Listening to the “Fearless” album at age 15, I felt empowered.

To the past version of me that spread Pre-Cal notes across my bedroom floor and listened to the album on repeat after band practice, Taylor Swift’s songs were anthems for heartbreaks, back stabbings and other painfully embarrassing adolescent moments. It was the lens through which I saw relationships, the same lens a lot of 15-year-olds saw the world through.

Swift was synonymous with early high school, and when “Red” came out I was eager to learn more about the adult Taylor Swift and her new hear-me-roar brand.

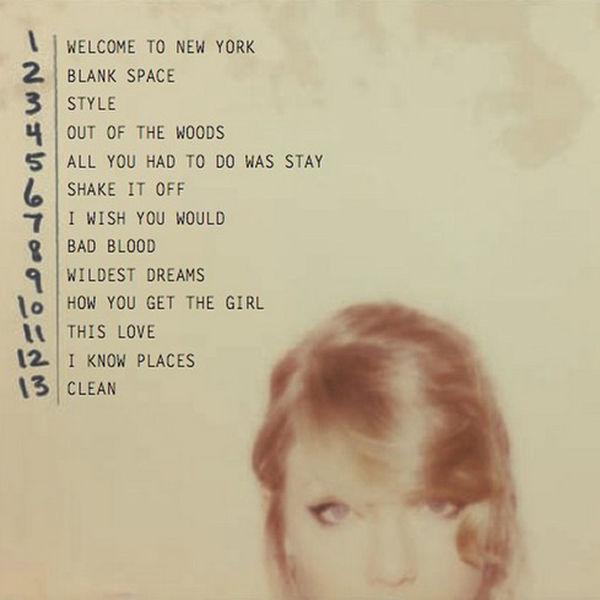

If the intended message wasn’t clear enough with “Red,” it’s clear with “1989” — Taylor Swift has grown into a woman who wears red lipstick, loves hard, crashes easily and doesn’t apologize for going after guys with a “James Dean” style.

The heartbeat of the album is explicitly stated with one line, “I could make the bad guys good for a weekend.” With the clichés and quirky sounds that date the pop genre, Swift tells us to dive in.

But there are cracks in this message. What Swift proposes we dive into is a sexually active version of the same cheap romantic relationship-obsessed music I listened to years ago.

I want so badly for “1989” to reflect where I’m at in life. I want the music to have developed with me, into something more than the boy craze I’ve long outgrown. I want depth. I want the adult Swift to tackle problems in society, to hit on something that matters — anything that matters — but the album falls flat.

It’s the same crap we feed girls for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Halfway through “1989,” all I could think about was my 15-year-old sister listening to “1989.” And for the first time, listening to Taylor Swift terrified me.

It’s so important to be able to express the free spirit that “1989” conveys. It’s so valuable to embrace insecurities and love and hurt, but this album’s presentation of only a narrow perspective on a small segment of life is a problem.

Swift is a role model for girls by virtue of being one of the most prominent women in the media. By singing about romantic relationships 95 percent of the time, the girls consuming this material are left with the same obsession, the same sense of self identification in terms of relationship to man.

As a society, we need our girls to understand that these songs are not grounded in reality — that reality is so much better.

When “Wildest Dreams” offers a picturesque scene of a woman staring at the sunset in a dress, we need girls to understand it’s okay to aspire to be more than a passive woman of some man’s dreams.

When “Style” offers two relationship options — burn in flames or find paradise — we need girls to understand that relationships are so much more than the extreme highs and the low, that the real value in a relat ionship comes from mutual respect.

When “Shake it Off” comes on the radio, we need girls to understand that the natural manifestation of brushing off unfair criticism is not necessarily lashing out with the “fella over there.”

When “Bad Blood” denounces a former friend for crimes “time won’t heal,” we need girls to understand that part of growing up is learning not to let hate consume you, to take the lessons life teaches you and move on with grace.

With her insane talent and public platform, Swift has the means of really furthering her “girl power” brand by presenting something more than the same old pop rhetoric that a woman is interesting if enough strangers are willing to have sex with her to the backdrop of city lights.

It’s so easy for me to call Taylor Swift a feminist’s nightmare and then call it a day, but that isn’t fair. Who am I to say that her music is any less sincere because it reflects the stage of life she is in? Who am I to thrust civil responsibility onto her, to say that she shouldn’t make millions doing what she loves?

This is what makes the whole scenario sadder. If Swift’s songs showed greater scope of understanding, it would only be a start. The problem is systemic and runs deeper than any one iconic woman and one pop album. Even Swift.

In the end, listening to “1989” at age 20, I just feel powerless.

Aimée Breaux is a junior applied mathematical sciences major and managing editor for The Battalion.

New songs, same old message

October 28, 2014

PROVIDED

0

Donate to The Battalion

$1765

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!