The Class of 1967 will return to Aggieland this weekend to commemorate 50 years since their time as students, and to say “Here” for the members of their class who will be called during this year’s Muster Roll Call.

Mickey Batsell, one of the class agents for the Class of 1967, said Eddie Davis Jr. is the first from his class to speak at campus Muster.

“The speaker for the campus Muster is Dr. Ed Davis, who is a classmate of ours, and he was the past head of the A&M Foundation,” Batsell said. “It’s pretty unique, since this is the first time a member of the 50th class has been the Muster speaker.”

Batsell said the new and improved Aggieland is significantly different from the campus the Class of 1967 once knew.

“For many of my classmates, it will be the first time that they’ve been back to A&M in a very long time,” Batsell said. “It’s going to be a real eye-opener to them about all the construction and progress, and just the size of the school.”

Progress seems to be this year’s unspoken theme for the 50-year reunion. According to Batsell, monumental changes were made to the university during his time as a student, including changes to admission standards which allowed both women and African Americans to attend Texas A&M, as well as dynamic changes to the Corps.

“While we were there, our sophomore year, which was 1964 to 65, there were four major changes that took place at A&M,” Batsell said. “Any one of these changes would have been kind of upsetting the apple cart if they took place at other schools.”

Terrell Mullins, a 1967 class agent, said back then, the atmosphere at A&M demanded change.

“The school was not growing; in fact, as I recall, about one-third or a little over of my freshman class had quit by mid-semester of the first semester,” Mullins said. “Earl Rudder had the foresight to make some tough decisions, and I can only imagine the heat he was getting from the alumni.”

The biggest change was making the Corps of Cadets non-compulsory. According to Batsell, the change also opened up many opportunities within the Corps for upperclassmen.

“There were some people that stayed for their third and fourth year that didn’t want to go in the military, so they became what’s called Drill and Ceremony — we call them D&C Cadets,” Batsell said. “They didn’t take the ROTC classes, they didn’t have to go to summer camp, they weren’t under contract, and they weren’t receiving any kind of an allowance from the military branches.”

In accordance with that, there were also some other changes made to the university to help it expand further.

“The second thing that happened was that they changed the name from the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas to Texas A&M University, and that was dramatic,” Batsell said.

Changing the name to something broader helped invite people to the university who otherwise would have been thrown off by the major-related specificity of the previous name, again promoting growth, said Batsell.

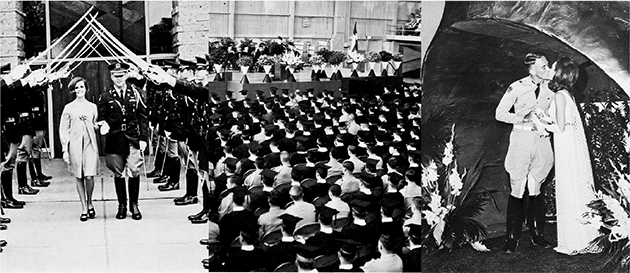

“The third thing that happened was they admitted women to A&M. Not to the Corps, but to A&M,” Batsell said.

According to Mullins, though, this was one change that the university hadn’t been prepared for, mostly because of the way it was before 1964, when the change occurred.

“In 1963, I think what happened was there was very limited allowance for enrollment of females. I think it was wives of Aggies, maybe daughters of faculty members,” Mullins said. “Of course, in those days, there was hardly any place to live other than the male dorms.”

Batsell said the decision to admit women into the college was extremely controversial.

“The Aggieland for ‘64, in the back, the second to last page in The Aggieland, there is a picture of the twelve women that were in that first class that was admitted,” Batsell said. “Their pictures are in the shape of a question mark, so that was kind of an editorial comment by the folks that put together The Aggieland.”

At that time, the university also admitted African Americans for the first time, according to Batsell.

“All of those things took place our sophomore year at A&M,” Batsell said. “Pretty dramatic stuff to take place while you’re a student there.”

But the Class of 1967’s time at A&M was not all drama and serious change in school policy. Mullins recalls some light and some dark moments from his time at A&M.

“While Bonfire was being worked on, Kennedy was assassinated,” Mullins said. “It was decided that in memory of the president, we would not have a Bonfire that year.”

Mullins was a freshman in 1963 — the year J.F.K was assassinated. He and the Class of 1967 didn’t see a Bonfire until their sophomore years.

“As far as our class, I guess we’re kind of known for swiping five Southwest Conference mascots. I don’t know that that’s a great accomplishment that we should be proud of.” Mullins said. “We had to make our own entertainment in those days, there was not much going on.”

However, there is a lot going on now, Batsell said. Muster, for the university, is not all about reminiscing — especially with such a special 50th anniversary class coming back to campus.

“The Muster organizing committee, the people that work on this, they start working on next year’s Muster right after Muster is over,” Batsell said.

The significance of Muster also radiates beyond the A&M campus. Kathryn Greenwade, Class of 1988 and vice president of the Association of Former Students, said the significance of Muster spans the globe.

“You have the campus Muster, which is the largest Muster, but in addition to that, there will be about three hundred Musters that will take place around the world,” Greenwade said. “Some of those will be gatherings of just a small group of people, some of those will be a gathering of several hundred people.”