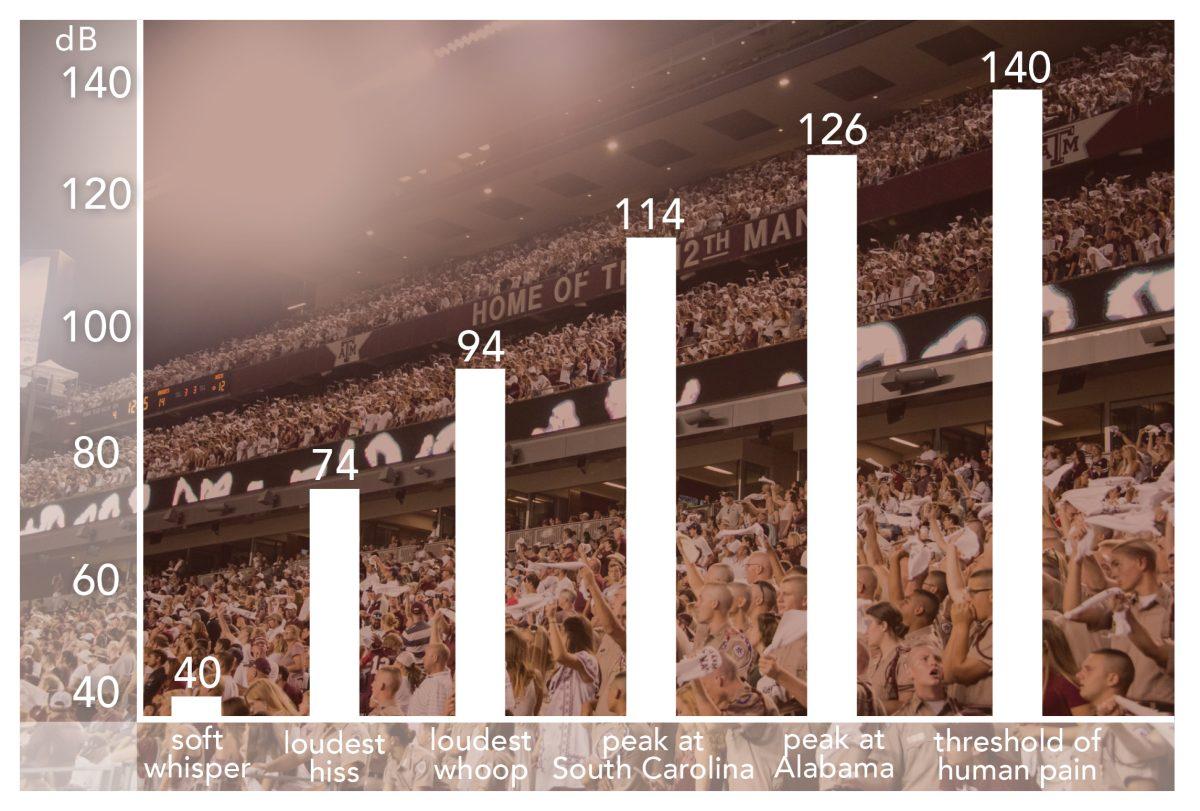

With 10 minutes and 18 seconds left to go in the fourth quarter against Alabama, over 100,000 fans erupted when Texas A&M 12th Man linebacker Cullen Gillaspia blocked a punt to force a safety, causing one of the loudest moments this season.

The saying “loudest and proudest” isn’t just talk at A&M, it is also backed up by science. For three consecutive events held in Kyle Field, the decibel readings nearly matched the sound of a jet engine and easily surpassed the noise level of a heavy metal concert.

The highest decibel reading among the A&M-South Carolina game, Alabama Midnight Yell and the A&M-Alabama game came during the Crimson Tide, when Kyle Field reached 126 decibels during the fourth quarter. To put this in perspective, the average sound of a regular conversation is 60 decibels, a night club is 110 decibels and a jet engine 200 feet away is 130 decibels, according to Occupational Safety and Health Administration — an agency that regulates safe working conditions.

There are several things that can affect how loud a stadium gets, including one’s posture when yelling. One thing Aggies do during games is the hump position — when fans bend their knees and lean forward to maximize the noise. Morgan Jenks, audiovisual researcher and assistant professor in the department of visualization, said the concrete and metal stands help reflect the sound from fans in the recently renovated Kyle Field.

“The seating capacity is a lot bigger [in new Kyle Field], so the sound sources are increasing,” Jenks said. “If there are less gaps in the concrete structure, it’s going to reflect the sound back in a lot more. It’s probably going to louder down on the ground level and in the corner since there are more waves reflecting to the field.”

Jenks said sound can be seen as big and small vibrations in the air, and heat will make sound waves travel faster since air molecules at higher temperatures have more energy and can vibrate faster. During the Alabama game, the temperature in College Station had a high of 79 and low of 66 degrees Fahrenheit, which played a factor in the maximum decibel reading in the fourth quarter.

During both the Alabama and South Carolina games, the decibel readings fluctuated from 99-109 decibels and increased two decibels on third downs for the opposing team. In the the fourth quarter, the readings increased by four decibels than in the previous three quarters.

During the A&M-South Carolina football game, the loudest moment came at 114 decibels with 13 minutes and 13 seconds left in the fourth quarter when A&M scored a touchdown, which was later overturned due to a flag on the play. The loudest yell at the Alabama Midnight Yell was 112 decibels, the loudest “Whoop” was 96 decibels and the loudest “Horse laugh” was 76 decibels.

Thomas Ferris, industrial engineering associate professor who works with sound in human engineering, said an individual’s hearing system will adapt to the surroundings, similar to how the visual system adapts to different levels of light.

“After an Aggie [football] game — assuming you’ve been sitting in a loud section — you have that period after the game, where it seems you need everything to be louder to be able to hear at a normal level,” Ferris said. “You may find yourselves shouting at your friends as you’re driving home. A lot of this has to do with the temporary threshold shift — just like how human’s visual system adjusted to different light levels — it takes a little longer, but the auditory system will adapt as well.”

Spikes in noise can cause hearing damage, but short loud noises do not cause as much damage when compared to long exposure, according to Jenks.

“Once you get above 90 decibels, it can cause hearing damage … but it also has something to do with how long you’re exposed to the sound,” Jenks said. “It is potentially damaging, but if it’s just one day a week for 10 weeks, it’s not going to be that big of a deal. If it was five days a week, that would be something serious.”

Although football games can get loud, Ferris said humans are exposed to loud noises in everyday life that can affect an individual’s hearing.

“Hearing loss is something that happens as we age … but not just aging that makes ears go bad,” Ferris said. “If you were living in a very protective auditory environment your whole life, you would still maintain a good hearing level. In [our] everyday lives, we are constantly exposed to loud noises. The longer you live, the more exposure to these noises.”

Tom Netek, engineering freshman, said he has been to multiple professional and college sporting events, and the home game against Alabama was the loudest environment he had been in.

“I have been to a lot of stadiums and I’ve never heard anything like that,” Netek said. “Especially in a game where we were losing by two touchdowns and really didn’t have much of a chance. When we scored that first touchdown, it felt like the whole SEC was cheering us on. My ears were ringing, I had a headache, my chest hurt — it was amazing.”

Loudest and proudest student section

November 3, 2017

Photo by Graphic by Alexis Will

The reading of 126 decibels during the Alabama game is only 4 decibels short of being as loud as a jet engine from 300 feet away.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover