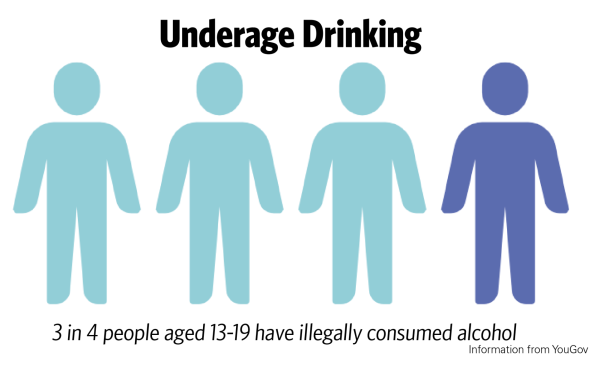

Everybody drinks alcohol, even those who aren’t legally supposed to. And let’s face it, we all know that (almost) every other Aggie has drank at least once.

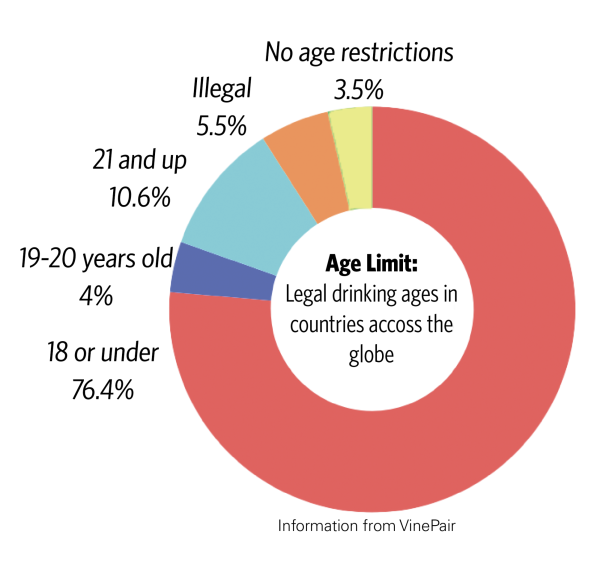

Obviously, drinking comes in different forms and intensities. Maybe your parents gave you a sip of alcohol when you were 14. Maybe you had the privilege of visiting another country — most of which have a lower drinking age than anywhere in the U.S. — and you got a drink there. Or maybe you’ve been invited to one of those stereotypical raging frat parties and gotten blackout drunk.

In any case, there’s a big discrepancy between the cultural acceptability of drinking and its legality. You’ll often hear something like, “If I can vote and be drafted for war, why can’t I drink?” That’s a good enough argument, right? Even if it’s not, it’s not like most people who were already drinking are going to stop drinking anyway.

Nevertheless, if you’re skeptical of lowering the drinking age, you probably think these arguments — among others — are simply lazy excuses for people to indulge in what could turn out to be a terrible habit.

I’d like to offer an alternative view: These one-liner critiques on current alcoholic restrictions point toward a far more devastating philosophical critique of the drinking age.

How could something as simple as the drinking age be subject to a “devastating philosophical critique,” you might ask? It all has to do with bodily autonomy — the idea of personal freedom that is commonly discussed in today’s political climate.

You’ve probably noticed that both Republicans and Democrats — conservatives and liberals — argue for the importance of freedom in certain social issues. Nonetheless, these issues vary quite widely from one to the other: conservatives might argue that the right to own firearms is a critical part of someone’s “God-given right,” protected under the Second Amendment. Conversely, liberals commonly assert that women must have the right to make decisions about their reproductive healthcare because of their “bodily autonomy.”

On the other hand, conservatives and liberals both generally object to the freedoms that the other group permits by arguing that those other freedoms might cause people to inflict undue harm or suffering on others. Basically, the freedom to own guns leads to children dying in schools, and the freedom to make one’s own decisions about reproductive healthcare leads to babies getting killed.

This is the question of every issue of personal freedom: Does the permission of a certain kind of personal freedom make harm caused by others more likely to occur? Beyond this, do governments have a moral right to restrict personal freedom that might be used to harm other people, or should the act of harm itself instead be restricted?

Quite opposite to the traditional liberal or conservative view, I would argue that the restriction of personal freedom to prevent possible harm is a disturbing and unjust perversion of what legal authority should really be used for.

Should we destroy the right to free speech because someone might incite violence? Should we legally limit who people are allowed to marry because they might end up being in a relationship where someone physically hurts them? Should we get rid of the right to peacefully assemble because people might stop being so peaceful after protesting for too long?

I think most people would intuitively answer no to these questions. If a restriction on personal freedom to prevent possible harm is absurd, so too is a restriction on adult alcohol consumption. Instead, we should outlaw — or keep the laws outlawing — specific instances where harm is occurring or where harm will definitely occur without outside intervention. Keep DUI laws, deal with abusive alcoholics and, additionally, make sure people are aware of the risks of drinking.

In short, the issue is primarily cultural. We need to stop blaming things on substances and start blaming them on people and the drinking cultures they create.

Yes, we should probably all be drinking more responsibly, but is that an excuse for the government to raise the drinking age to 25, 30 or 40? Is the possibility of suffering enough to stop anyone from allowing anything dangerous ever again? No, it certainly is not.

If World War III starts, and I get drafted but can’t drink, I’m going to be pretty mad. I bet you will be too.

Kaleb Blizzard is a philosophy sophomore and opinion writer for The Battalion.