It was a relationship that could only come about through divine intervention.

Rob Childress, Texas A&M’s baseball coach, spent the first decade of his life in Jonesboro, Arkansas, an hour northwest of Memphis, Tennessee, in the northeastern corner of the Natural State. But at 10 years old, Childress’ parents divorced and he moved with his mom to Texas to be closer to her family.

The move brought Childress to Harmony, an unincorporated rural community nestled deep in the piney woods of East Texas where the number of Baptist churches (six) far outweighs the number of grocery stores (zero).

With his dad no longer in the picture, Childress said he was searching for a father figure, and it was in that quiet, unassuming little town that he found one.

Finding Harmony

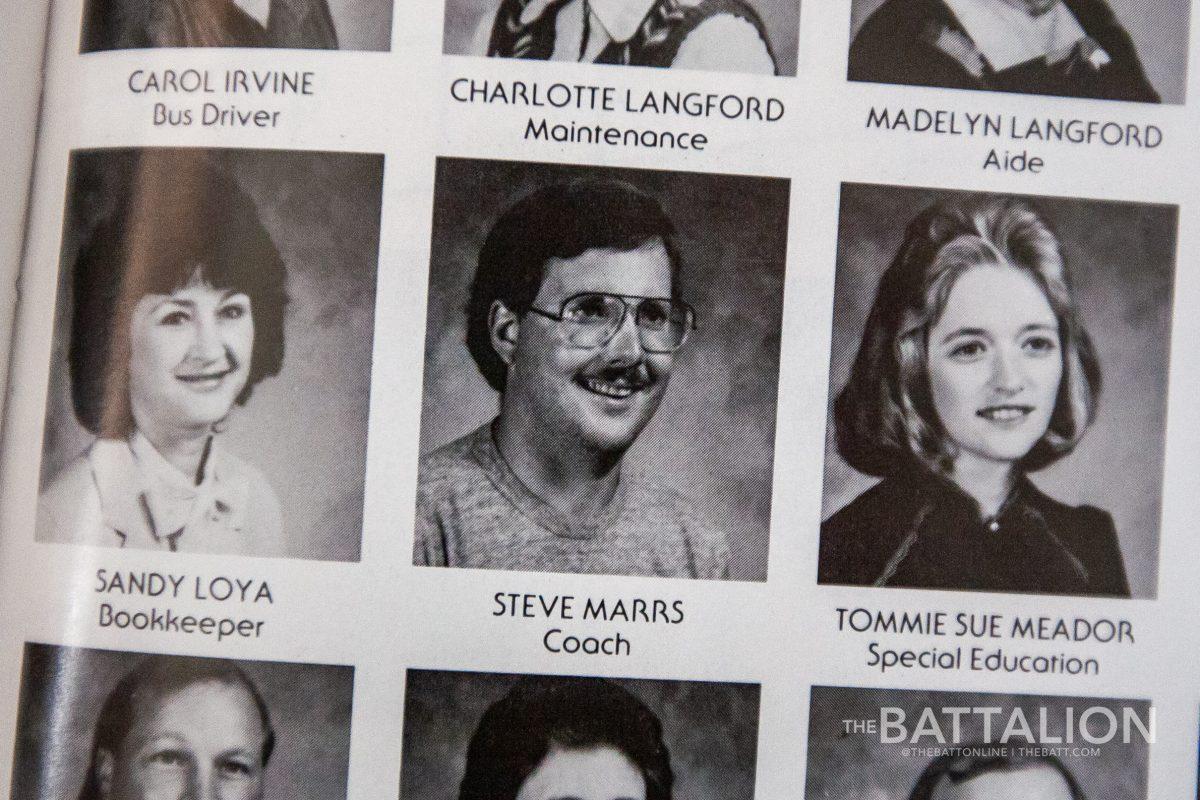

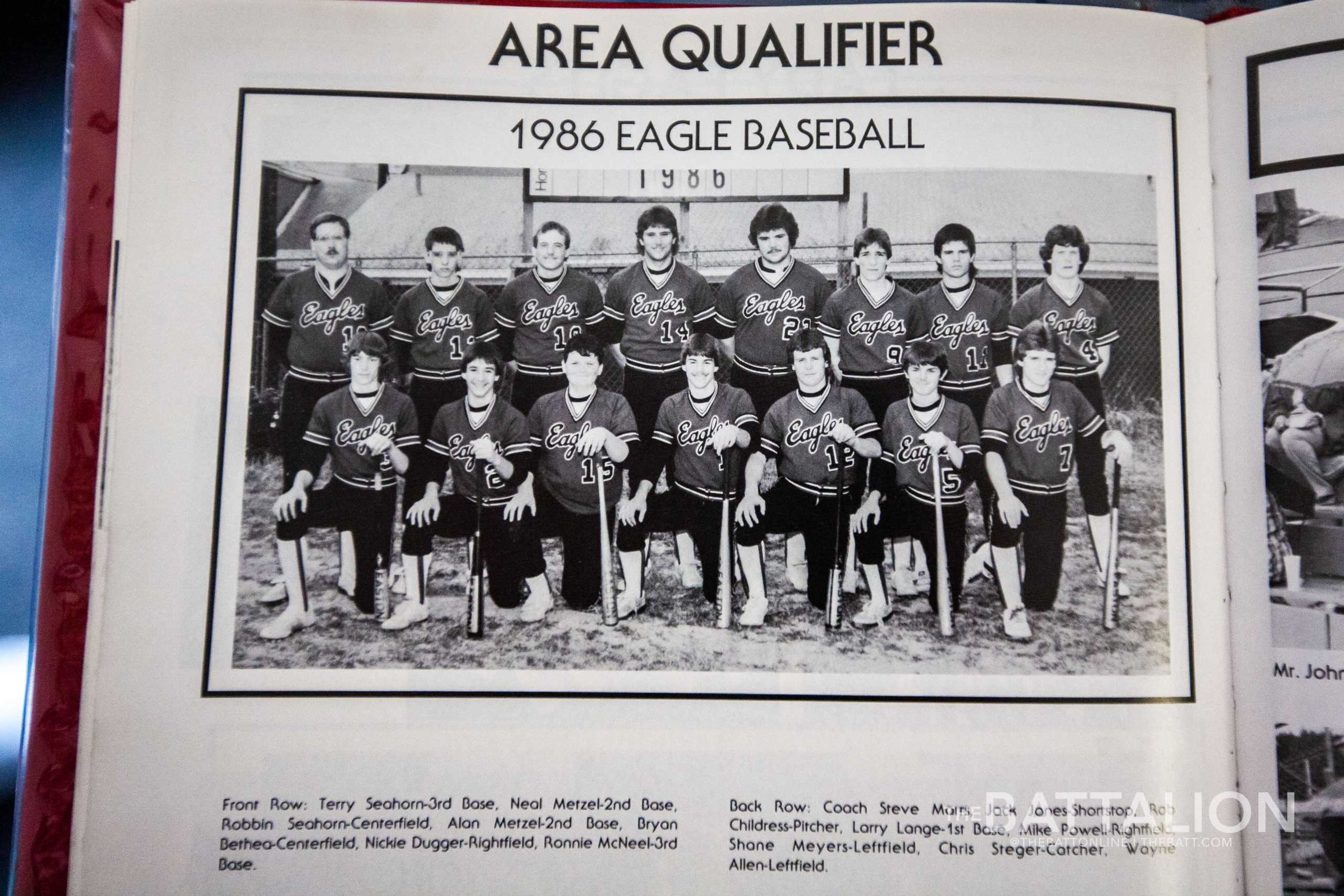

By the time Steve Marrs got to town, Childress had already been at Harmony for a year. But once they met in a physical education class Childress’ freshman year, there was an immediate connection both say was more than coincidence.

Harmony sits isolated along Highway 154 with Gilmer to the east and Quitman to the west. It isn’t very often that someone with no connections to the area moves in.

However, that’s exactly how Marrs got to Harmony.

By the time he arrived, Marrs was right out of college where he spent four years as a left-handed pitcher for Harding University, with his first coaching job taking him almost 300 miles from his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“How a guy from Tulsa, Oklahoma, by way of Harding University in Arkansas finds his way to Harmony, it’s truly a God thing,” Childress said.

