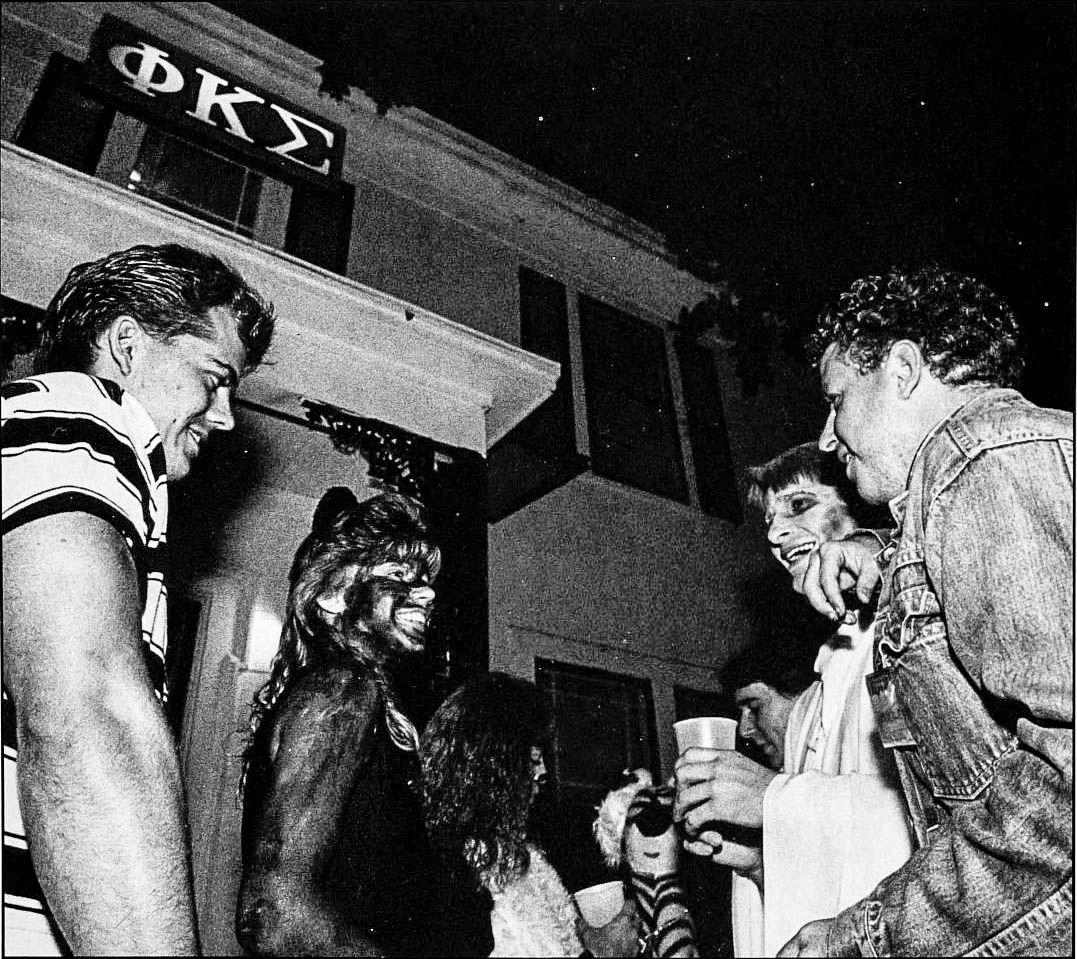

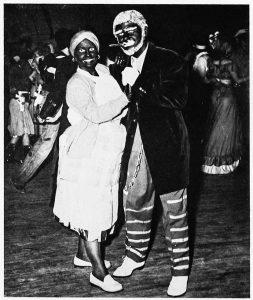

Blackface pictures and other racist images from University yearbooks have surfaced across the country, reminding the nation of its notably recent past. Texas A&M is not exempt from this history, and the university’s own yearbooks contain numerous racist images.

The Aggieland, formerly known as The Olio and then The Longhorn, was founded in 1895 during a period of racial segregation. Blackface had been popular since the 1830s, when an actor named Thomas D. Rice created a character called Jim Crow, which essentially mocked and denigrated African-Americans, according to associate professor of English and coordinator for the Africana Studies Program Michael Collins.

“It helped to create these horrible stereotypes that blacks were foolish and irresponsible and not really capable of complete citizenship,” Collins said.

Collins said that while looking through yearbooks, he discovered that E.J. Kyle — for whom A&M’s football stadium is named — suggested in 1910 that the school form a minstrel troupe.

“As a result of that, the A&M Minstrels were created, and some of the blackface images in the yearbooks are of this A&M Minstrels troupe,” Collins said.

Instructional assistant professor of political science Brittany Perry, who specializes in race and ethnicity, said thinking of blackface as harmless, or just an art form or performance overlooks the danger that it has caused.

“Up until today, we can often think that this is not deliberate and people don’t know about the history or the legacy of blackface,” Perry said. “But when you look at something like Ralph Northam’s yearbook and the man in blackface standing next to the man in KKK uniform, you know that they understand that connection, and that is a connection not to be overlooked or to be brushed away.”

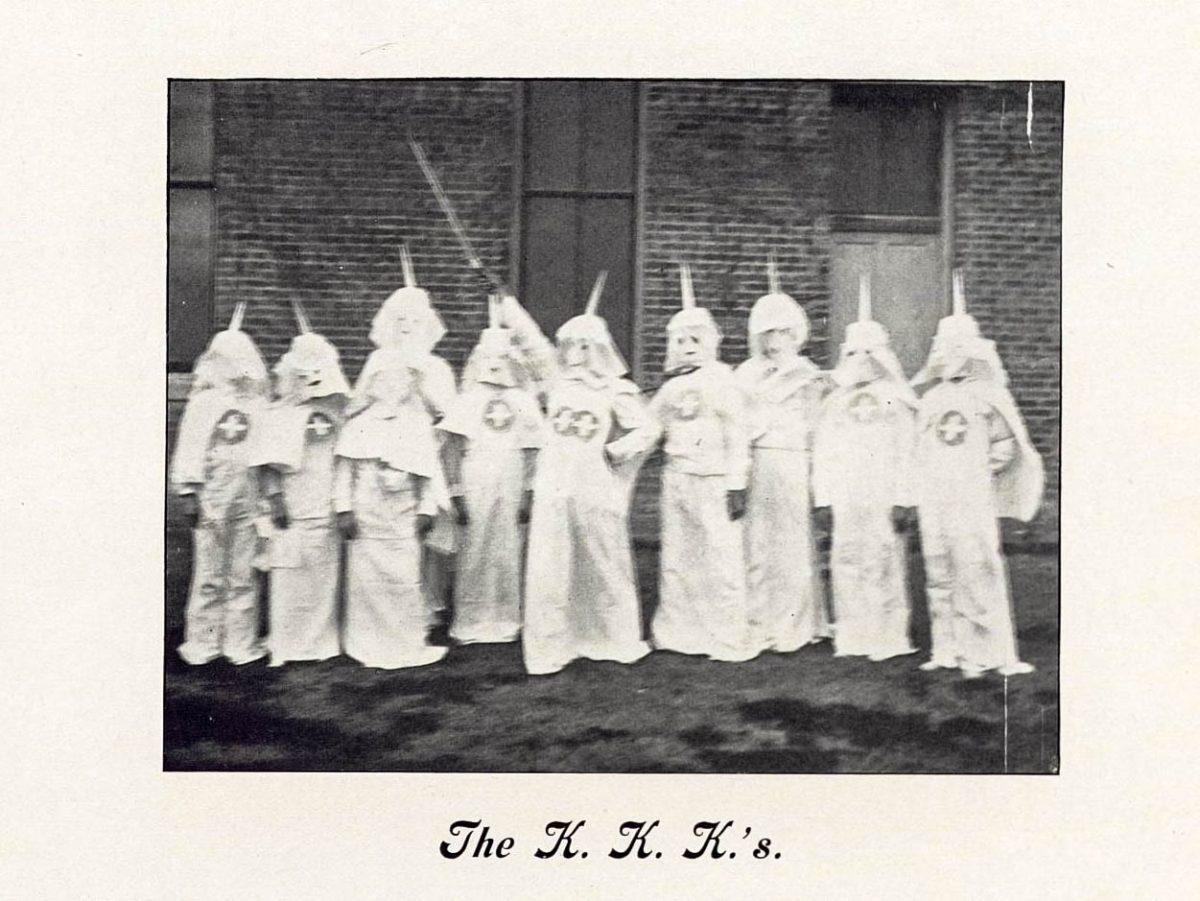

Images of A&M students in blackface are not limited to the early 1900s, and instances of the racist practice have been documented as recently as 2006, when a video was published on YouTube showing an A&M student in blackface being whipped by another student.

Other instances of students dressed in blackface include the “jungle fever” party in 1992, which was hosted by the fraternity Sigma Alpha Epsilon. The party included both blackface and “slave huts,” according to Cushing Library’s archival project “In Fulfillment of a Dream.” The Interfraternity Council, backed by A&M administration, imposed sanctions on the fraternity for the racist actions, according to a Battalion article from then.

“The key to all this is education; the sanctions are only a part of the solution,” then-Vice President of Student Affairs John Koldus said. “A lot of the responsibility rests with the leaders of the institution. We simply have to do more things to make people aware.”

A&M’s yearbook is not the only student publication that has printed racially charged images. A 2002 Battalion cartoon published by anonymous student “The Uncartoonist” faced criticism for its portrayal of African-Americans. In an article from that time, the Houston Chronicle described both the cartoon and the ensuing backlash.

“[The cartoon] depicts a black mother scolding her son for flunking a class,” the article reads. “Both the mother and the son have big eyes and frowning, large lips — caricatures historically used to denigrate blacks.

“The overweight mother — holding a spatula in her left hand and wearing an apron and curlers — points to her son with her right hand and says, ‘If you ain’t careful you gonna end up doing airport security.’”

The African-American Student Coalition demanded that The Battalion apologize, saying the cartoon was “blatantly racist.” In a letter published in The Battalion, then-University President Ray Bowen wrote that the cartoon “clearly played on stereotypes of African-Americans.”

Collins said an understanding of A&M’s past is essential for current students, especially when examining more recent displays of racial malice.

“I think it’s good to have a push for current students to understand the A&M past because otherwise, they can’t really understand why, as some people basically don’t understand what’s wrong with blackface,” Collins said.

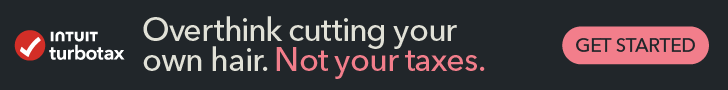

Yearbook history is not limited to images of blackface; pictures of students dressed in Ku Klux Klan robes can be found in at least two instances — one group photo from 1906 and a lone student at Midnight Yell pictured in the 1966 Aggieland.

Additionally, a club called the Kream and Kow Klub emerged in the 1921 edition of The Longhorn. The group kept this name for almost 40 years — occasionally switching the spelling of Klub to Club — before entirely changing its name to the Dairy Science Club in 1959. University archivist Greg Bailey said that there had been speculation regarding the club’s name, but the reality is ultimately unknown to him.

“I don’t have a good answer why the Kream and Kow Klub decided to use a K for all of their things,” Bailey said. “I have not been able to find good documentation on why they came forward and said, ‘We’re going to use this.’ People presented the obvious, but I don’t know.”

An entry on the club’s page from the 1956 Aggieland simply says “it is spelled with all K’s because it was founded in the days of the Ku Klux Klan.”

In 1993, the KKK planned to have a rally in College Station, according to an article in The Battalion. A high-ranking Klansman said members of the Klan who were enrolled at A&M suggested the rally be held at Oaks Park, though it’s unclear whether the gathering ever materialized.

“Grand Dragon Michael Lowe said the KKK will appear on behalf of requests from members who are A&M students,” the article read. “He said about a dozen A&M students are members of the KKK.”

University archivists strive to preserve all records of the past, both good and bad so that individuals can see the full picture of A&M’s history, Bailey said. However, sometimes parts of collections are removed before they reach archivists for preservation.

“There’s always more of a story than it might just be in the official records,” Bailey said. “In archives, we don’t try to sanitize things. But unfortunately in the past — and it probably can still happen today — before records are transferred to the archives, people sanitize records, possibly things that might not reflect kindly on the past.”

Patrick Zinn, director of marketing and communications for the library system, said helping people understand the whole story through access to multiple sources is one of the jobs of university libraries.

“You can’t look at any one piece of information and discern everything about an institution,” Zinn said. “Although there [are] some abhorrent pictures, maybe even some other information, it’s not the whole story, and it’s never the whole story.”

According to Bill Page, library associate for the Ask Us Services, the facts of the story stay the same, but the story you choose to tell can be very different.

“You can have affection for the university,” Page said. “You can be proud of the university and still be a willing advocate to change the university.”

Facing A&M’s past

February 28, 2019

Photo by Courtesy of Cushing Memorial Library Archives

1906 Longhorn, Pg. 198: This photo of students in Ku Klux Klan robes appeared in the clubs section of the yearbook, along with a list of group’s members.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover