People are dramatic. We always have been, and likely always will be. But unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past decade or so, you’ve probably noticed that Gen Z drama has a strange new way of being expressed: through the inappropriate adoption of mental health issues and disorders.

“I definitely have ADHD. Like, I haven’t stopped scrolling on TikTok for three hours now, and I haven’t even studied for my midterms yet! I should get checked out or something.”

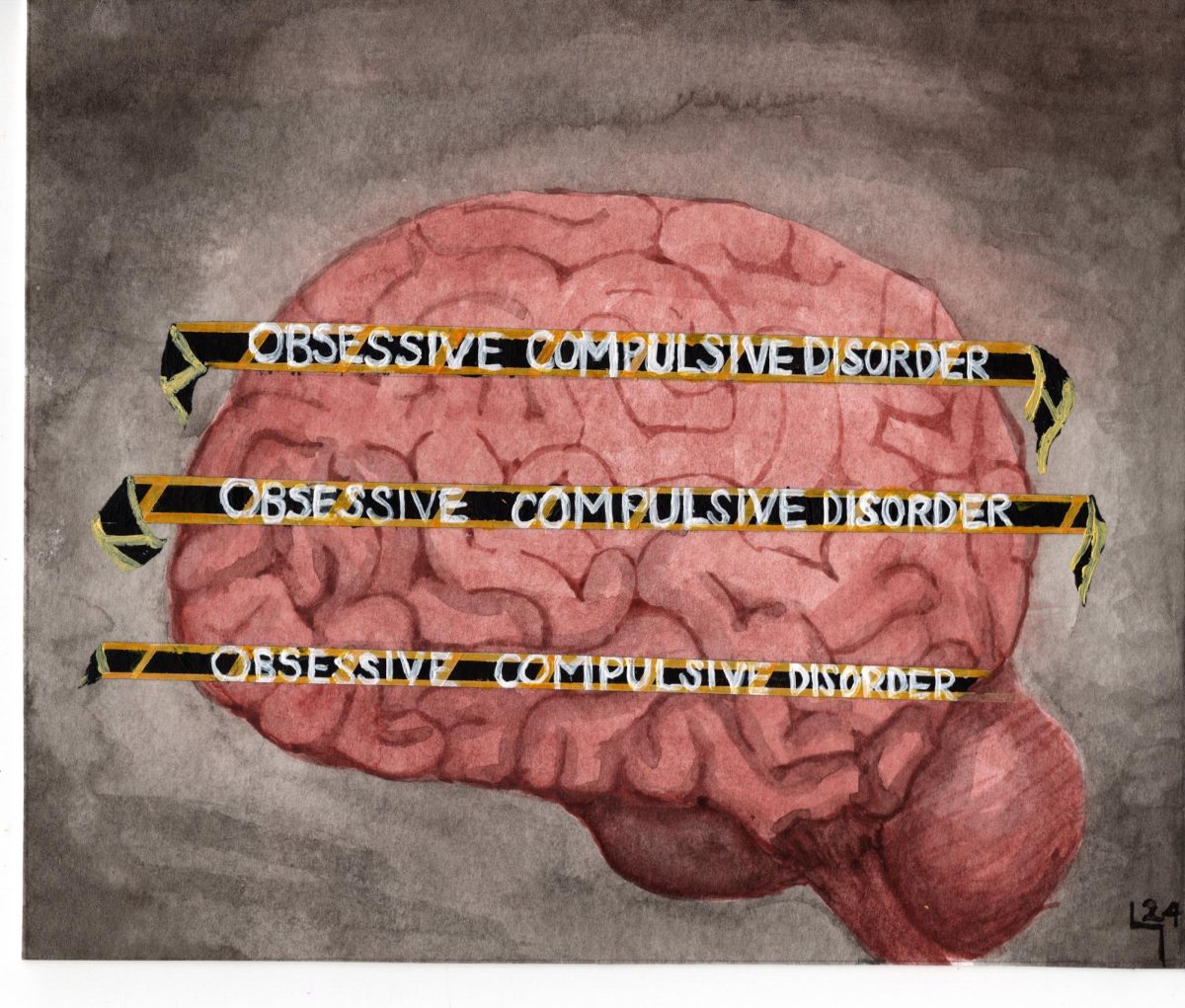

“I literally am so OCD, like I can’t even. My apartment literally ALWAYS has to be clean. I just hate it. Ugh.”

