It is one of North America’s longest natural migrations, and it could be in danger of vanishing.

Millions of monarch butterflies trek across the United States on a migration from Central Mexico to Canada every year, but a mixture of changing agricultural practices and climate change have reduced the number of butterflies to a fraction of what it used to be. The losses in recent years have been especially severe, and researchers at Texas A&M and elsewhere say the migration is in danger of disappearing altogether.

“The monarch [butterfly] is found worldwide,” said Craig Wilson, a senior research associate at Texas A&M’s Center for Mathematics and Science Education and longtime butterfly enthusiast. “It’s not going to die out in North America, but the migration is what’s under threat, and that’s the miraculous thing about them.”

Monarch butterflies migrate en masse from Canada to Mexico and back every year because they cannot survive the colder northern winters. This spring marks the start of the monarch’s return north, a journey that begins in the mountains of Central Mexico before sweeping through Texas and the Midwest on its way to Canada.

Wilson said the migrating butterflies will face severe challenges on their journey north because of the scarcity of an all-important plant necessary to their survival – milkweed.

“Because of the extended cold spells and the longer winter, there is very little milkweed available at the moment, so when they do get here, unless things get a move on, they will be limited as to where they lay their eggs,” Wilson said.

Monarch butterflies only lay their eggs on milkweed, a type of wildflower common to the Great Plains that can often be spotted on the side of interstates. Besides the recent cold, Wilson said the introduction of herbicide resistant cash crops, and the farming industry’s emphasis on growing corn to meet ethanol’s rising demand, are factors that have made milkweed scarce.

“You have millions of acres that would have supported wildflowers and milkweeds but now when the farmer goes to spray pesticides, the corn and soybeans survive but no other weeds, so that habitat is lost,” Wilson said. “The price of corn is so valuable now that people aren’t going to stop using it, so we’re just going to have to find ways of mitigating it.”

Wilson is one of several voices in the scientific community trying to bring attention to the monarch butterfly’s plight. Orley Taylor, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas, founded monarchwatch.org, an organization concerned with monarch conservation. He said the role Texas plays in reducing or expanding its milkweed growth is pivotal to the

overall migration.

“Texas is clearly the most important state for monarchs for two reasons,” Taylor said. “The butterflies now coming out of Mexico need the milkweed in Texas to get that first generation going. If there are no milkweeds in Texas, believe me, there aren’t going to be very many monarchs in the United States.”

Taylor said milkweed is poisonous to many of the monarch’s predators, and the butterfly’s evolution took advantage of this toxicity as another way to protect its vulnerable larva. This advantage however ties the monarch’s ability to reproduce to the amount of milkweed available, a relationship that endangers the butterfly when milkweed becomes scarce.

Neither Wilson or Taylor expect a reversal of current farming techniques to promote milkweed growth, but Wilson said there is a different common practice that can be modified in order to make Texas and other U.S. states more monarch friendly – mowing grass.

Wilson said many cities mow the vegetation that grows alongside highways before the wildflowers that grow there, including milkweed, have a chance to seed.

“If they would hold off until all the wildflowers have seeded, including the milkweed, then those would come back again next spring,” Wilson said. “There’s a tendency to just cut it when they stop flowering, and they don’t leave enough time for the flowers to go to seed. If we could arrange for cities to do that, we’d be good.”

A more direct approach would be to plant milkweed alongside much of the interstate highway system. Wilson said such an initiative would mirror Lady Bird Johnson’s highway beautification program, and would give the monarch migration a better chance at survival.

“If [the interstates] could be planted with milkweeds, it would perhaps provide some corridors where the monarchs could survive,” Wilson said. “But it would take a huge cooperation between the states.”

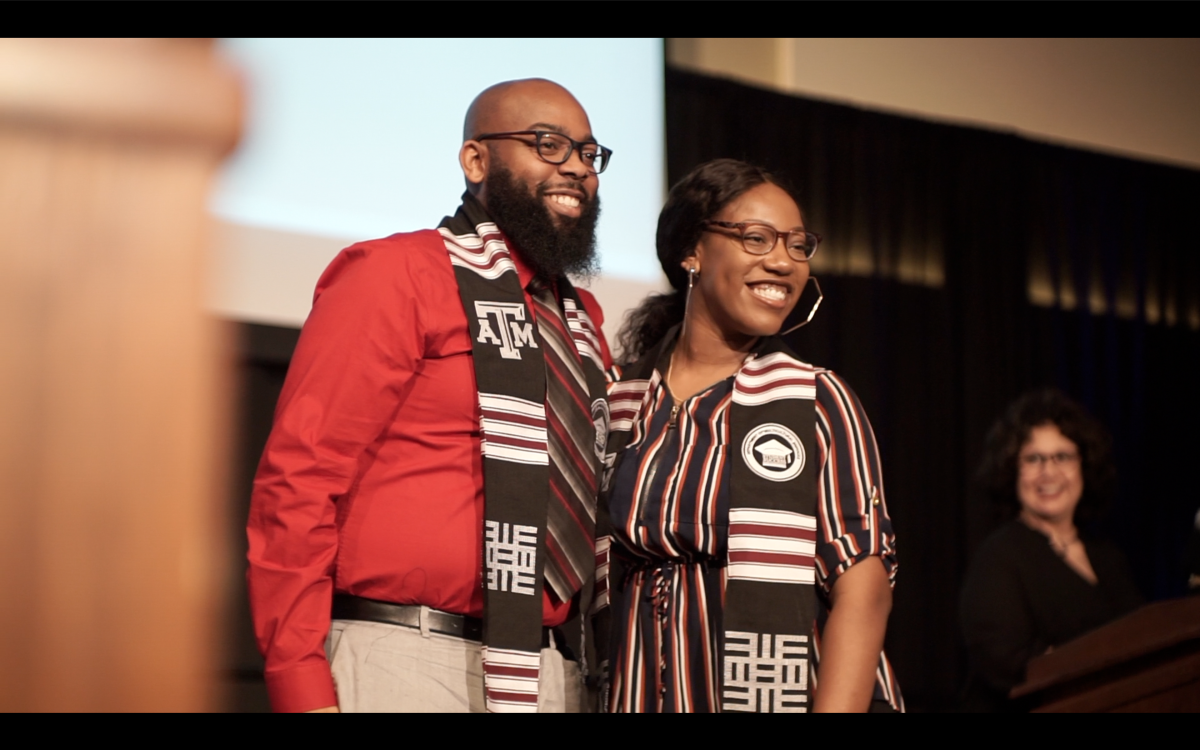

Wilson is also responsible for the creation of several monarch “waystations” throughout Bryan-College Station. Waystations are gardens certified by monarchwatch.org that contain milkweed, nectar plants and other traits favorable to monarch migration.

Four Bryan-College Station elementary schools are home to waystations, and the Cynthia Woods Mitchell Garden is a waystation with more than 400 milkweed plants.

Karen Kaspar, principal of Mitchell Elementary in Bryan, said the monarch waystation has drawn butterflies and local wildlife to the school garden ever since its creation three springs ago.

“We do notice some [butterflies], and we do get a lot of really neat birds and rabbits that come in [to the garden],” Kaspar said.

Plight of the Monarch

March 24, 2014

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover