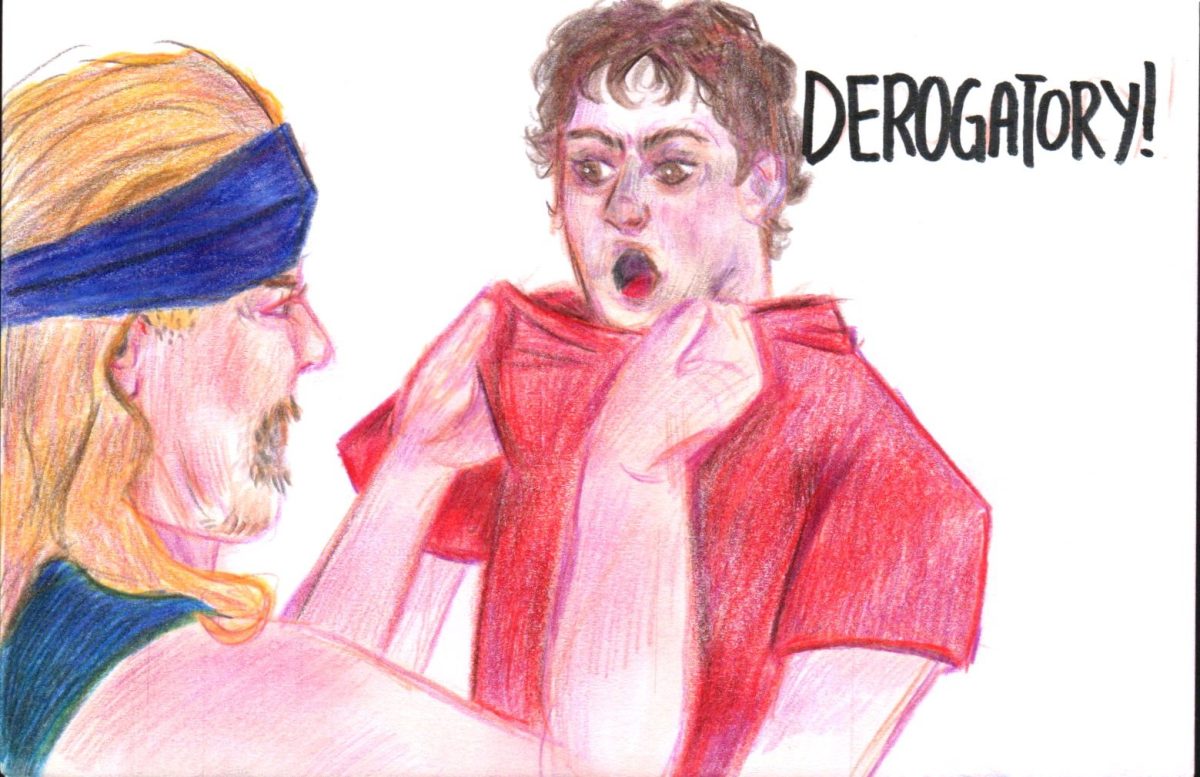

When I was in speech and debate my sophomore year of high school, I had one encounter that left me confused for years. My opponent and I were debating whether universities should restrict constitutionally protected speech. I opposed limitations while my opponent supported them. My opponent said it was in minorities’ best interests to remain silent if they encountered hate speech. As an Asian man, I was astounded that a white person would dare say anything like that, so I argued he was being racist. I lost that debate, and it wasn’t until I read “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” in Harper’s magazine that I understood why. Instead of engaging with my opponent’s argument and demonstrating why he was wrong, I attempted to win with an ad hominem attack. My argument convinced no one that didn’t already agree with me. Unfortunately, some on the left are falling into the same trap. While attempting to pursue the noble goal of empowering minority voices, “cancel culture” is also undermining both social progress and free thought.

In his New York Times column, Ross Douthat gave one of the best definitions for cancel culture I’ve seen. According to Douthat, “cancellation, properly understood, refers to an attack on someone’s employment and reputation by a determined collective of critics, based on an opinion or an action that is alleged to be disgraceful and disqualifying.”