Even if you’re lucky enough to have never heard someone say these things unironically — and honestly, we probably all have said something like that at some point — you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about just by watching endless videos online.

Self-diagnosing from ADHD to depression, it’s clear that some people want to categorize themselves in a way that explains their activity using whatever label is most convenient. Instead of accepting the obvious conclusion — that people might just have different behaviors that don’t quite fit into the “normal person” box — they instead use terms meant for clinical diagnoses on themselves with no regard for the real conditions behind them.

Even though most people do this without intending any harm, this practice of taking clinical terms lightly leads to massive problems.

Why? Because people who self-diagnose with these conditions change the meaning of the words and make people who actually suffer from these problems seem as if they are dealing with basic, everyday issues. In reality, things can be — and often are — far worse.

And I can speak to that personally.

When I was seven years old, I distinctly recall swallowing — and subsequently choking on — a mint. As my family rushed to my side to see if I was alright, I was struck with a new, distinct terror: I really felt like I might die in that moment, at seven years old.

Thankfully, the mint was safely dislodged a few seconds later, but that had been enough for me. I was mortified. Maybe I overreacted, but what happened next wasn’t fun anyway.

Over the course of the next month, I refused to eat anything but the most liquid foods. So I lost weight. A lot of it. Five pounds, 10 pounds, going on 15; every week, I watched the scale drop further and further. I was a skinny kid, but I was getting even skinnier.

I cried at every single meal. Even though I wanted to eat so badly, I just couldn’t get anything down no matter what I did. I was exhausted, and I didn’t want to know what would have happened if I had gone much further.

I was able to adjust back to normal food eventually, but the scars remained. I had developed a periodic fear of choking, and it would come back two more times in the next few years. Even now, I still choke up when I eat food the wrong way or think about that time in my life.

Unfortunately, however, I haven’t been able to tell many people about my past phobia, even though I think it formed a crucial part of my early life.

That’s because the word “phobia” — like “ADHD,” “OCD,” “depression” and a few other similar conditions — now has two main meanings: one meaning is serious and typically refers to a diagnosable condition, while the other refers to isolated actions which somewhat resemble symptoms of those conditions, but have none of the same underlying causes.

This change in meaning happens through a process called semantic shift, in which the common usage of a word shifts from its original meaning to a related, although substantially different, set of ideas. It’s usually not intentional — in fact, it’s often not even noticeable at times — but it is a process that often seriously detracts from or adds to the meaning of terms originally meant for specific uses.

In short, this means that whenever someone with a legitimate mental issue wants to talk about themselves or express their struggles, people will often misunderstand them as complaining about basic problems that most people experience on a daily basis. Even if that person clarifies that their condition is serious, the meaning is still reduced by the casual usage of the diagnostic terms.

So, what should we do about this, then? Maybe we should just consider making up new words instead?

Maybe I could reach out to the people behind the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, and ask them to publicize new terms for these conditions. That would effectively reset the semantic field, and it’s probably the quickest and most efficient way to solve the problem for now

Unfortunately, something tells me they’re not going to listen to an undergrad philosophy major’s ramblings about the names of mental conditions.

Although the shift of the overall semantic meaning is inevitable, the best way to slow the problem and do something to help others at the same time is to change your semantic field. Not everyone is going to change, but if someone you know — even you yourself — is struggling with a serious mental issue, you can change the environment by being clear and precise with your words.

We can’t help everyone, but even being an outlet for just one person in need makes a difference. And who knows, maybe the DSM will listen to me someday.

Kaleb Blizzard is a philosophy sophomore and opinion writer for The Battalion.