Texas lawmakers are attempting once again to place a statewide ban on texting while driving, hoping that a change in the governor’s office will yield a different result.

Rep. Tom Craddick authored the bill, which has now passed through committee and is expected to be read on the House floor Wednesday. Craddick previously brought forth legislation about texting while driving only to have the legislation vetoed by then-Gov. Rick Perry.

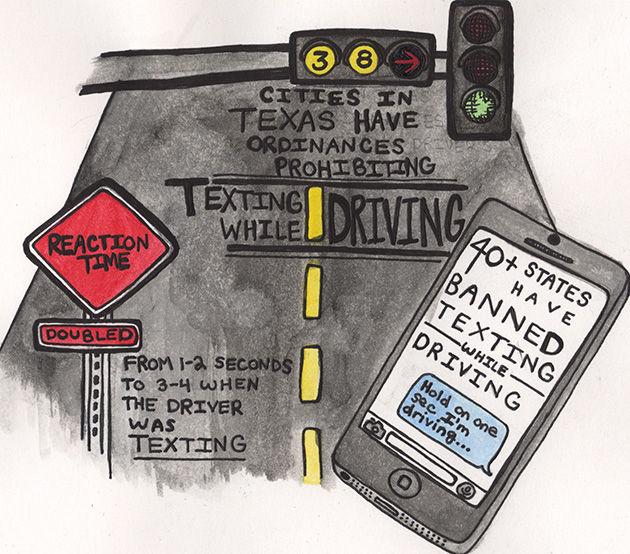

“When I first filed, only nine states had done it or were looking at it,” Craddick said. “Now 44 states have passed it and 38 Texas cities.

In Texas, texting while driving falls under distracted driving, one of the top five causes of vehicular accidents. In 2013, the Texas Department of Transportation reported 94,943 crashes due to distracted driving.

If passed, HB 80 would expand on current legislation that outlaws texting in school zones and prohibits all texting, even if the vehicle is stopped at a light or stop sign.

“An operator commits an offense if the operator uses a portable wireless communication device to read, write, or send a text-based communication while operating a motor vehicle unless the vehicle is stopped and is outside a lane of travel,” the bill states.

Consequences for texting while driving would be fines of more than $99 for a first-time offense or $200 if the offender has been previously convicted for the same offense.

Alva Ferdinand, assistant professor at the Texas A&M Health Science Center School of Public Health, has conducted studies on distracted driving and testified about her research to the Texas Congress.

“Studies have shown that individuals perceive the risk of having an accident due to cell phone distraction is less for themselves than it is for their peers on the road,” Ferdinand said. “In other words, we have more confidence in our own abilities to safely operate a car while texting than we do for others’ abilities.”

A number of the studies referenced come from Texas A&M, including the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, where Christine Yager, associate transportation researcher, worked on one of the first published studies in the United States to examine texting while driving.

The study, which included driving simulations, showed that texting while driving doubles the reaction time behind the wheel from one to two seconds to three to four. In five seconds, a car traveling at 30 mph will travel approximately 220 feet.

“Texting in the traditional sense requires the use of your hands and eyes — compared to say, talking on a cell phone may only require your hands,” Yager said. “The more that you divert attention and resources — eyes, mind or hands — away from driving, the greater your risk of a crash.”

Still, the critique remains that a ban on texting while driving in Texas is a violation of a driver’s freedom, cited by Perry when he vetoed Craddick’s original legislation.

With Gov. Greg Abbott in office, Craddick said there may be a higher chance of passing the bill this session.

“The governor’s people have been at the hearings we’ve had, they came to the press conference we originally had and I think they’ve offered an amendment that we’re going to take, and hopefully if we pass it in the House and Senate he’ll sign it,” Craddick said.

Abbott stated in 2014 that he would likely veto a bill to ban texting while driving. However, in an interview with WFAA Sunday, he said it was something he would have to look at closer, although he said he still had concerns of the state establishing too many laws to restrict Texans.

“I want to see the dangers posed by texting while driving addressed,” Abbott said in the interview. “One death, one injury, because of texting while driving is one too many. At the same time I don’t want to turn Texas into a nanny state. This is a law I will have to take a very close look at if it passes.”

Other critics of the bill claim that policing the prohibition will not be effective. To this, Craddick said people have been shown to change social mindsets when laws are established.

“Statistics show that 95 percent of the people, if you make a law, they respond it and obey it,” Craddick said.

Ferdinand said her team saw this change of mindset in their research.

“We were not expecting to see that states with texting laws have seen significant reductions in crash-related fatalities relative to states [like Texas] that don’t have such laws,” Ferdinand said. “This was because laws requiring changes in behavior, such as seat belt laws, have historically taken several years to become truly effective. Our findings indicate that the presence of these laws and attempts made by law enforcement are serving to compel drivers to refrain from texting while driving when they otherwise would not.”

Ferdinand said if the bill is passed and signed, the next step would be to involve several players to ensure these critics’ prediction doesn’t become the case.

“Given that several states have seem improvements following the implementation of texting-while-driving bans, it wouldn’t be surprising if the state of Texas made efforts to reach out to agencies and law enforcement in other states to learn about the pitfalls and best practices for effective implementation,” Ferdinand said.

After a time of adjustment, Yager said the law would likely become part of the everyday function of the state if passed.