The Biden-Harris administration recently released a proposal to reformat the racial and ethnic categories presented in the 2030 United States Census. In efforts to improve the accuracy of data collection, new possibilities for self-identification will be presented to responders.

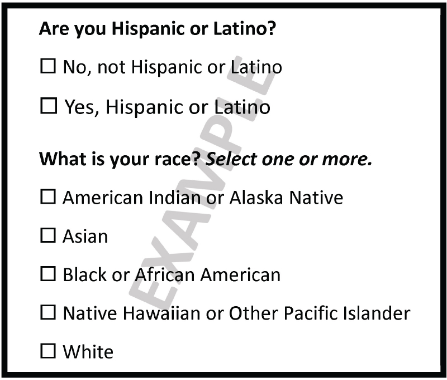

A couple major changes include giving “Hispanic or Latino” and “Middle Eastern or North African” separate ethnic categories instead of being packed into the previously all-encompassing “White” checkbox, as well as creating new options for “countries of origin.”

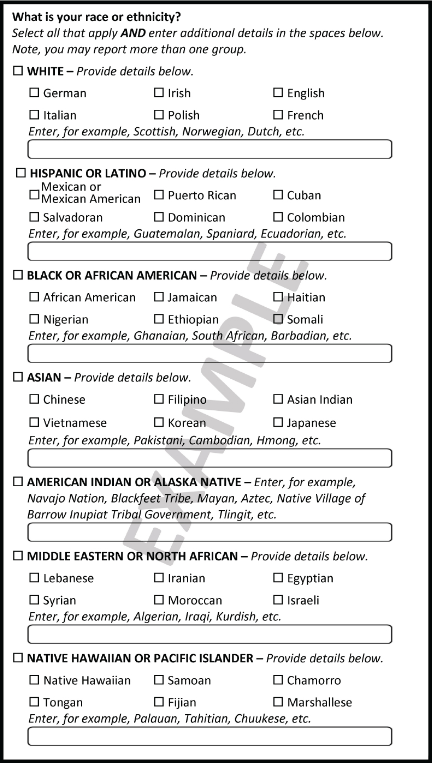

Here’s a suggested model:

A quick glance produces the same feeling you get when ordering food from a restaurant menu with six pages and 30 different entrees: Too many options to the point of being overwhelming. Polish? Somali? Mayan? Chamorro? The ability to enter additional details and report more than one group?

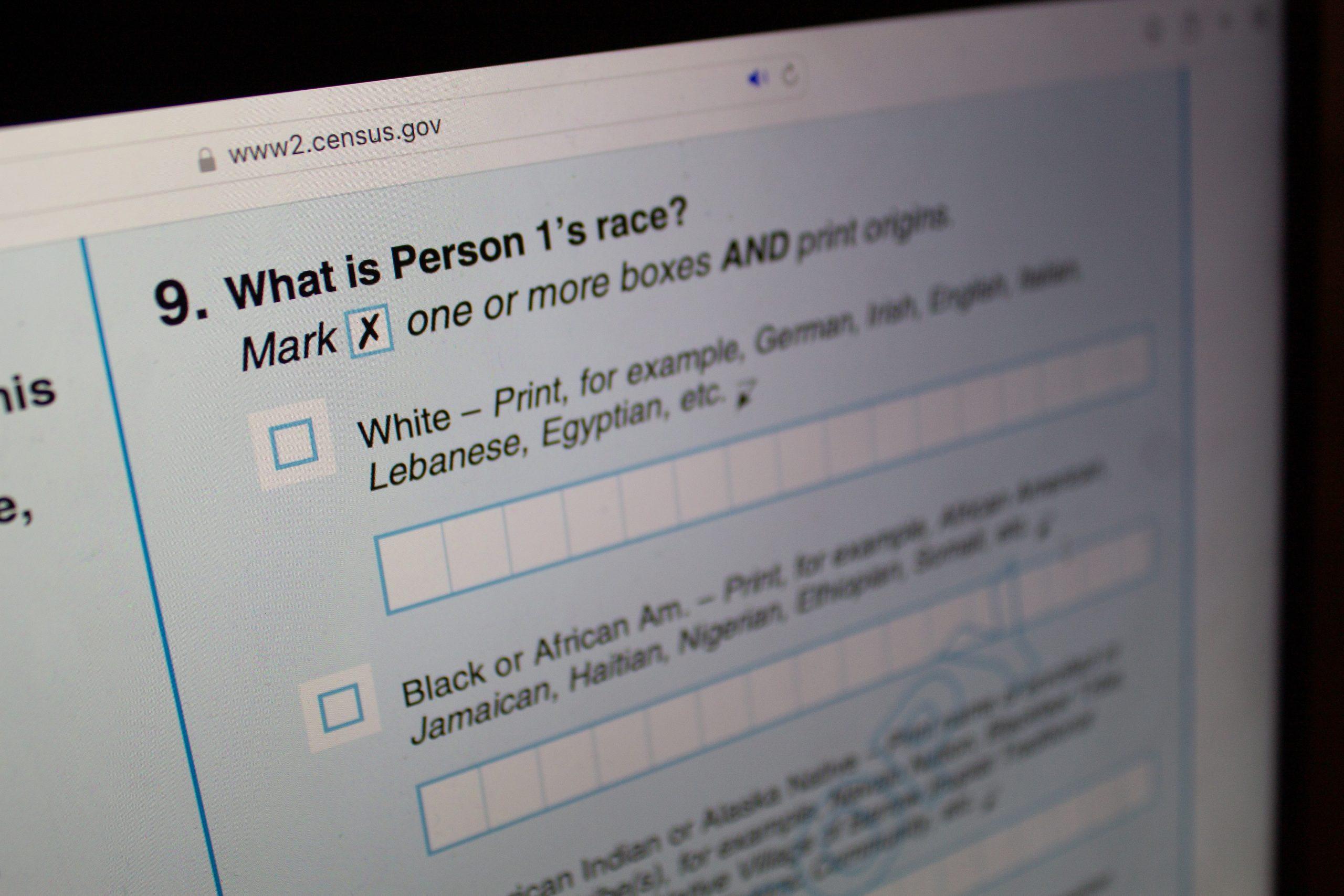

This proposal starkly contrasts the current format that presents just five options for race and a “Yes or No” question about Hispanic heritage, opening a whole new realm of choice. However, is it too much? Will these revisions truly improve inclusivity and precision, as intended, or simply fuel the confusion surrounding definitions and origin?

For many Americans, personal ancestry is shrouded by a cloud of uncertainty. It may be tempting to assume most people can confidently name their race, but in reality, even this can be unclear for many — especially ethnic minorities.

In 2015, 69% of young Latino-American adults ages 18-29 said their Latino background was part of their racial background, with 37% selecting “some other race” instead of choosing one of the five government-defined categories. However, federal policy defines “Hispanic” as an ethnicity that can be of any race. Similarly, a majority of Americans of Arab or Middle Eastern and Northern African descent do not view themselves as belonging to White or White American groups, according to a 2021 research study.

As an Ecuadorian-American, I can see where this misconception and sense of alienation stem from — putting a checkmark next to “White” can just feel wrong. Why wouldn’t it, when our appearance, culture and language starkly set us apart? To be categorized the same as Donald Trump and Dolly Parton for the sake of population data is comical, to say the least.

Though part of me wants to say it’s not that big a deal, I can’t help but reflect on moments in my life which prove the opposite to be true. Like how I always have to restrain myself from correcting that one person who unnecessarily points out they’re the only white friend in a group of Hispanic or Middle Eastern ethnicities. Or when I was told I’m “brown and that’s all that matters” by a Caucasian friend after trying to clarify that I’m Ecuadorian, not Mexican.

How can something “right” be so fundamentally misconstrued?

Furthermore, considering our government uses the U.S. Census to determine everything from where to build schools, homes and hospitals to the distribution of funds and assistance, it is vital to produce results that correctly reflect our country. This objective is hardly met by clustering diverse people together.

Thus, it would seem I’ve answered my own questions: A more detailed census would be more comprehensive. Yet I can’t help but wonder if tipping the scale to the opposite extreme threatens to open up a whole new Pandora’s box.

If I were to fill out the proposed 2030 model with the utmost precision, my pencil’s lead would probably wear out. Thanks to family talks and 23andme DNA tests, I know I’m about ½ Ecuadorian, 1/4 Italian, 1/8 French, 1/16 Irish, 1/32 Portuguese … the fractions trail on and on. Technically, I should also mark “American Indian or Alaskan Indian” as my race alongside white. Like millions of Latino Americans, I have significant Incan roots — an echo of a civilization long since assimilated by European imperialism.

Like myself, there are many who have a solid picture of their genetic mosaic. However, there are also those who know close to nothing about their backgrounds.

So, where should one start? Where should one stop?

There may not be a black-and-white answer, especially as America’s population has become increasingly diverse over the years. Individuals could select several nationalities and ethnicities to prioritize precision, or only a couple in honor of personal identity.

For example, though a quarter of my heritage is Italian, I do not particularly connect with this nation’s culture besides enjoying my grandmother’s eggplant parmesan and gesturing a lot with my hands when I speak. Though I don’t know much about Ireland, my last name and family history indicate a long line of Irish ancestry. Does this merit a check on a census?

My questions don’t end there — who these choices affect and how the government would translate them into policy is a whole another discussion.

Thus, we’re left with a deceivingly complex dilemma: Too broad vs. overly detailed.

All things considered, I’d say the latter is best.

The specificity of the 2030 model is a bit overwhelming and debatably inessential, but it is ultimately progress toward addressing and including people of all backgrounds, which is a much more pressing issue. Personally, I’d rather have to explore my heritage a bit than be unfairly represented by data that is vital for my political representation and education.

Unfortunately, there will probably never be a perfect solution to categorizing people based on definitions that draw heavily from social construct and personal identity, especially in a polarized and ever-evolving country such as ours.

One thing I can say with certainty, however, is that checking all the right boxes is trickier than it seems.

Ana Sofia Sloane is a political science sophomore and opinion columnist for The Battalion.

Opinion: Checking all the right boxes

February 9, 2023

0

Donate to The Battalion

$1965

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover