Picture this: The raw beauty, blondness and porcelain skin of Aphrodite in “The Birth of Venus.”

She stands in the center of a grandiose, pearlescent clam shell. She is naked yet modest. She is vulnerable. Her natural beauty, which transcends and splices through time and space, takes full, frontal force. Aphrodite, the goddess who comes down from Venus, is the epitome of desire. She is elegant, otherworldly, unattainable — and that’s the entire point. You can never become her. You can only consume her with your eyes. She is truly a work of art.

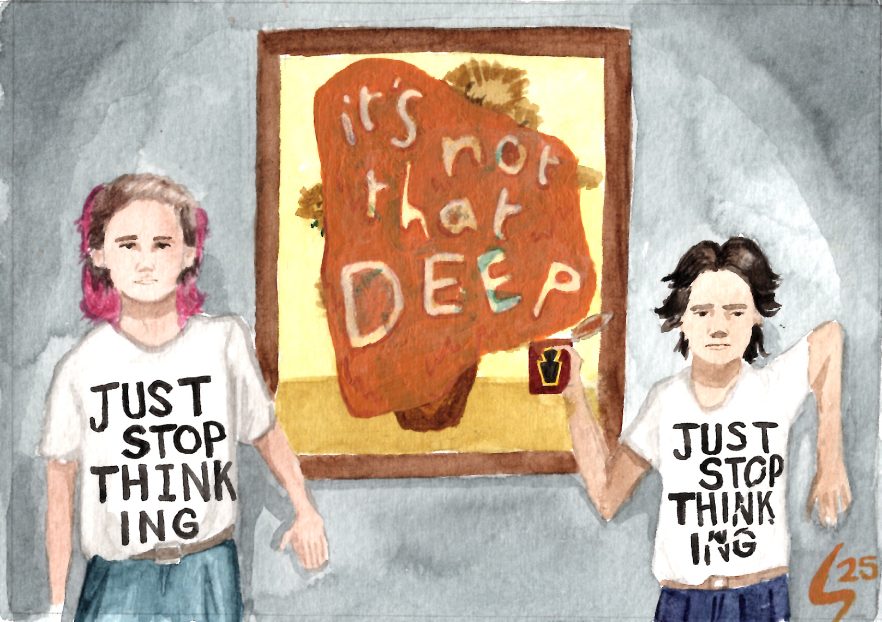

Every day we come into contact with representations of ideals; models who grace the covers of magazines and makeup counters at Dillards, movie directors who hire said models to cover up how bad their plot is and our own friends who are born with a naturally chiseled mog become the center of comparison. We can’t all be the Gigachad that intimidates and graces every beta’s presence at the Rec Center.

Beauty is only becoming more democratized through our access to Pinterest, TikTok and photo editing apps. Man, woman, anything outside or in between, it helps tremendously to be desirable. However, beauty remains unattainable, even as we reach for the next product, the next trend or the next compliment. It somehow slips away and sneaks into the night, the instant we fall behind or can’t keep up with how fast our society’s concept of beauty changes — and it’s only becoming more exhausting.

Every day I’m in this unsustainable race against myself that I cannot even place in.

I need to be a better version of myself, and how I look is at the forefront of my insecurities. I need to be perceived in a very meticulous way that can only be described as self-induced insanity.

Every detail and every fiber of my being needs to be spun, turned into yarn and weaved into a perfect pattern. My Pinterest board is filled with women I will never look like even if I spend copious amounts of time perfecting my foundation base or biting the bullet on a rhinoplasty. I hate having eyes so critical of myself, and I cannot stress it enough — it feels like there is no escape.

My Instagram feed is flooded with celebrities who are edited to look more aesthetically pleasing than the next, as their rib cages dramatically curve in and their faces are completely smoothed. I’m stuck in an algorithmic feedback loop in which my insecurities start developing themselves. At age seven, I’m complaining about my nonexistent thigh gap. At age 12, I’m worried that my pores are too big. At age 19, I’m wondering if anything about me is genuinely wanted if I’m not deer or fox pretty.

And in a world that treats people like consumers, we become the centerpiece of our own harsh beliefs about our beauty until it’s the only thing that can matter.

If someone hates their chubby cheeks, they can get buccal fat removal surgery. If someone thinks their nose is too big, they can shave it down, given that they have the funds for their hyper-specific project. The more insecure people are, the more they’re willing to consume products to move towards the ideal notion of beauty — Aphroditeness and its illusion.

Our internal world doesn’t have to change, while our external facade does. We don’t like to admit it, and rather convince ourselves that we are good people, but shallowness still prevails.

How could it possibly not?

Our world is filled with subliminal messages that are universally unavoidable if you live in the 21st century.

Being rightfully or wrongfully accused of being a big-back is another euphemism for being overweight. Having a rat-looking boyfriend is an insult followed up with “as long as you’re happy!” from concerned friends. Even in special, intimate moments like family pictures, we become repulsed by an unflattering angle. In that single snapshot, our critical displeasure with ourselves becomes infinite and solidified in time. We feel screwed.

Who we are becomes how we look until there is nothing left to discover about the person. I, then, have been turned into an object of my own vicarious desire, living through the idealized version of myself.

But even at the bottom of this pit, trapped in this endless treadmill of unreachable perfection, I still look above and encourage everyone to see past the immediate want to be beautiful. Self-reflecting on this desire to be aesthetically pleasing has led to slight changes in my habits.

On some days now, I empty my mind completely and try to forget the standards and judgments of others. I take out steps from my makeup routine, put on clothing that’s comfortable and stop paying attention to what others say about my attraction to supposedly “odd-looking” men. I’ve learned how to appreciate my own taste and, more importantly, prioritize my own blistering, bubbly feelings for someone.

Even in these tiny, micro instances, at large, I can rest assured that at least something is changing. I can appreciate just how much I can accept that it is normal to fluctuate in weight and that my skin breaks out from time to time. I can accept that I’m not always going to look my best every day and choose just to relax. Most importantly, I can better appreciate my mother’s unique features and beauty as I come to appreciate my own.

Everyone is already put on earth as a work of perfection, whether we are created in God’s image or a completely randomized outcome of the gene lottery. I realize over and over again that a kind of beauty rests in that ambiguity alone, not in ideals or in imagery by artists from a distant past or in hyper-specific concepts.

When it comes to our own reflection, our focus shouldn’t be directed at the immediate mirror but at our minds. We should all be a little more forgiving to ourselves and decenter what is commonly seen as beautiful.

By admitting that my insecurities are deeply ingrained, I’m hoping that others who can relate know they aren’t completely isolated. At least in this vulnerable moment, there can be some semblance of beauty without having to have porcelain skin or blond hair.

Sidney Uy is a philosophy sophomore and opinion writer for The Battalion.