Upon graduating college, Marrs had no job lined up due to the demanding schedule of baseball season and was a disc jockey on Sundays at a local country and western radio station when he received an unexpected call.

Harding’s head football coach called Marrs about a friend that was the principal of an East Texas high school. He said the school needed a baseball coach and thought Marrs would be the right guy for the job.

“I didn’t know where Harmony, Texas, was,” Marrs said. “He said, ‘Harmony is seven miles west of Gilmer.’ I didn’t even know where Gilmer was.”

Marrs said he had only $5 in his wallet at that time and had to ask his dad for gas money to drive down to Texas for the interview. But his prayers were answered when, sitting in the superintendent’s office at Harmony Independent School District, he was offered the job.

He accepted it right away.

It seemed as though the stars were aligning for Marrs to get the job, because not only was there his connection to the high school’s principal, but Marrs and the superintendent had something in common as well. Marrs’ alma mater was a Church of Christ college; the superintendent was a deacon at a local Church of Christ.

The job brought him to the middle of the Piney Woods, a far cry from the nearly 361,000 people living in Tulsa at the time, according to the 1980 census.

“I ended up down here, and there’s no reason I should be down here,” Marrs said. “It was just out of the clear blue until I looked at it later in life. I think God needed me to come here.”

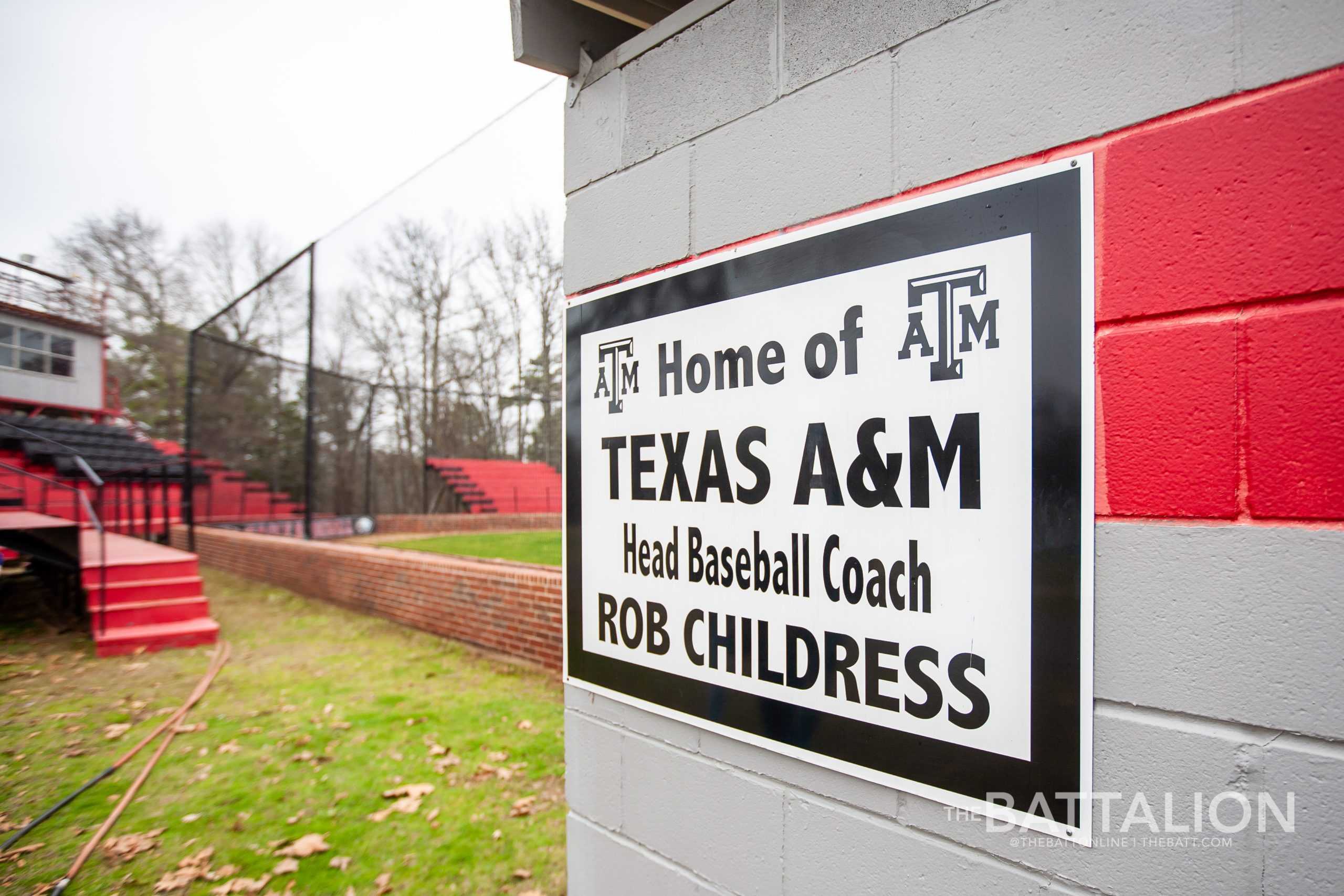

A baseball home

When the pair finally met in 1982, Childress wasn’t in athletics; he wasn’t playing football; he wasn’t playing baseball. He also said he wasn’t sure Marrs would even let him into athletics to play baseball.

