Performances featuring actors in blackface were prevalent throughout the U.S. for much of its history, and though it is not nearly as common today, its effects remain pervasive.

Blackface is a style of theatrical makeup in which people paint their faces in burnt cork, greasepaint or shoe polish. Often accompanied by enlarged, painted-on lips and ripped clothing, the practice was especially popular before the Civil War and the emancipation of slaves. It was used in minstrel shows, similar to comedic musicals, to mock African-Americans by stereotyping their appearance, way of speaking and type of work.

The first minstrel shows were performed in the 1830s in the Northeast and later spread to border states and other regions. One of the most popular character names was Jim Crow, which became a pejorative term for African-Americans. The popularity of minstrel shows continued to grow throughout the century until the early 1900s, attracting high profile individuals, from U.S. presidents like Abraham Lincoln to prominent authors like Mark Twain, according to Joe Feagin, distinguished professor in the department of sociology.

“It was about a lot more than stereotypes because they’re visual images and our whites are enjoying it and laughing,” Feagin said.

These skits used stereotypes to mock, racialize and attack African-Americans. Showcased in these performances were stereotypical characters such as the “mammy” — represented as loud, asexual black women happily working for a rich white family. Over the decades, these caricatures would become a part of the nation’s larger media landscape.

Minstrel shows became a way to justify segregation, said Brittany Perry, instructional assistant professor of political science.

“This was before the Civil War and the emancipation of slaves, so most of these portrayals were used to justify slavery and then later after the emancipation, after the civil war, you see them being used to justify segregation,” Perry said.

Following the Civil War, racist and condemning views toward African-Americans continued to influence American society and policy. “Black codes” were created in southern states to restrict behavior of African-Americans and were called “Jim Crow” laws.

At the turn of the 20th century, radio and television provided a new avenue for minstrel shows to be available to the public. This expansion created room for controversial cinema, a prime example being D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation.”

Perry said she shows the movie in her race and politics class because it exemplifies the stereotypes of African-Americans that were used mock, demean and incite violence. Many of the characters were white performers playing in blackface and the Klu Klux Klan was portrayed as heroic.

“One of the main threads of that film was to recruit for the KKK,” Perry said. “To think that this is just harmless or that it is just for an artform or performance is very much overlooking the danger that this has caused, historically and today — thinking about how those stereotypes have perpetuated and how they feed or excite negative reaction from the rest of the population.”

After the 1930s and into the Civil Rights movement, the popularity of blackface diminished. However, the stereotypes surrounding African-Americans have been prevalent throughout society from cinema to politics.

Recently, a photo of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam from his 1984 medical school yearbook surfaced, featuring him and another student dressed in blackface and a Ku Klux Klan robe. It is unclear which costume Northam was wearing.

Although he denied allegations at first, Northam recently confirmed that he is in the photo and issued an apology, stating that the costumes were “clearly racist and offensive.” Since this has come to light, many have urged him to resign from his position, but he refuses to do so, saying he has changed since the photo was taken.

According to Feagin, a recent poll showed that about 68 percent of African-Americans didn’t want Northam to resign. Feagin said if African-Americans in the modern U.S. are willing to give him a chance, then Northam should get one.

Perry said that since the image holds symbolism that people might find threatening, Northam’s ability to govern those people can be negatively affected. Perry said that Northam needs to ask himself how his constituents view him and whether or not they trust him.

“Proposing positive changes for society that enhance the role of underrepresented groups is a very good thing, but can we find someone else who is a better representative of the population at large?” Perry said. “I have to believe that there are other options out there and there are people that exist that not only work for a community, but stand for a community.”

Many other universities, including Texas A&M, have students from the past and present who have taken part in displays of racism. However, just as the discovery of Northam’s yearbook photo launched a nation-wide discussion, the same could apply for parts of A&M’s past.

Amy Earhart, associate professor in the department of English, said it is vital to look at old documents and reflect upon them. Since the yearbooks have been digitized, they are readily available for anyone to view and analyze.

“I do think that when we look at historical documents, we can reflect on those documents, to consider present, ideas, and that’s important to have a historical record,” Earhart said. “A&M has a policy of transparency and openness with the materials that they collect, and the library understands how important these materials are for current learning moments.”

Exploring blackface in US history

February 28, 2019

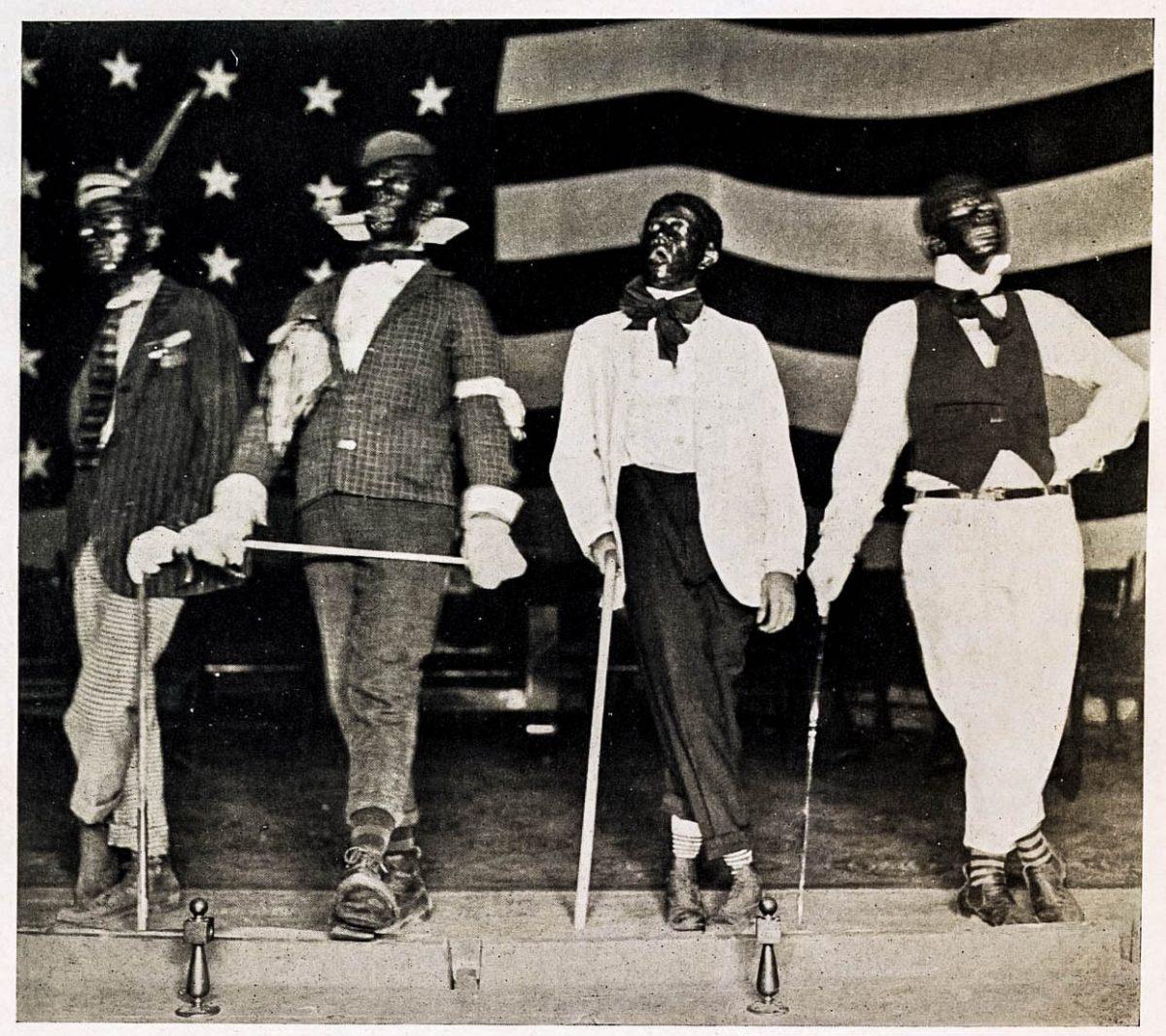

Photo by Courtesy of Cushing Memorial Library Archives

1918 Longhorn, Pg. 250: A minstrel group called the “End Men” are featured in a program for a campus music show.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover