Flowing throughout Aggieland, there’s an almost-mystical aura of legend and strength which fills the air. It’s like a mist, ebbing and swirling to reach every crevice of the Texas A&M campus.

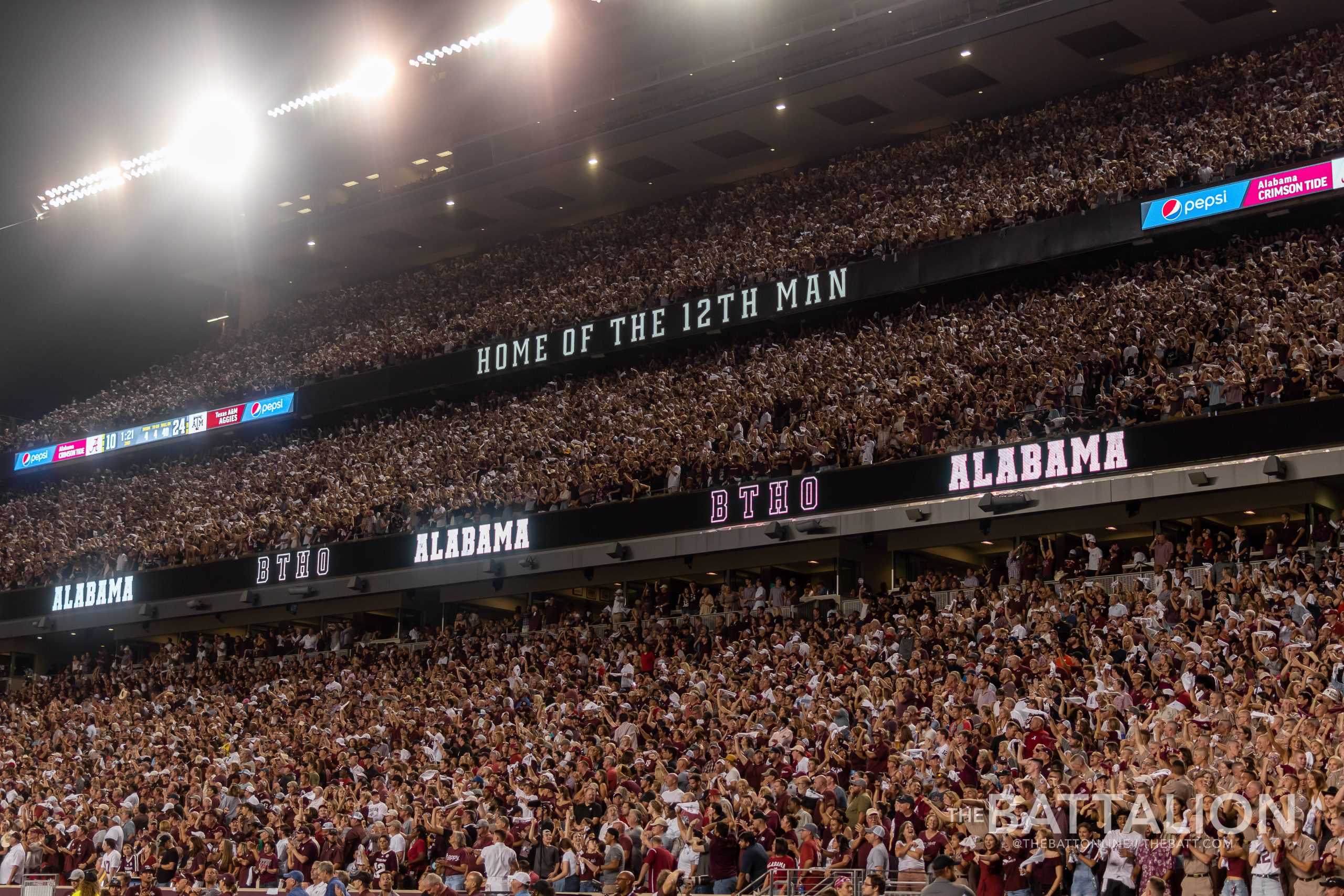

This force fills many roles at A&M. It’s what drives students to camp out for over 72 hours to get front-row tickets to watch the Aggies host the No. 1 Crimson Tide, just minutes after the maroon and white fell to an unranked opponent, among countless other influences.

A fable in and of itself, the myth goes by many names. The embodiment of school pride. The lifeline of campus. The Spirit that can ne’er be told. But above all else, this figurehead of maroon and white folklore goes by one iconic name: the 12th Man.

Serving as a symbol of unity and commitment across campus, the 12th Man has taken many forms over the last century. Its history is complex, and regardless of the highs or lows through which the ideal has traversed, it has become an undeniable, irremovable aspect of campus culture representative of all fronts of the university as a whole — the joyful, the crude, the endearing, the revolutionary and the ugly.