“I think when he found out I was left-handed, he gave me a chance,” Childress said.

For Marrs, the choice was a little simpler than that.

“He had a tremendous desire to participate, to be a part of the team,” Marrs said. “I knew he would be a great teammate, so it was a no-brainer letting him in.”

The similarities between the two were abundant. Both were left-handed pitchers. Both were freshmen at the time they met — Childress a freshman in high school and Marrs a freshman coach in his first year out of college.

It all culminated at Harmony High School, with a lifelong relationship developing in the strangest of places: a librarian’s basement.

At the time he moved to Harmony, Marrs was not married and lived in the school librarian’s basement. Often, Childress and a couple other players would visit Marrs to play a video game and talk baseball.

It was during those times that the pair’s relationship began to grow into much more than a player-coach dynamic.

“It didn’t take long for him to be such a huge influence in my life and somebody that I admired and somebody that I looked up to and wanted to please,” Childress said.

The fact that Marrs was unmarried and had no children allowed him to give Childress the attention he should have been getting from a father.

“It’s not anything I wouldn’t have done with a lot of other kids,” Marrs said. “But it just so happened with him, it was a time in his life when he really needed that, and I was more than happy to be that figure for him.”

With Marrs leading him, Childress found a passion for baseball that shaped him both on and off the field.

