One of the most decorated college track and field coaches, Texas A&M’s Pat Henry has made a career out of developing programs into national-caliber teams.

As a head coach, Henry has led his teams to a total of 36 NCAA Division I Championships, as well as two national titles at the junior college level and five state championships from his time coaching high school track and field.

But Henry’s success is several generations in the making.

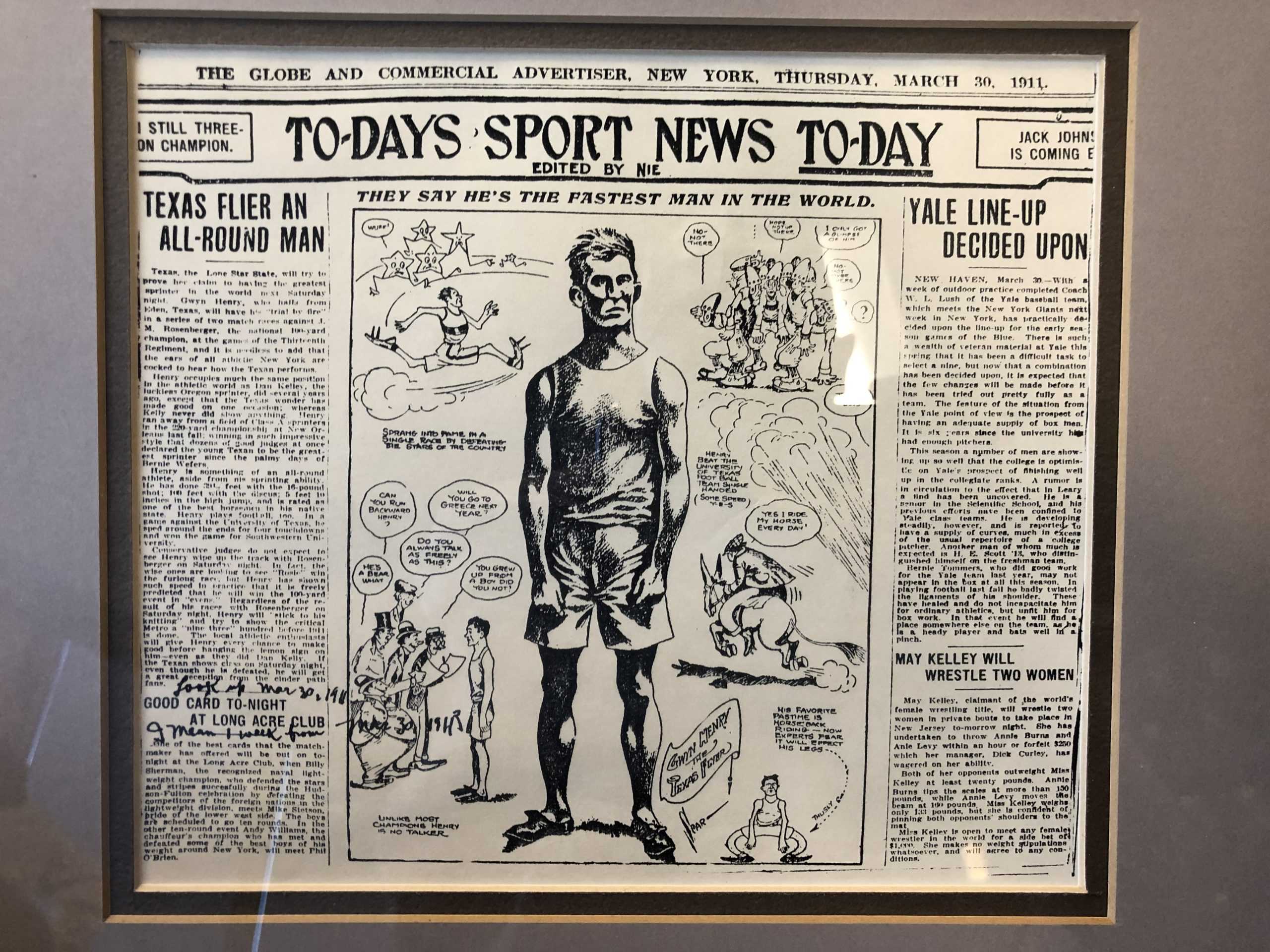

‘The fastest man in the world’

The Henry family’s entry into the coaching world began over a century ago.

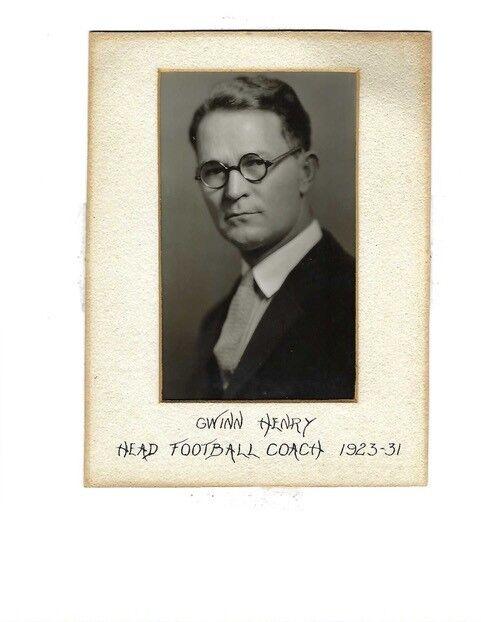

Henry’s grandfather, Gwinn Henry, was dubbed the “fastest man in the world” by the New York Times in 1911 after clocking a time of 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard dash, according to the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame, to which Gwinn was posthumously inducted in 2009.

Believed by the Henry family to be the first All-American from Texas in any sport, Gwinn was the U.S. champion in the 100- and 220-yard dashes in 1909 and 1910 and was selected to the 1912 U.S. Olympic team.

Gwinn’s athletic career began when he was a child on his family’s ranch. He and his brothers would hook a log up to one of their mules to smooth out a surface to run on, and his excellence in the sport grew from there.

“They came to learn that my grandpa was pretty good,” Matt Henry, one of Pat’s younger brothers, said. “They started going to towns around the community there … There was no TV at the time or any kind of entertainment, so men would race each other in communities and they would bet on each other.”

Gwinn, who passed away when Pat was almost four, followed up his successful athletic career with an equally impressive coaching career at the University of Missouri, the University of New Mexico and the University of Kansas.

Pat’s father, Gwinn “Bub” Henry, followed in the elder Henry’s footsteps and served as an assistant track coach at the University of New Mexico. After his retirement from coaching, Bub served as New Mexico’s alumni director and eventually the special assistant to the university’s president.

Though they didn’t know it at the time, Pat and his brothers would take the first steps toward their coaching careers as children, similar to their grandfather’s entry into the sport. While children across the country were partaking in community-wide baseball games, the five Henry brothers were bringing track and field home from their dad’s meets to the local kids.

“Even as young boys, going to track meets ourselves but then coming home and introducing it to the neighborhood so that the neighborhood was involved with track too, we were a little different in that way that we didn’t play a lot of baseball,” Matt said. “We played some, but we were doing track meets. We would do everything — we made long jump pits, we would have high jump, we even did pole vault.”

Growing up attending their dad’s track meets, New Mexico’s campus became a second home to Pat and his brothers. Matt said the boys were even involved in the behind-the-scenes duties of the meets, such as holding the finish line tape for races.

Despite the many years of coaching experience before him, Pat said he never felt pressured to follow in the footsteps of his dad and grandfather.

“It’s just the way you grew up,” Pat said. “If you grow up on a ranch and that’s what you know, you have a tendency probably to be a rancher. I think the same is true with coaching — in our family it certainly was.”

Regardless, Pat said he knew from an early age that coaching was the path he would take, though he did briefly consider going into architecture.

“I don’t remember a time where I didn’t think this is what I was going to do,” Pat said. “I thought about a couple other things, but I also knew that coaching was just what I wanted to do. I wanted to be around young people, I wanted to help people and be a teacher.”

Pat’s four younger brothers, since retired, also shared that desire, and all spent time coaching either high school or college. After having success at the high school level, twins Matt and Mark followed in their dad and grandfather’s footsteps, coaching at New Mexico as the Lobos’ head coach and assistant coach from 2000-2007, while Tim and Roben coached at high schools in Albuquerque. Matt’s son Kurt currently coaches long sprints, long hurdles and long sprint relays at New Mexico.

It was watching his dad interact with his athletes, such as three-time All-American Adolph Plummer, that “iced” Pat’s career choice, though he now recognizes that the circumstances of his life could have been much different.

“I’ve always said I’m just glad my dad and grandfather weren’t bricklayers. I’d probably be bricklaying myself,” Pat said. “There’s nothing wrong with laying brick, but I’m glad I’m coaching and not laying brick.”

Building a foundation for success

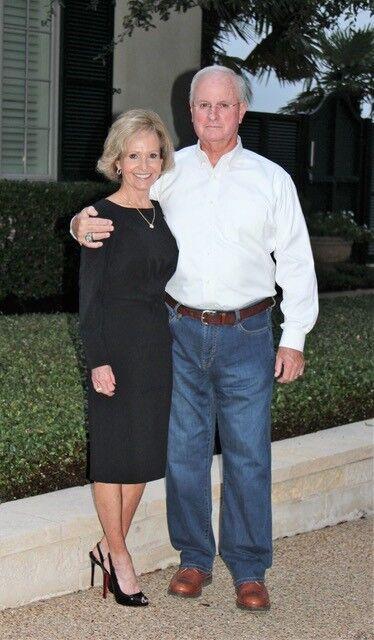

The influence of his grandfather and his dad, as well as his upbringing around the New Mexico athletics scene, were clear from Pat and wife Gail Henry’s very first date.

Though both were students at New Mexico, the pair didn’t meet until Pat’s senior year while working at J.C. Penney during the Christmas season — Pat in sporting goods and Gail in men’s underwear. They attended a Lobos’ basketball game on their first date, but it was what occurred during a post-game stop for hot chocolate that would lead to their nearly 47-year marriage.

Trying to combat the first-date awkwardness, Gail asked a simple question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Pat’s response, which he has no recollection of, had a profound effect on her.

“He said, ‘I want to be the head track and field coach at a major university some day,’” Gail said. “I said, ‘Wow, you already know that?’ And he says, ‘I’ve known that since I was seven years old.’”

The certainty with which Pat expressed his future aspirations drew Gail in.

“He was so confident — that’s what he was going to be when he grew up,” Gail said. “I thought, ‘That’s incredible. I’m going to follow this guy and see if you really can know that when you’re that young.’ He was so confident, and I believed him with every fiber in me.”

Two dates later, Gail and Pat began to discover coincidences that had connected them before they ever met at the Albuquerque department store.

Two years Pat’s junior, Gail realized their parents had attended Albuquerque High School together. Not only that, but she and Pat had also attended the same high school, and Gail knew one of Pat’s younger brothers, Matt.

“It just snowballed from one thing to the other,” Gail said. “Here we are, 48 years later. [It’s] pretty incredible.”

In 1973, soon after they started dating, Pat graduated from the University of New Mexico and took a job teaching and coaching track and field at Hobbs High School, over 300 miles southeast of Albuquerque where Gail still had two years of school left.

The pair had to limit their phone calls to just a few minutes a couple days a week because of the long distance romance, but Gail said they kept in as constant of contact as they could by writing letters daily.

A month into Pat’s job, he returned to Albuquerque to visit Gail for the first time since the move. The person she welcomed back after over 30 days was much different than the one she had said goodbye to.

In the short time he had spent working in Hobbs, Pat had become incredibly serious, Gail said. Knowing he needed to be a mentor rather than a friend to his students and his athletes, Pat had put on what Gail now calls his “game day face.”

“He had to be somebody that they looked up to that they would want to mimic,” Gail said. “He took on that role immediately when he got out of college. It struck him that, ‘The way I want to live my life has to be an example to these students and these athletes.’”

Bringing the Henry family legacy back to Texas

Before becoming a coaching legend, Gwinn Henry was born and raised in Eden, Texas, home to just under 2,000 people and the birthplace of former A&M President James Earl Rudder.

Gwinn spent much of his adulthood away from his home state after leaving his first coaching job as the first football coach at Howard Payne University in Brownswood from 1912-1913.

He returned to coaching full time in 1918 and spent the next five years at the College of Emporia in Kansas before moving on to the University of Missouri, where he served as the head football and track and field coach.

