On Nov. 17, 1999, J.P. Beato III had just finished a volleyball photo assignment for The Battalion. He was tired, but Beato recalled making plans to stargaze with friends. Around 2:30 a.m. on Nov. 18, the group was saying their goodbyes around Beato’s car behind the Reed McDonald Building on the A&M campus. Their conversation ended at 2:42 a.m.

“We heard the crash,” Beato said. “Immediately, it was like, ‘Oh, the only thing that’s going on on campus is Bonfire.’”

Beato said he and his roommate, another student photographer, got in their cars and drove to the site.

“He took one end, I took the other end, [we] parked our cars randomly and started running into the center of Bonfire, as most people [were] running away,” Beato said. “When I was shooting it, it was just, ‘Shoot, shoot, shoot,’ as I’m running in. Everything is chaos. I think the general plan was, ‘Hey, let’s meet in the center.’ That was the start of it.”

The Battalion staff scrapped the front page of that morning’s edition and rewrote the paper to include coverage of the tragedy, Beato said. His photo of Tim Kerlee, the last person to die in the collapse, was used on the new front page. Many people thought the immediate coverage was in poor taste, which was made apparent to Beato and The Battalion’s editorial staff. Other photojournalists, including colleagues of Beato’s, were treated with animosity.

“This is definitely a Bonfire picture,” Beato said. “This is what it was like at the time, so I’ve always been proud of it. How it ages, I think, is up to the individual person who looks at it and has an opinion about it. I’ve always thought it was a great photojournalistic photo.”

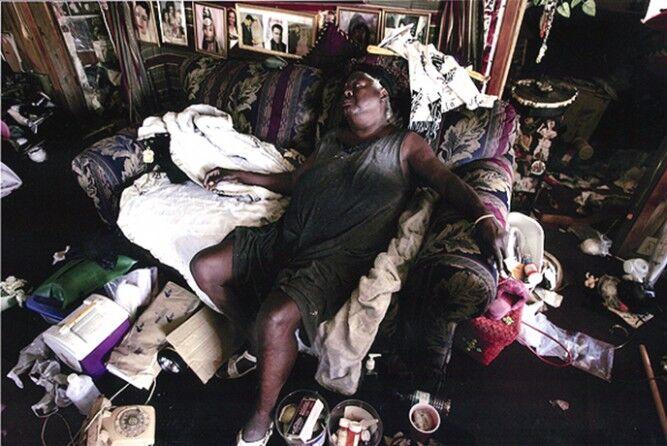

A person in crisis, possibly the lowest moment of their life, looks to see a photographer taking their picture. What is that person feeling? Photojournalists often have little time to wonder.

Balancing empathy, technology and professionalism can be an immense challenge, especially when working on a deadline. Photojournalism has a long history, and the industry’s definition of ethics has changed over the decades. What people see in media is in greater consideration than ever, and 24-hour journalism bears a major responsibility.

BEST PRACTICES

Minimally editing and never staging photos is, and remains, a major priority for photojournalism. Michael Mulvey is an adjunct professor of art, journalism, photography and art history at the University of North Texas. Mulvey is also a former staff photographer for The Dallas Morning News and won the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography in 2006 for team coverage of Hurricane Katrina the previous year.

In journalism, Mulvey said, photographers should always strive to be observers — nothing more.

“There’s no fixing it after the fact,” Mulvey said. “There’s no fixing it while you’re making it. You really are a witness.”

Journalism is a no-excuses industry, when run correctly, Mulvey added. There is no choice but to play by the rules and adhere to the best practices of the business.

“The minute we start making excuses is the minute we get questioned,” Mulvey said.

Tom Burton, former director of photography/video for the Orlando Sentinel and associate professor of the practice and interim director of journalism at A&M, said best practices are always under consideration.

During his time at the Orlando Sentinel, a photographer was covering a base jumper, Burton said. The jumper was going to leap off a cell phone tower located on private property, and entered through a hole cut in the perimeter fence. The photographer followed him and took photos.

“We decided that we shouldn’t use any of those pictures because the photographer would have trespassed also,” Burton said. “That was not best practices in the field. They didn’t call back and ask, ‘Hey, should I do this?’”

THE GREATER GOOD

Modern discussions about photojournalism ethics have a newfound focus on empathy. Marie D. De Jesús, staff photographer at the Houston Chronicle and president of the National Press Photographers Association, is always focused on empathizing with the people in her photos.