Osita Nwanevu, writing for the New Republic, provided an excellent defense of cancel culture. Her central argument was that individuals have the right to associate with groups of their choice. Nwanevu contends that newspapers have the right “to decide what and whom they would or would not like to publish.” She also states that it is not “unreasonable” for staffers to argue against their editors publishing pieces that conflict with the publication’s values.

But while I agree that, in theory, there is nothing wrong with staffers revolting against their editor, I diverge from Nwanevu’s analysis on two fronts.

First, there are limits to what revolts should be considered acceptable. Consider the case of New York Times Opinion Editor James Bennet, who lost his job after backlash related to the publication of Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton’s controversial op-ed about deploying the military to curb rioters in the wake of George Floyd’s death. Calling in the military to disperse rioters borders on authoritarianism, and America is not a warzone, so soldiers are not necessary. While Bennet absolutely should have read Cotton’s article before running it, he should not have been forced to resign for publishing the piece.

When Bennet published Cotton’s article, backlash centered more on Bennet’s decision to publish the op-ed than on the article’s content. Instead of criticizing Cotton for his hawkish opinions, and possibly converting readers who agreed with Cotton over to our side, many people on the left shot the messenger. Instead of cancelling the editor, those who disagreed should have written a series of response essays that detail why Cotton was wrong. Instead of cancelling Bennet, the left should have exclusively relied upon sensible policy solutions to ameliorate Cotton’s racism. But what resulted was an outpouring of sympathy for Cotton. Not only did the left shoot the messenger, they also shot themselves in the foot.

Second, although newsrooms have the right to publish only what aligns with their values, doing so, if too restrictive, is counterproductive to the press’ legitimacy. Between 2018 and 2019, both CNN and Fox News became more polarized according to a Morning Consult poll. To many, CNN is as much a liberal propaganda machine as Fox News is a conservative one, making it more difficult to persuade someone on the other side of the aisle. Take it from a former debater, it’s much more difficult to convince a judge that you’re right if they don’t like you.

“A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” has drawn significant criticism from other writers and journalists. In a response letter, critics claim that Noam Chomsky, J.K. Rowling, and other signatories fail to address who has power and a prominent voice in public discourse. However, firing editors who publish controversial articles or defaulting to the “you’re racist” argument does nothing to expand marginalized voices. Cancel culture is well-intentioned, but unfortunately it results in nothing but squabble on Twitter and good people losing their jobs.

Will the three left-wing people who read my work try to cancel me? I have no clue. Angry conservatives on Facebook have already “cancelled” me plenty of times. However, I do know that open discourse is the only way we can change institutional norms. We should seek to expand mainstream opinions, but we also cannot alienate views that we find abhorrent or even bigoted. Firing publishers doesn’t do anything to solve social problems. Only discussing policy will result in lasting change.

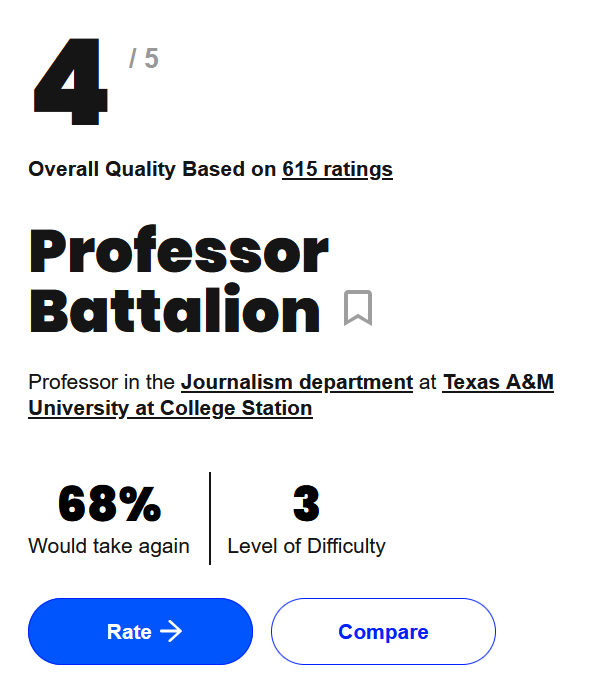

Caleb Powell is a biomedical engineering sophomore and opinion columnist for The Battalion.