In his nine years in Columbia, Mo., Gwinn led the football team to a 40-28-9 record, prompting the school to erect Memorial Stadium in 1926 after two consecutive Missouri Valley Conference titles. Gwinn then spent the 1933 season coaching the independent professional football team the St. Louis Gunners before he was encouraged to move west.

“For health reasons in those years, they wanted him to move to a drier climate, which doesn’t seem right today but that’s what they did in those days,” Pat said.

Gwinn spent two seasons coaching football and track and field at the University of New Mexico before moving back east to finish his career at the University of Kansas.

But even after all those years, Texas was waiting for the return of the Henry family.

Ten years into his coaching career — and five state championships later — Pat decided it was time to leave his first job at Hobbs High School and move on to the next level: a junior college.

Desiring to “build a program,” Pat knew when then-Blinn College-Brenham President Walter Schwartz called him about a head coaching job, it was the right decision.

In his four years there, Pat coached his men’s team to a pair of championships, sweeping the NJCAA indoor and outdoor titles in 1987. Pat also earned Indoor and Outdoor National Junior College Coach of the Year honors in 1986 and 1987.

Making true on the declaration he had made to Gail several years prior, Pat took a call from then-LSU Director of Athletics Joe Dean and moved east to Baton Rouge.

“When LSU called, it wasn’t much of a decision,” Pat said. “I would have walked to LSU to take that job.”

Pat would go on to lead the Tigers to 27 national titles in 17 years, but he was making history before he even got to campus.

“That was a big step for a Division I school to hire a junior college coach at that time,” Pat said. “That was something that didn’t happen very often, and I was very fortunate. We had developed a team at Blinn, and LSU wanted a team.”

It didn’t take long for Pat to find success in Baton Rouge, as his women’s team won the NCAA Outdoor Championship in his first season in 1988.

The next year, Pat would continue to make history as LSU became the first school in the NCAA to ever win both the men’s and women’s national titles in the same year, repeating the feat in 1990 as well. Under his leadership, his women’s team swept the indoor and outdoor national titles eight times.

But at the end of his 17th season at the helm of LSU’s track and field program, Pat made a surprising choice, bowing out as the Tigers’ head coach to return to Texas and take over at A&M for the 2005 season.

Pat’s decision to leave LSU after nearly two decades and almost three dozen national championships didn’t come as easy as his decision to join the program.

“It was tough,” Pat said. “We had great teams, and we had sustained and had great teams for 17 years, but at that time if I was ever going to make a change, I was in an age where I needed to make a change.”

Prior to Pat’s arrival, A&M had only won one conference championship on the men’s side — no national titles. Pat said it was his mission to change that upon his arrival to College Station.

“A&M had always had some great athletes. They hadn’t won a national championship, but they had great athletes,” Pat said. “They just didn’t have enough of them to have a really good team. That’s not to say anything bad about the coaches that were here prior to me getting here, but I had a different way of doing things and I wanted to bring that with me.”

Gail questioned the move, not wanting to uproot the life they had built in Baton Rouge. Pat said his wife’s hesitancy was his “biggest stumbling block” when it came to making the decision.

“Coaches, we go to school, we’re on campus and we get involved in the community, but not as much as your wife does,” Pat said. “They develop lots of [friendships] that have nothing to do with the university. That’s not the way coaches are. Very seldom do we have lots of friends away from [our] actual institution.”

Gail was a stay-at-home mother for much of her and Pat’s married life, but once their two children got their driver’s licenses, she decided she wanted to begin a career in financial planning.

Finally settled in her career, Gail said she felt defensive about Pat’s eagerness to make the move back to Texas.

“I had been long and strong and going very well with my career, and then he up and wants to move? Well, I had my dukes up,” Gail said. “Now, it wasn’t just his career [that was affected by the move], but he was so positive that this would be a good thing. I wasn’t quite so positive because it was going to uproot me and what I had grown and wanted to do.”

Though she was adamant about not leaving at first, a trip to College Station and a look at the Aggie Network in action sealed the deal for Gail.

After a dinner with then-A&M Director of Athletics Bill Byrne during their visit, Pat and Gail returned to the Hilton Hotel to find three voice messages on the phone in their room.

All three messages were for Gail from local financial planning companies offering to hire her, “sight unseen.”

“That night, my attitude changed,” Gail said. “The next day, I asked more questions and found out about the Aggie Network and the Aggies’ love for Aggies all over this world. I was so impressed and I thought, ‘Okay, there is something to this.’ … I hated walking away from what I had built [in Baton Rouge] and the career I had, but oh my gosh, it was just such a blessing.”

Gail said after experiencing the Aggie Spirit first hand, she had no more doubts about the move.

“Everybody cares about everybody, and it’s easy to care back when everybody cares about you,” Gail said. “This is an unbelievable place … There’s just no other school that’s like this one.”

Pat’s decision to take the A&M job brought him 200 miles southeast of where his grandfather began his coaching career at Howard Payne.

Now in his 17th season at A&M, Pat has led the Aggies through a move to the SEC in 2012, picking up 17 conference and nine national titles along the way.

Learning from his dad and grandfather’s coaching styles, Pat has employed what some may call an “old-school” method to running his programs.

“I’ve always wanted to develop teams. Individuals — sure because great individuals come out of great teams. But I’ve always wanted a track team,” Pat said. “I never wanted just sprinters or just [one] discipline. A lot of universities have let it go that way — they pick specific disciplines they want to be good at, but that’s not the way I want it.”

Leaving his mark on the world

From high school to junior college to Division I, Pat Henry has made it his mission to train up the younger generations, not just in sports but in life.

While some of his athletes pursue sports professionally, there are many more that don’t, and he wants people to end their time in his program “knowing they were part of something.”

“The something is always greater than the self,” Pat said. “If you’re an athlete and you have the opportunity to be on a team, then you learn in the business world how to get along. On a team you have to get along with each other, you have to have expectations for each other, you have to understand the people that you’re working with. I think that transfers over to the real world.”

Matt said Pat approaches every aspect of his job — leading, teaching, disciplining — with kindness and integrity, traits he learned from watching his dad and hearing stories about his grandfather.

“You will never hear a bad word out of Pat Henry’s mouth,” Matt said. “You won’t hear a curse word. A lot of times that might be a way to motivate some people, but not out of Pat Henry’s mouth. That was true with my dad and my grandfather too. I think Pat has been that way more than anybody [in our family] in terms of not losing their composure and treating young people correctly.”

As much as he learned from his dad and his grandfather, Gail said Pat’s personality is something unique to him.

“I think Pat has a gift,” Gail said. “Yes, he learned a lot of it from his dad and a lot of it from his family, but I think God has given Pat a gift.”

With 36 total national titles in his 48 years of coaching, Pat is one of the winningest college coaches with the second-most NCAA Division I championships in any sport. But to Matt, his brother still doesn’t get near as much recognition for his success as he should.

“Of course, I’m prejudiced toward Pat Henry, but if you were to ask who is the most famous basketball coach in the United States, a lot of them will say John Wooden,” Matt said. “But in our sport, if you mention Pat Henry, a lot of people will have to Google the words ‘Pat Henry’ to find out who he is. To me, John Wooden can’t fit in the back pocket of Pat Henry. Pat Henry is the most successful track and field coach of all time in my mind. There have been many other people that have done very good in this sport, but Pat Henry has been very, very successful no matter where he was — at high school, in junior college, Louisiana State University or Texas A&M. There hasn’t been a year where he hasn’t been successful.”

Pat can now find his name in three state sports halls of fame: Texas, Louisiana and New Mexico. However, he said success to him is measured by more than just what has happened on the track.

“You’re given some awards, like being in the Texas Hall of Fame and the Louisiana Hall of Fame and the New Mexico Hall of Fame, and they always ask you about legacy and they want you to talk about legacy,” Pat said. “For me, that’s just something that I can’t control … If I’m happy and my wife’s happy and our athletes and my coaching staffs are happy, that’s all I can worry about.”

Despite all the awards and the accolades, none of it is as important to Pat as the people he surrounds himself with, from his friends and family, to his staff, to his athletes. The people make the journey, and Pat Henry’s journey is far from over.

“He’s going to be in history books,” Gail said. “I think his legacy is going to be … not the success of Pat Henry, but the success of the people that he’s coached … He’s influenced this female or this male, but then it’s been an influence to their spouse, then it’s an influence to their children. He has made so many good people in this world, I’m in awe over him.

“I’m so blessed by what he’s given back to the world. Forty-eight years, and he’s not done.”