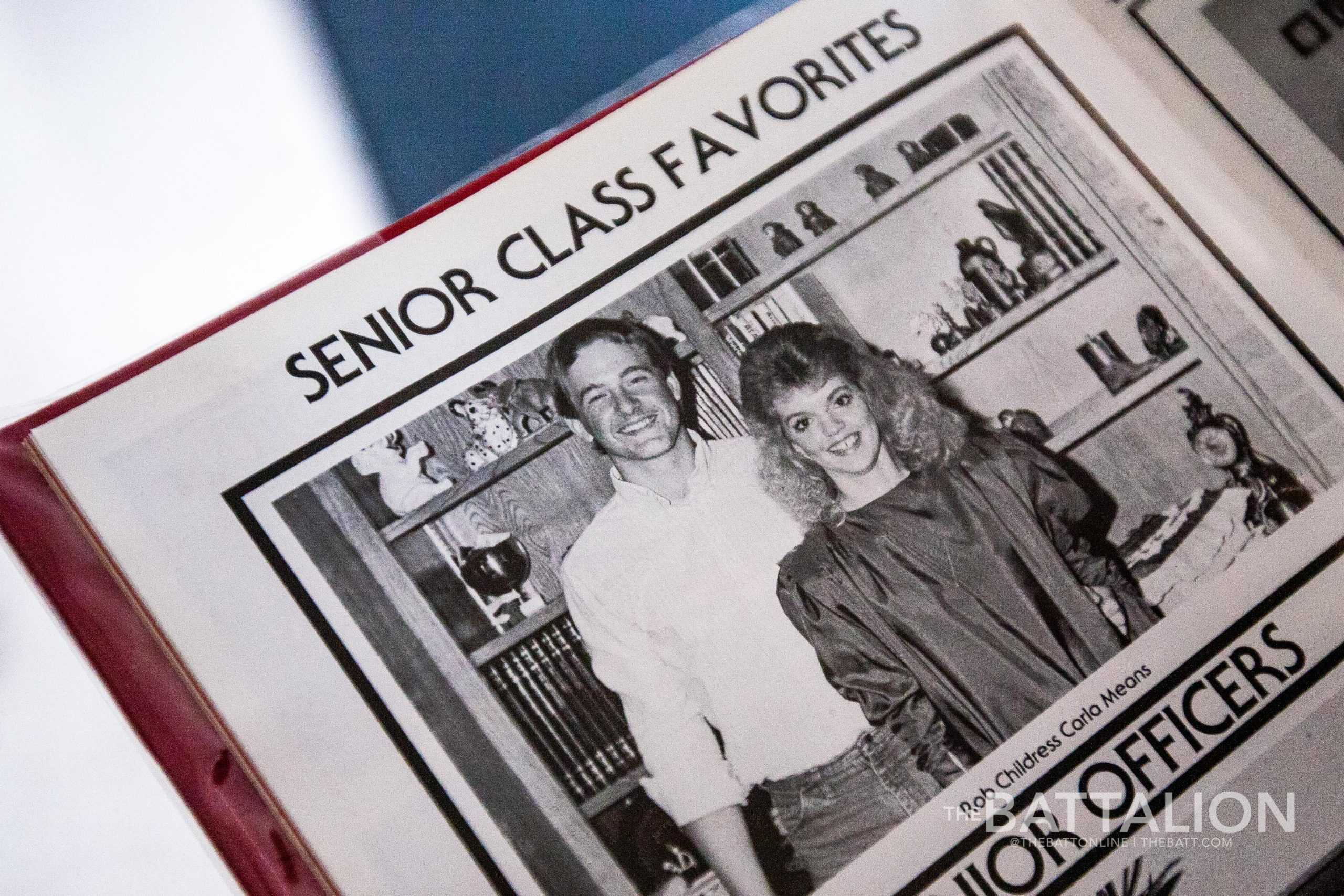

During his senior year, Childress was voted Most Dependable and Best Sense of Humor, the latter of which Marrs said was the antithesis to his personality on the mound.

“He was a happy-go-lucky guy, a lot of fun, a lot of kids really enjoyed him and he had a lot of friends, but when it came to baseball, he was very serious,” Marrs said. “He was a real student of the game.”

It was that dedication to the game that drew Marrs to Childress.

“It was obvious to me right off the bat that he was going to be a tremendous success because of his knowledge and his love for the game,” Marrs said. “He was a sponge.”

Beyond the call of coach

Marrs’ decision to step in and become a father figure for Childress changed the course of his life. Had he not found a home in baseball, the next step for Childress would have been the military.

“I wasn’t going to stay in East Texas and haul hay and milk cows,” Childress said. “Baseball or the military were the two ways out for me to change things, and I’m glad that baseball worked out.”

Marrs knew this, so he did what he could to help Childress succeed. That included driving him over 500 miles to Salina, Kansas, to meet with a college coach.

“He wanted to give me an opportunity to play beyond high school,” Childress said.

But Childress acknowledges there was a chance he didn’t end up in baseball.

“Somewhere along the way, had I ended up with a jerk of a coach, what would my life look like? What direction would I go?” Childress said. “God has always put someone in my life that has kept the direction going with sports.”

Childress had positive experiences with both Marrs and his college coach at Northwood University in Cedar Hill. In Marrs’ case, it was a desire of the coach to build personal relationships with his players and to know them as people, and the effort he put into doing that is what made him special, Childress said.

“He could always make you feel like you were maybe so much more talented than you really were, and that’s a true gift,” Childress said.

That was a lesson learned from Marrs’ own playing experience.