“When I started 15 years ago, I think the instruction I got was, ‘Do not make things up,’” De Jesús said. “That bigger dialogue? We were not having it. It was very basic. ‘Don’t fabricate. Don’t Photoshop.’ Those were the conversations; ‘Don’t move things.’ And now we know that ethics is just bigger than that.”

Keeping in touch with her humanity is of great importance, De Jesús said.

“I need to be able to live with myself,” De Jesús said. “I need to be able to sleep at night. I need to be able to minimize harm. I need to know that I have done everything I can to minimize harm. I can’t be part of the trauma.”

On the morning of Nov. 18, the seriousness of the Bonfire collapse came to Beato the moment he saw white sheets over students — the bodies of victims, he said. Beato called Sallie Turner and Marium Mohiuddin, the 1999 editor-in-chief and managing editor of The Battalion, respectively, and told them where he was. They asked what he needed.

“‘I need a runner to find me, I need batteries, I need film, I need them to take my film, run it back to The Battalion office,’” Beato said. “‘I need them to develop this stuff and bring it back to me.’”

His requests were met. While continuing to shoot, contact sheets were brought to him, which he would mark in the field, Beato said. For three straight days, Beato remained on-site to document the collapse. In addition to transporting film, runners brought Beato food at meal times. After he had someone move his car, Beato would sleep in it for short intervals before returning to work.

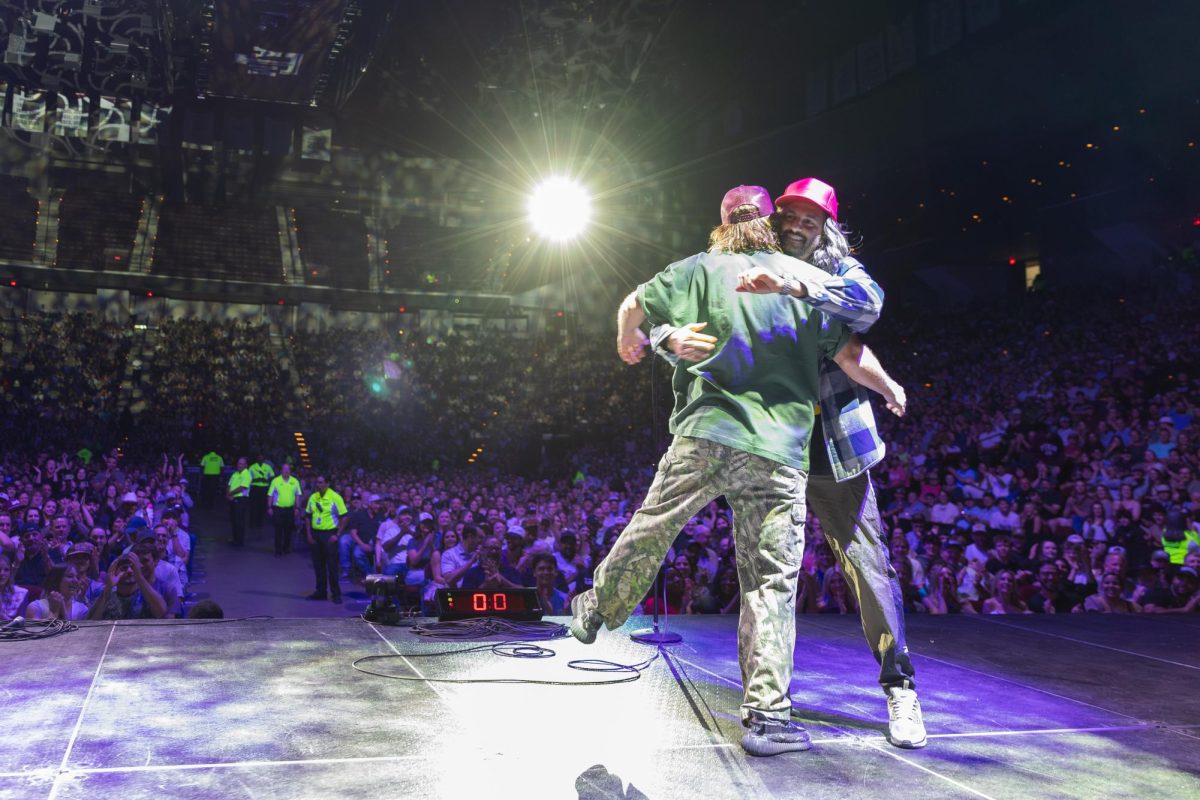

“It felt like all the things I shot for The Battalion before had led up to this,” Beato said. “As the sunrise came up, people were coming to the Bonfire site to see how they could help. People were volunteering to move logs. That’s when the football team showed up to try and help. I’m there documenting as much as I can. Everything.”

