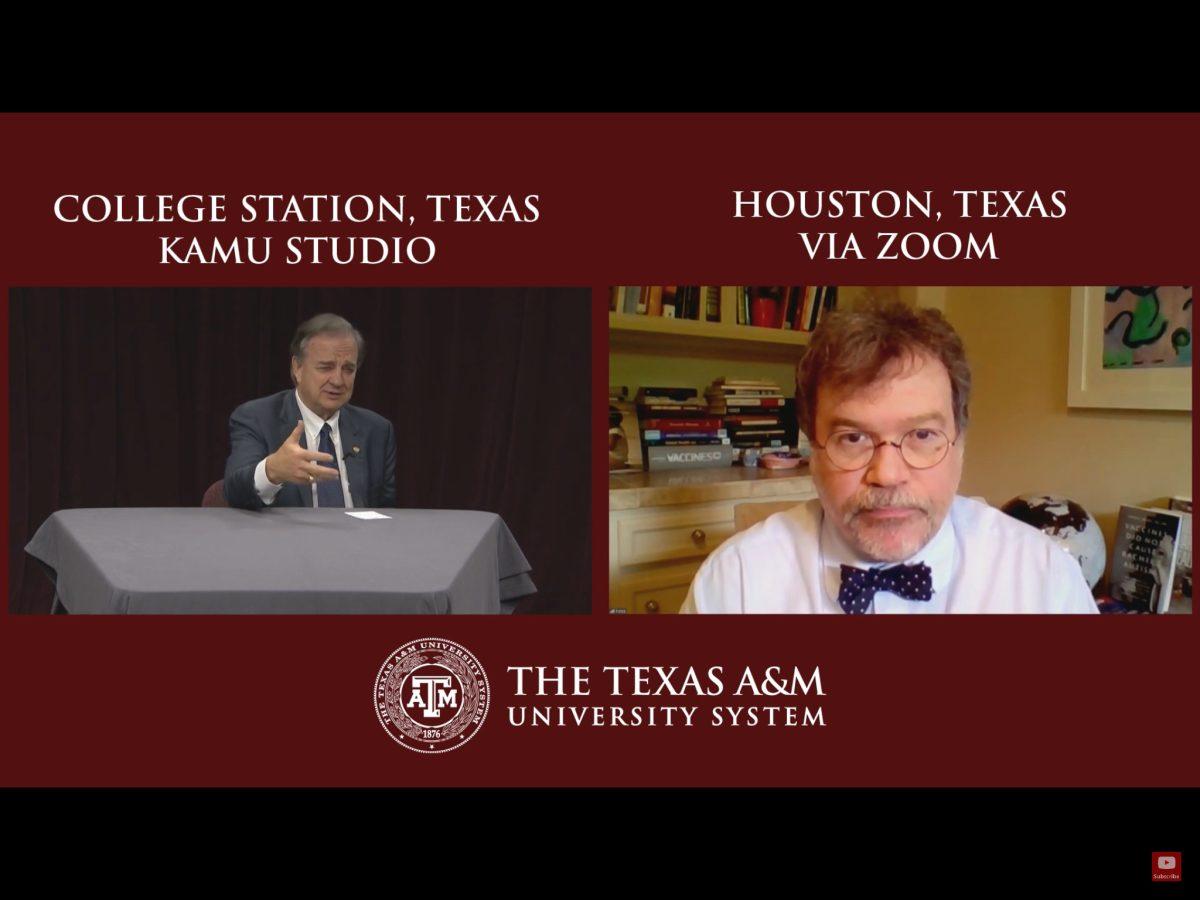

In a new question & answer series, Texas A&M Chancellor John Sharp will host various scientists, researchers and policy advisors to help the community understand the coronavirus pandemic that surrounds each one of us.

This will be held every Thursday from 7-7:30 p.m. live on KAMU and will be available on the A&M System’s YouTube channel. This week, Sharp invited Dr. Peter Hotez who is a scholar at the Hagler Institute for Advanced Studies at A&M, dean for the National School of Tropical Medicine Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and co-director of Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.

The Q&A began with discussing COVID-19 compared to other viruses, like SARS in 2003 or MERS in 2012. Hotez said although COVID-19 has a high mortality rate similar to SARS and MERS, there is a portion of the population that does not get very sick.

“It is not the most lethal or the most contagious, but it is high in both categories and that seems to be creating a very toxic mix,” Hotez said. “That means you have a large cohort in the community that’s transmitting the virus then a population getting very sick and then flooding in the hospitals and ICUs. That is why it is creating as much chaos right now and spreading across the United States.”

Hotez said the new estimates report the United States is going to be a peak in the number of cases in mid-April, however, Texas will probably peak the first week of May. A death toll of 4,000 throughout the months of May and June is predicted based on models of New York and other states. Hotez said there are beds and ventilators ready to tackle the rise of COVID-19. One concerning factor is the urban/suburban vs. rural divide, which implies cities such as Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin will get hit severely.

“The Institute of Health Metrics, which is the [model] I am looking at the closest, says it would be bad in May and June and at the beginning of June it will start to subside and we can open things up a bit,” Hotez said. “But, again, we are going to have to take this a few weeks at a time.”

Another theory floating around is that warmer weather affects the virus just like the seasonal flu. Hotez said there is some evidence but it is not strong. Without having been through a full year of this virus, there is no guarantee the climate has a strong impact.

Various treatments have been thrown around by the Food and Drug Administration that include chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, antimalarial drugs and stem cell treatments known as convalescent antibody therapy, in which plasma is harvested from patients with a high volume of COVID-19 antibodies. Currently, the FDA and academic health centers have acquired 20 such patients to begin testing. Antimalarial drugs have been shown to kill the virus in a test tube, and the clinical trials conducted in China and France have shown some promise. However, a decade ago the same thing happened with influenza but it did not pan out on a larger scale, Hotez said.

Hotez is optimistic there will be a vaccine to fight COVID-19; the challenge is that it will take time and it is difficult to rush. The Ebola vaccine took five years to create, hence there is very little chance we will have one by the end of 2020. The vaccine that Hotez is working on is focused on low-cost for it to be accessible to low- and middle-income countries.

“Vaccines have an enormous promise for preventing this infection,” Hotez said. “I don’t think we will have it by the end of 2020, so we won’t have to necessarily for this epidemic. But remember this will likely become a global problem. It will move into the southern hemisphere. … It is also likely to take on some kind of regular pattern here in the United States, some kind of seasonal pattern. We don’t know that for sure.”

According to Hotez, these vaccines should have been created before this epidemic hit, but due to the failure to cooperate with various parties, it was not possible. However, Hotez said A&M has a strong presence in trying to solve the bigger problem and facilitates these much-needed conversations.

“A lot of our failures are public policy failures,” Hotez said. “The biomedical scientists are not engaged in adequate dialogue with social sciences and people in the humanities.”

Families with small children need to take precautionary measures just as those with high risk. Kids are often not getting sick with COVID-19. However, they can still transmit the disease to those who are at risk. A new development has shown that about 10 percent of infants under the age of one are getting sick, increasing the need for social distance.

One misconception is that more people have died of influenza, so there is no need to shut down the economy for this virus. Hotez said that may be true, but COVID-19 is four to five times more lethal. Using Italy as an example, Hotez said as numbers increase in Italy, the hospitals are not able to take care of such a large number of patients, so the mortality rate spiked to 10 percent. To prevent this from happening in other countries, aggressive social distancing must take place.

“Without the benefit of a vaccine, all we have are 14th-century methods to take this on, if we don’t have the technologies and that is social distancing,” Hotez said. “We know it’s a huge hit on the economy, but if we can prevent individuals from coming onto hospitals and overwhelming the hospitals, that can make a difference in the number who die.”

Sharp launches weekly Q&A series with distinguished healthcare professionals to discuss COVID-19 implications

April 9, 2020

Chancellor John Sharp, launched a weekly COVID-19 question & answer series with Dr. Peter Hotez, a world-renowned physician specializing in vaccinations.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover