here?” before realizing the insensitivity of the question. The tide of people started to take me away, and I left before I could answer. I did not think much of it, but after the event was over, I ended up passing by the same woman. I did not really notice her until she grabbed my arm, and I turned to her slightly annoyed that she was stopping me from getting home. She said something like, “That was so stupid of me earlier. I guess I did not realize that non-Christians would come, but we’re super glad to have you here.” My irritation melted as I heard the genuine remorse in her voice, and I thanked her for the apology. Despite my belief that what I had seen throughout the event was through the lens of someone who was not a part of the group, I realized I was never truly unwelcome. I did not even have to be a Christian to find a place there. I could just be myself.