Burton said that emotionally challenging assignments require a photographer to know how to approach trauma in a respectful manner.

“It really doesn’t have to do with legal access, sometimes it’s not even a moral question,” Burton said. “It’s just the fact that you’re talking with people or witnessing things firsthand that are just terrible things.”

In the summer of 1982, Burton was an intern for the Orlando Sentinel. During the July 4 weekend, a man held his girlfriend’s children hostage. He didn’t threaten the children but wielded a handgun and acted erratically. He had thrown their mother out of the house before police arrived on the scene.

“When they went into the house, the sheriff had already told them, myself and a TV photographer what was going to happen,” Burton said. “The angle we had, there was a car between us and the front door, so when the cops went in the door, I ran sideways into an empty lot to get an angle. I heard gunfire. ‘Pop, pop, pop,’ and the cops ran out of the house.”

Burton laid on the ground, readied his camera, and watched as the man stepped through the front door. The man fired at a deputy, which prompted a sniper to fire in response.

“I have two frames — the last two seconds he was alive and the first two seconds he was dead — and it freaked me out,” Burton said. “Ran on the front page.”

The children were rescued, and a photo of them ran in the same paper. It’s arguable whether the photo should have run or not, Burton added.

“We had fewer discussions like that in the [1980]s,” Burton said. “Those are more ethical, ‘Does it serve the greater good?’ kind of things.”

At the Houston Chronicle, the greater good of the readership is always their top consideration, De Jesús said.

“There is an expectation that if you work here, you understand the location that we are in,” De Jesús said. “The state, the proximity to the border, the type of situations in terms of natural disasters that happen here.”

There is no tolerance for recklessness at the Chronicle, De Jesús said.

“I’m telling you, they will not hire folks that don’t respect the community,” De Jesús said. “It’s not the way that we work here.”

Photographers, like reporters, need to approach every story with research and context, De Jesús said. Education and empathy are critical to speaking with people, especially if their experience differs in terms of upbringing and culture.

“Having in your staff people that have lived with themselves, in their own skin, is key,” De Jesús said. “When you come from other backgrounds, there’s things that come completely automatic, because you have seen it, because you have experienced it.”

Growing up in Puerto Rico, De Jesús said she lived through severe hurricanes and tropical storms. She’s seen how storms affect education, household stability, marriages and family life. She understands what it’s like to spend months without electricity and water. Most photojournalists can’t relate to that experience, but they can still approach their stories with honesty and compassion.

“People know when you’re not being genuine, and when you’re trying to trick them,” De Jesús said. “Go prepared, be sensitive, be empathetic. There’s things that will take a little bit more research, but there’s other things that are — or should be — common sense.”

DISTANCE

The eye movements of 52 readers were tracked as they read newspaper and website front pages in a 2015 study by the NPPA. Out of 200 photographs of varying quality, six photos were discussed in the NPPA’s follow-up. The study found that readers were more engaged with photos that told a story, were unposed and showed the reality of a situation

The above image, taken by Al Diaz of the Miami Herald, shows a baby receiving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation from paramedics on the side of a highway. From an unobtrusive distance, Diaz used a telephoto lens to take the picture, which was published in the Miami Herald. The family was glad the photos were taken, Burton said, because it showed that people were willing to help their baby.

Though a short distance is typically sought after in journalism, tools can be used to take photos from a long distance. This is ideal for situations where access is limited, or when professionals need to work without obstacles.

While photographing the aftermath of the Bonfire collapse, Beato said he used a 300mm lens and a teleconverter. For a 9-foot-tall field of view, a 300mm lens can reach a full frame distance of 144 feet, according to figures from Lensrentals and Digital Camera World. When used together, Beato could reach a minimum full frame distance of 201.6 feet. This meant that Beato didn’t have to be close to get photos of the collapse. He could be out of the way and still get coverage.

“I felt like that was key in getting some of these images, because I wasn’t right up there,” Beato said. “I wasn’t shooting with a wide, so I wasn’t close. Just documenting from afar.”