Beginning of an era

At the end of the 1921 regular football season, the Aggies were on top of the world. A 5-1-2 record, including a 3-0-2 resume in conference play, was enough to earn the maroon and white the title of Southwest Conference champion. To reach that point, A&M remained undefeated in the SWC and took down the Baylor Bears, 14-3, in the Battle of the Brazos.

But before the Aggies could breathe long enough to celebrate, they had to overcome their biggest obstacle yet — the Centre College Praying Colonels.

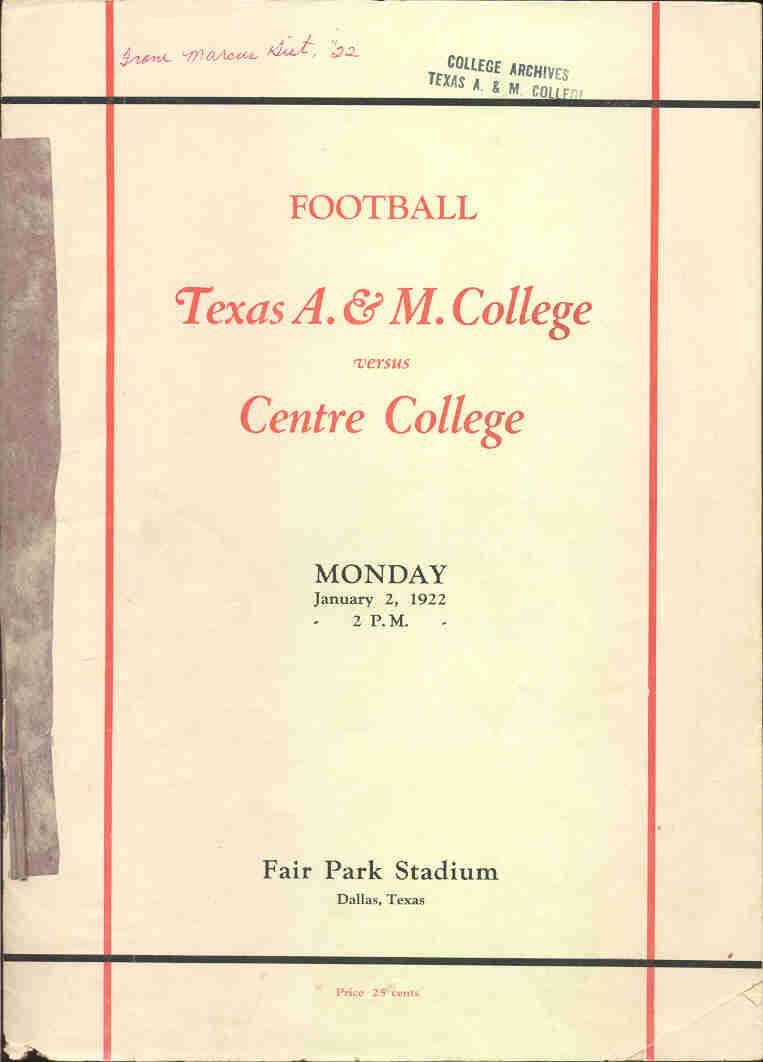

When it was announced the two teams would play each other in the 1922 Dixie Classic, held on Jan. 2 at Fair Park Stadium in Dallas, A&M fans were unsure how to feel. Going into the matchup, Centre had maintained a perfect 10-0 record, outscoring its opposition 314-6. Compared to the challenge in its way, the maroon and white’s regular season schedule had been a cakewalk.

Though A&M entered the game’s halftime break with a 2-0 lead thanks to a fluke safety on a Centre punt return, it was not without cost. A large portion of the Aggies’ starting roster, including team captain and running back Heinie Weir, had been removed from the game due to injuries caused by the undefeated team’s ferocious playing style. With available players further dwindling with every play run, A&M head coach and eventual College Football Hall of Fame inductee Dana X. Bible did something unheard of: He signaled to a man in the stands to come down onto the field, change into Weir’s uniform and stand on the sidelines as a potential substitute if necessary.

The man in question was none other than E. King Gill. By this point, Gill had already made a name for himself on A&M’s campus. As a freshman, he stunned the university with his athletic prowess in both basketball and baseball, both of which he would go on to letter in while at A&M. Gill even began the year on A&M football’s reserve team before leaving to focus on basketball. As such, Bible likely had no doubt about the dual-athlete’s ability to compete in the Dixie Classic.

So, Gill did what he was asked. He left the press box, where he was assisting sports reporters by identifying players in the game, and marched down to the field. After changing into Weir’s jersey under the bleachers, Gill stood on the sideline, ready to play at a moment’s notice.

“Boy, it doesn’t look like I’m going to have enough players to finish the game,” Bible said to Gill, according to an interview with the Houston Post in 1971. “You may have to go in there and stand around for a while.”

Though he never played in A&M’s eventual 22-14 upset over Centre, Gill remained standing attentively — the reported lone uninjured replacement by the end of the game.

“I wish I could say that I went in and ran for the winning touchdown, but I did not,” Gill later said. “I simply stood by in case my team needed me.”

Thus, the legend of the 12th Man was born, and Gill’s commitment to his university is the reason A&M’s student section, now called the 12th Man, remains standing throughout all football and basketball games.

“[Gill’s] willingness to be there and help out his fellow Aggies absolutely exemplifies what it means to be an Aggie,” Kalee Castanon, assistant director of Visitor Experience with A&M’s Enrollment and Academic Services, said. “Not only that, he showed Selfless Service by being there just in case he was needed.”

At least, that’s how the legend goes.

Separating fact from fiction

In actuality, the game’s events were far less idealistic. There is no doubt surrounding Gill’s presence at the Dixie Classic, nor does anyone argue that he was not called to the field by Bible to wear Weir’s jersey and act as a potential substitute. But the similarities end there.

Within the framework of the Dixie Classic’s actual progression of events, Gill’s involvement was less critical than legend suggests. According to December 1921 articles of both The Dallas Morning News and the Houston Post, A&M had a full roster of 25 athletes present at the game.

Based on all published play-by-play accounts of the game, only four Aggies had been pulled due to injury by the time Gill was summoned to the field. Barring one other player’s absence, who was hurt during the team’s pre-game practice, A&M would have had another nine healthy substitutes waiting on the bench to enter the game.

Instead of being the final man standing on the sideline, Gill was likely, at best, the final option at running back, especially considering he was wearing Weir’s number.

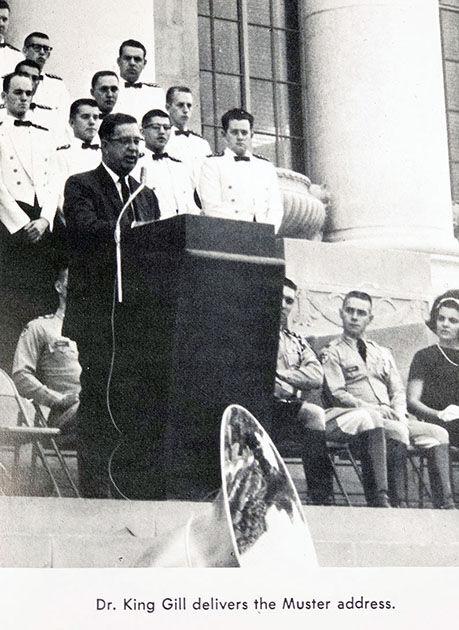

Gill later supported this conclusion. While speaking at the 1964 Aggie Muster, the original 12th Man recounted his time at the Dixie Classic, including the specifics of what players were injured and why he stood on the sidelines.

“We had lost most of our backfield by then,” Gill said in his speech. Though mostly illegible transcripts were discovered some time after, an actual recording did not surface and confirm his statements until 2019.

With this, the flawless facade of the 12th Man was shattered. However, the decision to not focus on this discrepancy was seemingly unimportant, as the tradition enabled the university to grow in an otherwise-unattainable way.

According to Cushing Library curator Anton Duplessis, Class of 2003, the misconstruing of the story was not intentional. Instead, a general miscommunication helped spread the modified story, he said.

“[Gill’s] readiness passed into Aggie lore with a 1939 radio anecdote from [the] Association of Former Students head E.E. McQuillen, Class of 1920, telling the story,” Duplessis said.

Aftermath of the game

Even if only based in half-truth, the legend of the 12th Man had begun spreading its roots throughout the A&M campus and beyond. In the end, the fabled figure garnered far more influence than anyone thought possible.

According to Adam Quisenberry, vice president of Marketing & Communications for the 12th Man Foundation, this is because Gill’s actions provided the opportunity to cultivate “something special” within all members of the A&M community: unity.

“What binds people together once they graduate from A&M? They still want the Aggies to be the best of the best across the board,” Quisenberry said. “That really goes a long way in making sure we have something … that all Aggies can be proud of.”

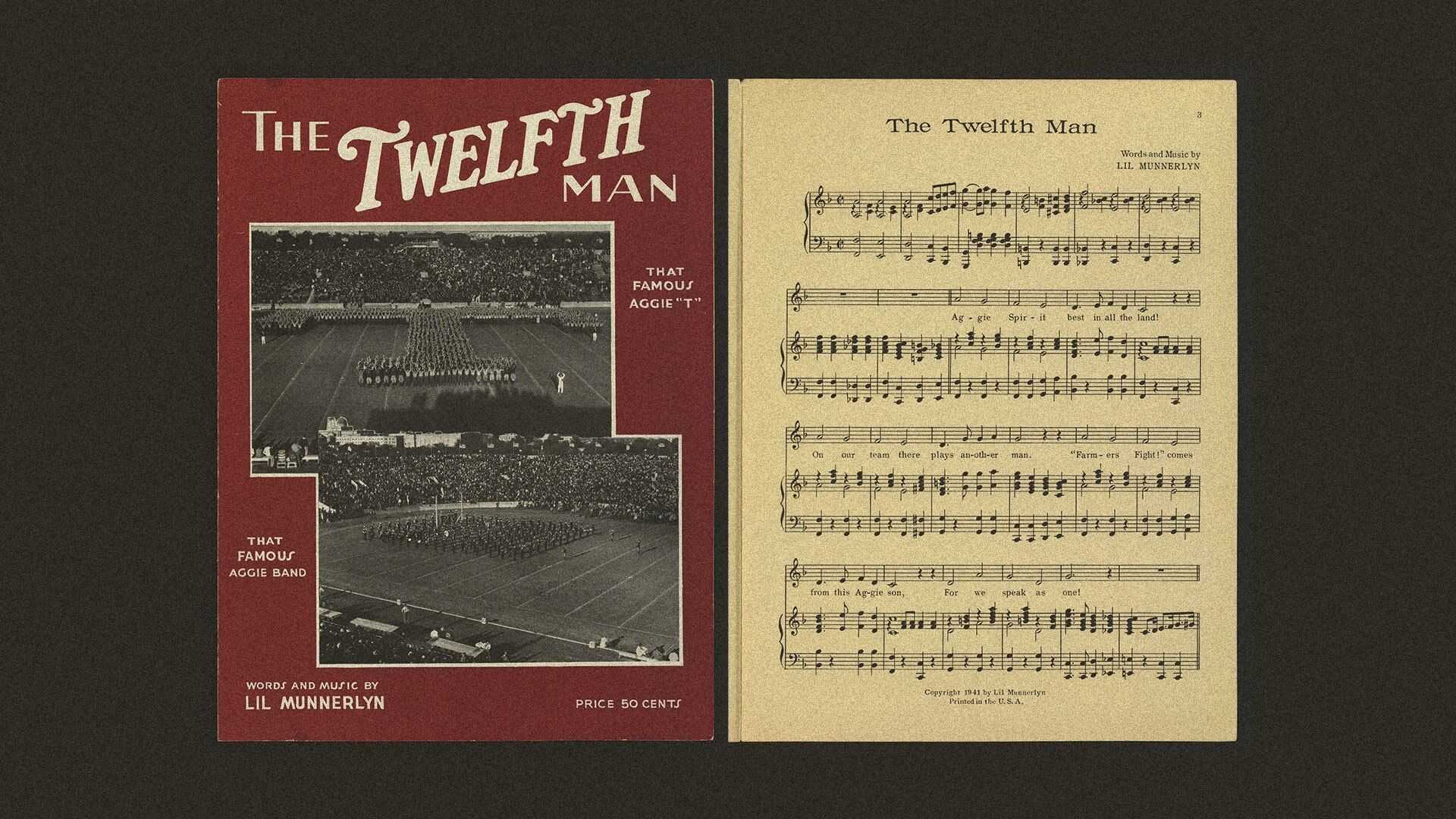

Though Gill was honored as a legend on campus, little else occurred in relation to the 12th Man’s involvement with the athletes themselves. Sure, the Fightin’ Texas Aggie Band spelled out “12th Man” in 1930, “The Twelfth Man” song was written and published by Lil Munnerlyn in 1941 and a banner reading “The Twelfth Man Is Here” debuted in the Kyle Field student section in 1968. But none of these new traditions affected the players’ performances.

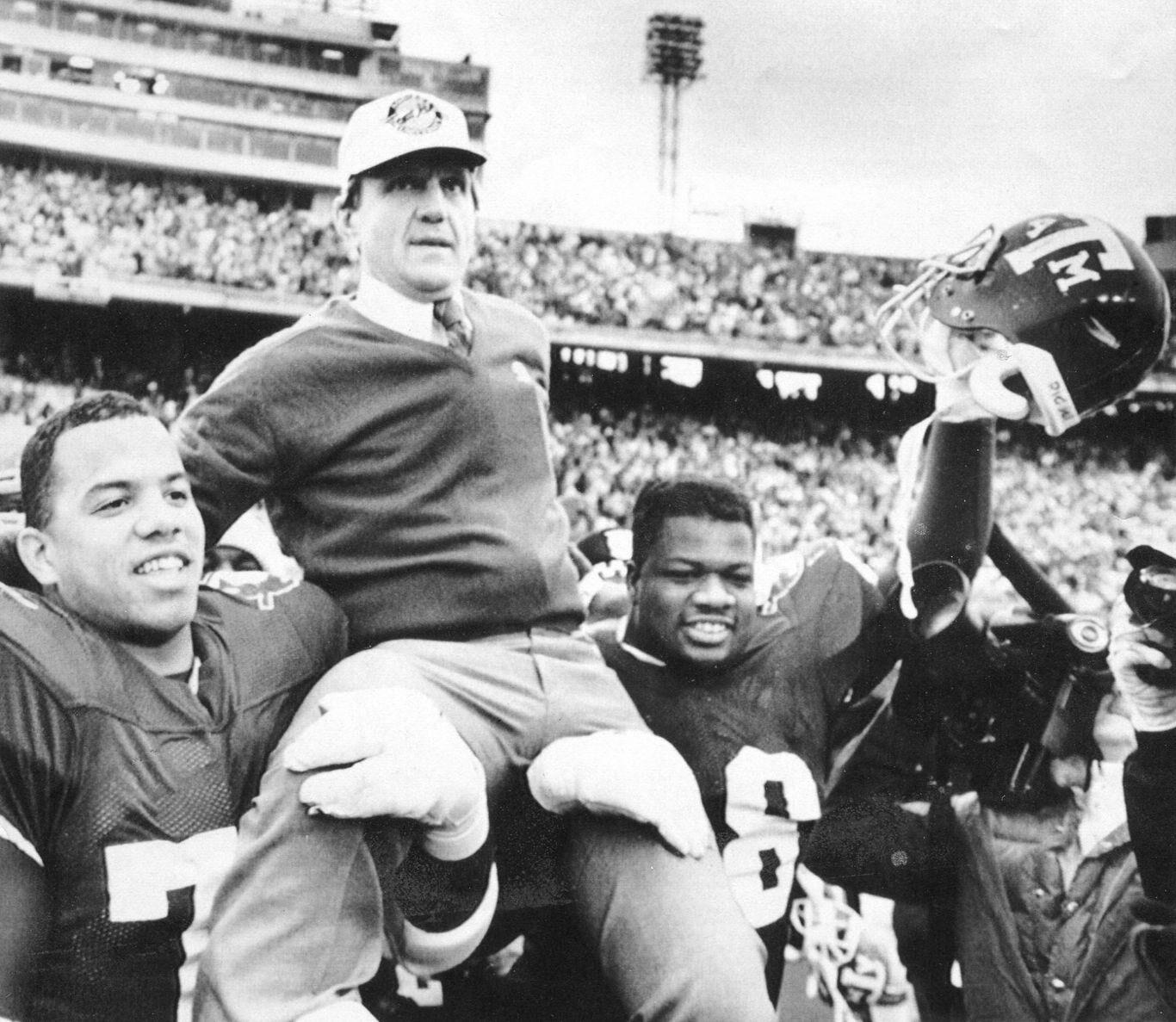

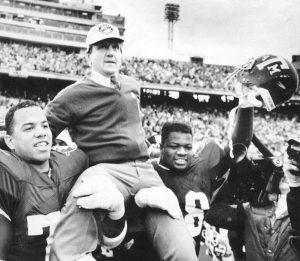

This changed in 1982 when A&M hired Jackie Sherrill as the new head football coach. To honor Gill, Sherrill founded the “12th Man Squad” soon after arriving in Aggieland.

The group — composed entirely of non-scholarship players — acted as the program’s special teams unit. Because these athletes played only on kickoffs, they were often much more willing to make risky or dangerous plays. The players, in turn, collectively became known as “the Suicide Squad.”

After Sherrill’s departure from the program, the founder of the Suicide Squad was succeeded by now-College Football Hall of Fame inductee Richard Copeland “R.C.” Slocum.

Intended to more-accurately embody Gill’s actions at the Dixie Classic, the tradition was changed by Slocum to instead be represented by a sole player. That athlete, wearing the No. 12, would personify the 12th Man during special teams plays.

The inheritor of the legendary number is chosen based on how well someone “represents the university,” current head football coach Jimbo Fisher said in the latest announcement of the most recent successor.

Quisenberry said A&M always having a No. 12 on the field allows Aggies of different ages to connect and find something in common. This sets A&M apart from all other universities across the nation, he said.

“For a lot of the people that support the 12th Man, their passion for Texas A&M Athletics was born during their time on campus, and they’ve carried that spirit with them,” Quisenberry said. “That’s unique to A&M.”

Since Slocum’s change was enacted in the 1990s, a handful of athletes have donned the fabled title, including New York Giants fullback Cullen Gillaspia — the first 12th Man to ever reach the NFL. Gillaspia was also the first 12th Man in program history to score a touchdown, coming in the team’s final offensive play of the 2018 Gator Bowl.

In addition to its prominence on the football field, the tradition of the 12th Man has found influence beyond athletic settings. Now, A&M’s 12th Man Foundation helps “fund scholarships, programs and facilities in support of championship athletics at Texas A&M,” its website reads.

Along with oversight of A&M Athletics’ ticketing and the Champions Council, the Foundation gives awards to donors and other supporters who show extreme commitment to the program. When determining the various distinctions, Quisenberry said there was never a doubt regarding how Gill’s 12th Man would be honored: the E. King Gill award.

“It’s the highest honor that we give out on an annual basis, and it goes to people who have really distinguished themselves in support of the 12th Man,” Quisenberry said. “The people that receive this award are model examples of Selfless Service, giving back and wanting to provide a pathway … toward the future of A&M.”

Today, a statue of Gill proudly stands outside the northeast corner of Kyle Field, and students at all football and basketball games remain standing for the entirety of the matchups.

Controversy

Unfortunately for A&M, nothing is ever truly as good as it seems.

The history of the 12th Man is marred by controversy, including multiple lawsuits both from the university and against it. The disagreements of particular importance stemmed from the likely fact of Gill not being the only healthy player on the sideline during the 1922 Dixie Classic.

Michael Bynum, a sports author and publisher who has long studied the history of A&M, said it is important to consider the aforementioned articles from The Dallas Morning News and the Houston Post as well as the play-by-play statistical recaps kept of the Dixie Classic when looking into the history of the 12th Man.

“You’ve got to listen to the media that was there, in person, physically covering the game,” Bynum said. “They are the single best source of what’s right and wrong.”

Instead, a trademark over the use of “12th Man” in marketing and merchandising was established by A&M in 1990, with claims regarding Gill’s involvement in the Dixie Classic cited as reasoning for why the university deserved trademarking rights. The trademark was later declared incontestable in 1996 after A&M filed a Section 15 Declaration of Incontestability.

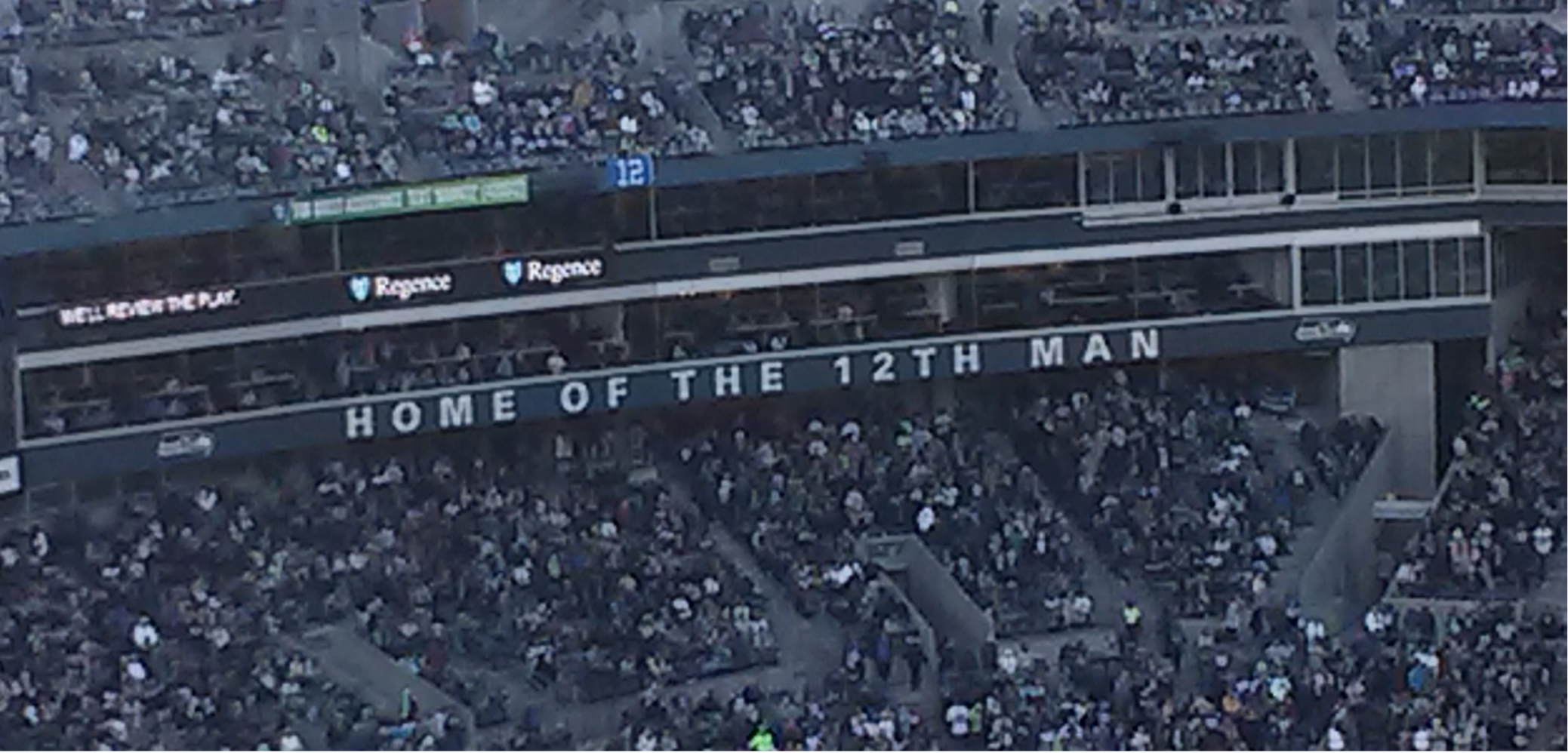

The university had to fight for these rights because, at that point in 1990, the “12th Man” was a blanket term encompassing much of the sports world around the globe. Most notably, the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks retired the No. 12 nearly six years before to honor its fanbase, which had since used the nickname.

As such, Bynum said it was irresponsible of A&M to establish ownership over “something so generic.”

“A&M’s [Office of Brand Development] should not have allowed the university to file for a trademark over the 12th Man in 1989,” Bynum said. “At that time, ‘12th Man’ was used by multiple teams. It was honestly so generic that nobody even realized A&M had gotten the trademark for a long, long time.”

In 2006, A&M sued the Seahawks for trademark infringement. Seattle settled to the tune of $100,000 per year in exchange for the right to continue referencing the 12th Man in official team promotions. The NFL team has since agreed to pay heightened annual fees of $140,000 as part of a new licensing deal beginning in 2016. A&M has profited over $1.5 million since 2006.

A similar situation occurred between A&M and the Indianapolis Colts, but franchise owner Jim Irsay’s organization agreed to stop using the term. The issue was dropped without payment from either side.

Though the Colts avoided any serious issues, Bynum said the Seahawks were unjustly penalized because of misleading phraseology in A&M’s original 1990 trademark.

“Had it not been for the specific [contract] wording of what [A&M] said in 2005, then the Seahawks potentially could have won the case or kept using the terms,” Bynum said. “You’ve got to be pretty brave to face off against an NFL team like that.”

Other lawsuits have since followed, spanning beyond the image of the 12th Man. Bynum himself is currently involved in an ongoing lawsuit originally slated against the 12th Man Foundation, which he claims illegally distributed parts of his copyrighted biographical novel without just compensation.

Even more recently, a class-action lawsuit was filed against the 12th Man Foundation on the grounds of contract breach. As reported by The Battalion in 2018, donors and former students felt their agreements with the Foundation for football gameday seating and parking were disregarded.

According to the Houston Chronicle, over a dozen similar lawsuits were filed against the 12th Man Foundation between 2011 and 2018.

Bynum said it is a set of skewed priorities within the organization which cause this repeated issue.

“Within the Athletics Department, there’s this mentality of, ‘I have to win,’” Bynum said. “And on the field, that’s a good thing. But when it comes to big issues like this, there is an inability to admit mistakes, settle them and move on. That’s some sad commentary, but it is what it is.”

Many cases have been dropped or gone unresolved, largely thanks to A&M’s claims of sovereign immunity, which prevent the university or its subsidiaries from being sued without its consent.

With no clear resolution to these controversies in sight, Bynum said he sincerely hopes A&M will move back toward embodying the Core Values which Gill represented in 1922 and beyond.

“To me, when you shake somebody’s hand and make a deal, you gotta live by it,” Bynum said.

Cultural, social growth

Regardless of rough patches in its history, the 12th Man has persevered.

Scott Waltemyer, a sport management professor in A&M’s College of Education & Human Development, said this success is best analyzed on a sociological level. There are a number of “primary sociological perspectives” which influence both sport institutions within culture and society, he said.

Doing so allowed for the development of a “common identity,” which is a shared sense of belonging within a group, Waltemyer said.

Doctoral student Kathryn Rowe, a young expert in A&M’s Department of Sociology, said institutions outside the world of collegiate athletics were the driving force behind the development of the 12th Man.

“All other institutions that are present in society are also present in sports: gender, race, class and education, among others,” Rowe said. “Rather than treating sports as its own aspect of socialization, it’s better to look at it as a part of a complex network.”

Waltemyer said two sociological perspectives “immediately come to mind” when examining the 12th Man. The first — the functionalist perspective — helps to identify and understand the role or function something performs within a group, Waltemyer said.

At A&M, the 12th Man serves a variety of functions. The most obvious, Waltemyer said, is the way in which the tradition allows Aggies to support each other by giving them common ground on which they can relate to each other; this directly correlates to the university’s Core Value of Loyalty.

Nearly a century ago and less than two years after Gill’s actions at the 1922 Dixie Classic, A&M’s enrollment had just surpassed 2,000 total students for the first time — a stark contrast to today’s student body of 72,982, the second-most populous university in the country. The 12th Man could not have survived in a culture for 100 years without serving a purpose within this functionalism, Waltemyer said.

“The 12th Man contributes to the common identity of Aggies and A&M supporters,” Waltemyer said. “Having something in common — something that bonds people together — comes from a functionalist perspective.”

In that time, campus demographics changed drastically. Women enrolled for the first time at A&M after a 1963 decision by the then-university Board of Directors. This same announcement opened the door for Black students to become Aggies as well. Now, women make up 47.1% of the student population, and various racial minorities represent 42.13% of the make-up, according to university demographic metrics from the fall 2020 semester.

Rowe said this has contributed to an “evolution” of the 12th Man, as the tradition now encompasses a more broad symbolic meaning than it once did.

“Socialization happens quickly, but originally, that construction is only relevant to the people that share that meaning,” Rowe said. “Some things have more permanence, but even that will eventually evolve. At the beginning of A&M history, being an Aggie meant being a white man in the military. Today, the concept of being an Aggie still exists, but the social construction has an entirely different definition [by encompassing minority populations and other once-disregarded groups].”

The other prominent perspective to analyze, Waltemyer said, is that of an interactionist. This examines how interactions and involvement with others influence the interpretations and identities attributed to certain contexts, groups and situations.

In this way, choosing to receive a college education at A&M is the first step toward identifying as part of a lasting group of alumni, which will likely be seen in a positive light throughout a person’s lifetime, Waltemyer said.

“When you become a student at [A&M], you immediately become a part of the 12th Man, and you learn the traditions, the history, the common languages,” Waltemyer said. “Ultimately, that solidifies your identity as an Aggie.”

Because joining the 12th Man is ultimately a lifetime commitment, Rowe said embodying the tradition, from a sociological viewpoint, is an ever-diversifying task.

“The 12th Man is a concept that’s made by people at Texas A&M, and that can be something that’s different based on historical facts, so you might find that the idea of what it means to be the 12th Man changes as the university grows,” Rowe said.

Therefore, at its core, the adoption and subsequent growth of the 12th Man has become a psychological and sociological phenomenon. As such, many implicative factors are intangible, but its growth is undeniable nonetheless.

This allowed the tradition of the 12th Man to become synonymous with A&M as a university, as Gill’s legacy — and the fans who support the tradition — are recognizable on a national scale, Waltemyer said.

“The longer an idea is a permanent part of a group, the stronger, more embedded and more entrenched it becomes within that culture,” Waltemyer said. “The 12th Man has been around for 100 years, so it hasn’t been adopted by only a small percentage of Aggies. It’s honestly a part of our entire, university-wide institution.”

100 years later

With this “university-wide” development came a newfound sense of modernity, as A&M is now supported by the 12th Man of today.

“The power of the 12th Man is echoed in the unity, the loyalty and the willingness of Aggies to serve when called to do so,” A&M’s website reads. “It is the reason that Texas A&M has earned a name that embraces Gill’s simple gesture of service: Home of the 12th Man.”

The 12th Man essentially became a standard in college football as well as collegiate athletics as a whole. In the 2021 football season, attendance at Kyle Field averaged over 100,000 per game, with two fall matchups reaching the program’s all-time top-5 leaderboard.

This, in turn, boosted A&M football to a number of other instances of national recognition, including a No. 1 student section claim by ESPN analyst Kirk Herbstreit in 2006, a No. 1 gameday experience recognition from Sports Illustrated in 2011 and Taco Bell’s 2018 Live Más Student Section of the Year award.

“It’s one of the greatest traditions in all of college football,” Fisher said. “What I love about it: it’s a selfless tradition. It’s not about one person. It’s about … going in to help and wanting to be something extra.”

This support translates into digital followings as well. As of presstime, the A&M football team’s Twitter account has nearly 270,000 followers. When now-junior deep snapper Connor Choate was announced as the new 12th Man on Saturday, Aug. 28, of this year, fan response was unlike anything he had ever experienced, Choate said.

“When I was named the 12th Man, Twitter and Instagram went crazy. I immediately had a bunch of messages and follows and tweets supporting me, so it was definitely overwhelming,” Choate said. “But it definitely made me feel like I had a bunch of support at my back.”

In a world which so-heavily emphasizes this social media validation, the 12th Man’s longevity and commitment to its roots is what makes the tradition as special as it is, Fisher said.

“In today’s time, with the individuality of everything in which we do — the self-gratification and the ‘me, me, me’ world — the 12th Man is still about the team,” Fisher said. “To me, that makes it one of the great things that I want to be in front of.”

Fisher is not the only member of A&M leadership to recognize this feat. As the 100-year anniversary of the 1922 Dixie Classic quickly approaches, A&M has introduced a months-long celebration in the lead-up to Jan. 2: the 12th Man Centennial.

The centennial included special celebrations of various sporting events around Aggieland, new merchandising opportunities, music festivals and firework displays, among other events as well.

With the festivities celebrating a legacy he now represents every Saturday at Kyle Field, Choate said the 12th Man has taken a new meaning to him and others on the football team.

“It still feels surreal at times when I see [the No. 12] in my locker and on my jersey,” Choate said. “It’s a great honor, and I’m very blessed to be 12.”

Though he passed away on Dec. 7, 1976, at the age of 74, Gill’s legacy lives on. In his 1964 Muster speech, Gill left attendees with six key ideals, which many current and former students have now committed to heart: Respect, Excellence, Leadership, Loyalty, Integrity and Selfless Service. That, he said, is what the 12th Man is truly about.

“I’ve never thought that the 12th Man really belongs to a personality,” Gill said at the 1964 campus Muster. “It belongs to the A&M student body. Every one of you can be a 12th Man if you stand up for what’s right and be ready to serve.”