“There’s a lot more to being a ballplayer than just ability,” Marrs said. “I’ve seen a lot of talented guys that have failed in this game. I’ve seen a lot of guys who weren’t very talented who have been successful. I would probably include myself in that category.”

Marrs learned early in his career that the opportunity he had to influence young lives was much more important than the wins he could earn on the field.

“I can’t teach everybody to be a great athlete, but I can teach everybody to be a great human being,” Marrs said. “That became more important to me.”

That mindset inspired the way Childress approaches coaching.

“You’re going to give more if you care more, on both sides as a coach and as a player,” Childress said. “He certainly cared about me, there was no question in that, as a person first and a player second, during those years of my life and, gosh, for the last 35 or 40 years.”

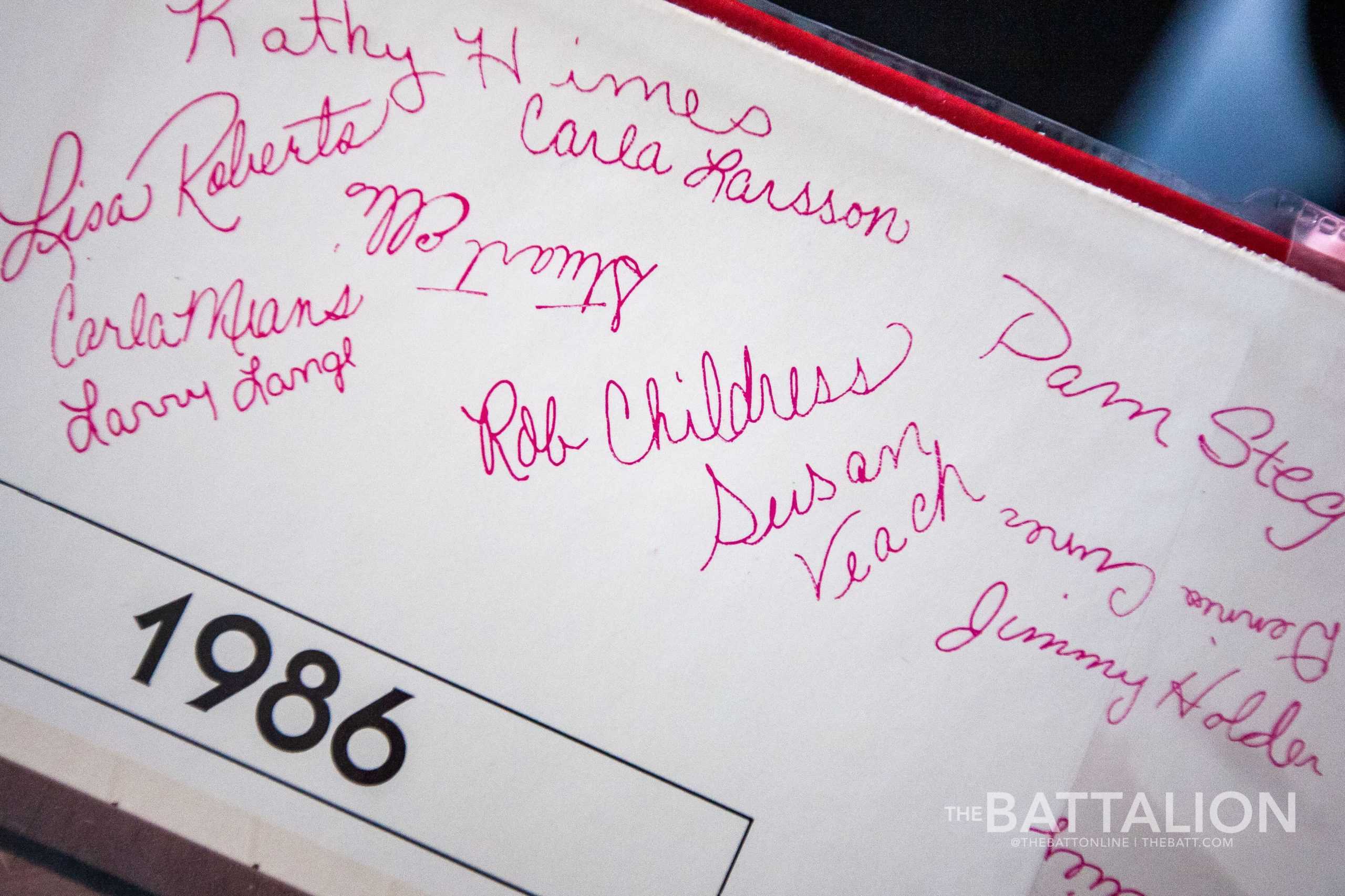

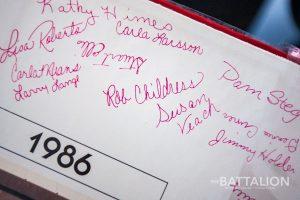

But perhaps the biggest influence Marrs has had on Childress is in his personal life. Marrs played a part in Childress’ nearly 27-year marriage to his wife, Amanda, Class of 1992.

The two met in 1988 while she was a freshman at Texas Christian University. When Childress decided to propose, he needed someone to co-sign for the engagement ring, and there was no doubt in his mind who that would be.

“[Marrs] was the one guy that could do that,” Childress said.

It was at that point that Marrs saw their relationship start to shift as the gesture was a sign of Childress’ complete respect for his high school coach.

“I said that would be my honor,” Marrs said. “Of course, I did tell him he better not miss one payment or I’d kick his butt, and he didn’t. At that point, I think our relationship kind of changed. I became more of a father figure to him rather than just a coach.”

Marrs’ immediate willingness to help Childress is a testament to what those two guys mean to each other, Amanda said.

“It means the world because, for one thing, it wasn’t a matter of if he would co-sign, but when Rob needed him to co-sign, there was no question,” Amanda said. “He would do anything for Rob.”

‘Right time, right place’

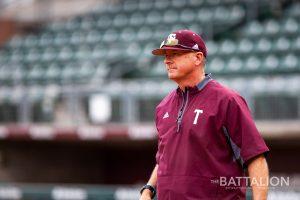

Childress is entering his 15th year at the helm of the A&M baseball team, and during that span, he has seen 578 wins, 306 losses, 13 consecutive NCAA Tournament appearances, six NCAA Regional titles, two conference championships and two College World Series appearances. But Marrs said the success Childress has seen in his professional life is nothing compared to the family he has built.

“What he’s done coaching doesn’t surprise me,” Marrs said. “I knew that his love for the game and his talent to communicate was beyond most people, but what he’s become as a father and seeing how he’s been with [daughter] Hannah, [son] Max and Amanda, that’s what I’m probably most proud of.”