PHOTO EDITING

As digital photography and editing software has become widely used in photojournalism, the tolerance of photo editing has similarly expanded, Mulvey said.

“Not only that, but it’s a horrible thing, because it doesn’t work well with deadlines,” Mulvey said. “You’re already dealing with a smaller staff, a smaller group of photo editors, copy editors — editors in general — that are putting out this product. Then something is arriving in that space. Quite frankly, is there enough time to even question that?”

Photo editing software has become a major part of training in the digital age of photojournalism. Fixation on the editing process has been a major crutch for some photographers, Mulvey said.

“How do you tell someone that they don’t need to do that?” Mulvey asked. “You don’t want to be a curmudgeon to technology. You don’t want to be like whoever the last person was, who said they should be shooting film and not digital. No one’s listening to that person anymore.”

Photo editing doesn’t invalidate photojournalism, Burton said.

“As a journalist, your role is to depict accurately and fairly what was there,” Burton said. “Whatever I do in toning is to represent that, and at times to accommodate the limitations of the capture process. Film is a very limited capture of what we see.”

Printing photos captured on film can lead to a detrimental loss of detail, Burton said. In a digital capture, details lost in shadows can be brought back in the editing process, and the reality of the moment can be better represented. When the image becomes unnatural, painterly or its content has been altered, then it is no longer ethical to use.

“Society at large is much more aware of what you can do to be — if not outright lying — at least misleading with photography,” Burton said. “‘A photo doesn’t lie’ was a phrase that used to be pretty close to being unquestioned. I never hear anyone say that anymore.”

CHANGES TO THE INDUSTRY

Reporters sent to foreign countries to cover international incidents are referred to as “parachute journalists,” Burton said. In the 1980s, the photographers the Orlando Sentinel sent were often the best in the country, since the skill was not commonly taught outside of North America or Western Europe, nor was there a way to transmit photos.

Parachute journalism exists today, and can still be necessary at times, Burton said. Photography is now more common and accessible worldwide, and almost anybody can teach themselves to use a camera. This change has highlighted the needless risks of parachute reporting, such as influencer Ryan Fila’s amateur attempt to cover the conflict in Ukraine.

“The problem with Ukraine is that it’s a war, and you can get hurt or killed, but more importantly, your presence there endangers other people,” Burton said. “[You are] just simply a distraction. I go there, I get shot, somebody might have to try to save me, who puts themselves into danger unnecessarily, because I happen to be there.”

Pay and opportunities for work have also changed throughout the years, Mulvey said. For example, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the reporters who broke the Watergate scandal, worked in a very different landscape.

“Starting at about 1975, they are the two journalists making six figures,” Mulvey said. “They never stopped making that money, and they make seven figures now or more. That’s not available to everybody. However hungry and unfortunate their moves into journalism were in 1970 — let’s face it, they could still buy a car, they could still pay their student loans and they never really thought they might not have a house. It’s not the same environment.”

Mulvey, who interned at The Boston Globe in 1992, said he can see a steep difference in pay compared to today’s industry.

“Thirty years have gone by, and that amount of money has gone down,” Mulvey said. “I didn’t feel like I was rich in 1992. I feel like everything went to cameras, or housing or my car. It’s harder now, right? That should be, probably, at least $1,000 a week, and it’s not.”

The lack of investment in newsroom photographers causes many photojournalists to freelance, which can add further strain to their workload, Mulvey added.

“We shouldn’t have staff photographers working side hustles, just like you shouldn’t have teachers driving Ubers,” Mulvey said. “Like, on a double-header baseball game, to be working for one publication and work for another publication. What if something happens at that event? Am I now beholden to one over the other? It’s a really strange place to be.”

Immediate coverage of tragedies is more common today and accepted as part of mainstream media, Beato said. The Battalion’s coverage of the Bonfire collapse predated that change, and backlash was accelerated by the graphic nature of the imagery. Despite the public’s disdain, Beato was never criticized by other news organizations or A&M administration.

“I was never told not to do anything with that photo,” Beato said. “I have never directly talked to Kerlee’s parents about that photo. I don’t want to speculate on what they thought, but I assumed that it’s probably not the greatest thing for them to look at.”

During his time at The Battalion, Beato said he would cover anything related to Bonfire.

“All the way through, to continue the story,” Beato said. “All the campus vigils, all the Silver Taps-related things. Anything that had to do with that. Even when they had the hearings about it, I would show up and shoot.”

The tragedy has loomed over A&M ever since, Beato said. 23 years later, Nov. 18 remains an important date in Beato’s life.

“It comes up every year,” Beato said. “They still have the vigils and gatherings out at the Bonfire site. It’s in my calendar, I’m always reminded that that date’s coming up. I’m constantly aware of it.”

AWARDS AND CONTESTS

Contests, rather than the ever-shrinking photography staff in newsrooms, have become incredibly stringent when it comes to the ethical standards of photojournalism, Mulvey said.

“I think that’s where the gatekeepers are,” Mulvey said. “Everyone wants to win awards. Everyone wants to know who’s the best. Then you have big leadership in terms of [The] New York Times, or [The] Washington Post or [The] Associated Press. They need to be the ones that are being the leaders.”

While she doesn’t speak for newsrooms around the country, the Houston Chronicle submits to contests based on professionalism and a strict adherence to the NPPA code of ethics, De Jesús said.

“We don’t work based on contests,” De Jesús said. “We’re based on what our readers and our own ethics expects and requires of us.”

THE INDUSTRY’S NEXT STEPS AND LEADERSHIP

Leadership can return to the newsroom, and photojournalists can re-energize their photo departments, De Jesús said. It comes from working within and teaching towards communication skills.

“As we create, and as we develop the next generation of visual leaders, we need to teach them how to work well with the expectations of upper management while also being faithful to our mission as photojournalists,” De Jesús said. “If we don’t make those steps in developing this talent, in helping photographers transitioning to management and leadership, we’re going to confront issues in the future.”

To avoid the loss of photographers in the industry, visual literacy needs to be taught to upper management positions in journalism, De Jesús said.

“I feel that they are not always fully connected to what we do and the importance of what we do,” De Jesús said. “Visual leaders that were photographers in the past and now are in management, that would be key. People that can communicate well. That can communicate well our mission and who we are. That’s key. People that can connect across the aisle with other desks — you need to be able to have healthy relationships with other departments, so you can push your department forward.”

The journalism profession is directly tied to “making-money endeavors,” Mulvey said, and perhaps some news organizations should be regulated to preserve the effectiveness of the industry.

During the last four months of 2020, 13.9 million monthly visitors went to the top 50 U.S. daily newspaper websites, an increase of 14% from 2019, according to a 2021 study conducted by the Pew Research Center. However, average time spent on each website decreased from 2.1 minutes to 1.82 minutes from 2019 to 2020. In other words, the Pew Research Center found more people see the news, but spend less time absorbing it.

“You can’t have a functioning democracy without good journalism,” Mulvey said. “It’s just being attacked from every angle. I think maybe that’s part of the point. Maybe people just don’t want to know the truth.”

Mulvey said that despite photojournalism’s current roadblocks, it’s still a valuable profession. He equates its necessity to cameras on police officers or in doorbells – people are deeply invested in digital surveillance and visual reporting.

Having the conversation is the first, and most crucial, step, De Jesús said, as is recognizing the industry successes and faults as it moves forward.

“Ethics is a topic that we could be here all day, because it’s not just that it’s important, it’s a very complicated topic,” De Jesús said. “I don’t think that we will ever fully agree as an industry on some things.”

Improving the dialogue between journalists and their communities is another necessary step toward the future, De Jesús said.

Beato is now a professional photographer and multimedia manager at A&M. His coverage of the Bonfire aftermath inspired him to pursue photography as a career, though not in journalism, Beato said. He still feels pride in his coverage, and continues to match that satisfaction in his current work.

“I feel like it was a big event for The Battalion,” Beato said. “I feel like The Battalion covered it in the best way possible, given our resources and given that we were contributing to everything else, to all the other news organizations that needed help.”

While publications in the industry work well together, they have a delicate relationship with their readers, De Jesús said.

“Journalism is going through a moment in which the public is not fully trusting,” De Jesús said. “How do we repair those relationships? It’s key. How do we get them to trust us? It’s an ongoing question. Not just the trust from one specific group but from different [groups] who understand our role differently. You see, it’s more questions than answers at the moment. I feel that the right thing is to have those dialogues, have an open mind and listen.”

Cameron Johnson, Class of 2022, contributed this piece from the course JOUR 490, Journalism as a Profession, to The Battalion.