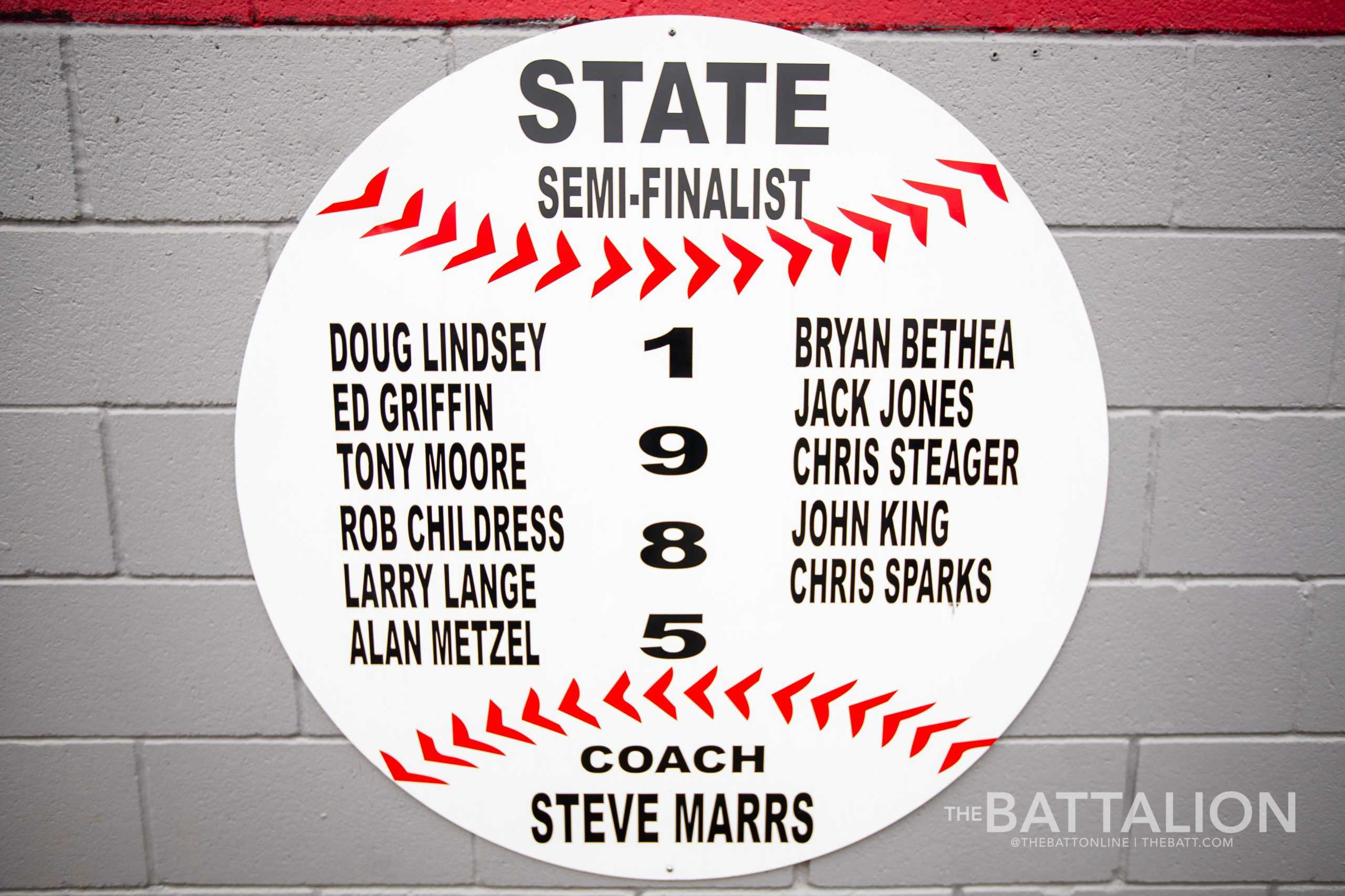

Marrs ended his coaching career after 31 years, with all but three of those spent as a head coach. In his time, his teams saw 496 wins, 206 losses and two ties. His 1985 squad at Harmony, with Childress on the mound, advanced to the semifinals of the UIL State Tournament before a 10-1 loss to Kaufer High School in Riviera.

After six years at Harmony, Marrs coached at Gilmer for nine years, Harleton for three years, Hughes Springs for two years, Gladewater for four years and Pine Tree for four years. He also spent three years as the athletic director of East Texas Christian School in Longview.

“He should be in the Hall of Fame, but I don’t know that he will because he hasn’t won enough games because he hasn’t coached long enough because he doesn’t need to,” Childress said.

Instead, Marrs’ legacy will always be the relationships he forged off the field.

“He has been a father to so many,” Childress said. “He’s certainly been a guy who’s changed my life on and off the field, and I’ve always wanted to be like him in that respect as a husband, as a father, as a friend.

“He without a doubt is the most important male figure in my life.”

It was a relationship built by situations that seemed purely coincidental.

But it is also a relationship that means the world to both men, and Childress always reaches out to Marrs whenever anything exciting in baseball happens.

When Childress was hired at A&M in 2005, he sent Marrs a thank you gift that sits on a shelf in his former coach’s office alongside the autographed baseballs he has collected over the years.

Marrs said, “He may not even remember this, but he sent me a little book called ‘Coach,’ and in the front of it he wrote,

“‘Coach Marrs, you’ll never know the influence you had on my life. Everything that I am and everything that I do is because of you. I just hope that I’m able to influence lives the way you influenced mine. Thanks, Rob.’”

Harmony by happenstance

February 19, 2020

Photo by Photo by Meredith Seaver

Steve Marrs was Rob Childress’ high school baseball coach.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover