At age 15, Macy Toronjo was faced with a choice many don’t make until several years later.

She was too young, she now acknowledges, but due to the very nature of her chosen sport, Toronjo was forced to pick a college to attend.

Toronjo ended up choosing UCLA, where she spent five years as a member of the gymnastics team that won the 2018 National Championship during her tenure.

For Toronjo, a Huntsville native who spent several years training at Texas Dreams Gymnastics in Coppell, the nearly 1,500-mile move from Dallas to Los Angeles fulfilled a dream to compete at the collegiate level, but it wasn’t necessarily a move she wanted to make.

Toronjo comes from a family of Aggies. Her dad, Walter, is Class of 1974. Two of his brothers and their wives, as well as Toronjo’s older half-brother and half-sister, also attended Texas A&M.

Her brother Will, a wildlife and fisheries sciences senior, will be taking over as head drum major of the Fightin’ Texas Aggie Band for the 2021 football season.

But Toronjo didn’t have the choice to continue her family’s tradition and become an Aggie.

She has, however, made her way back to A&M, now serving as the club gymnastics team’s coach and an academic mentor for student-athletes within A&M’s athletic department, but for Toronjo, staying in Texas as a collegiate gymnast was a dream she never got to see come to fruition.

A&M doesn’t offer a varsity-level gymnastics program.

In fact, no Texas university offers a Division I program. Texas Woman’s University in Denton sponsors gymnastics, but the team is a Division II program and isn’t able to provide the same resources as a Division I school.

Despite the lack of collegiate programs, Texas still has a vibrant gymnastics culture, Toronjo said.

“Texas is a huge hub for gymnastics,” Toronjo said. “Had there been a DI team in Texas, I would have just stayed in Texas because I was like, ‘I don’t want to go to a city.’ But I did, I left.”

The state has produced Olympic talent such as gold medalists Simone Biles, Nastia Liukin and Carly Patterson. Mary Lou Retton trained in Texas as a teenager. Two of Toronjo’s UCLA teammates — Madison Kocian and Katelyn Ohashi — trained at the World Olympic Gymnastics Academy in Plano.

Among the eight SEC schools that currently sponsor gymnastics programs, 15 athletes are from Texas — enough for a full roster. Three head coaches also hail from the state.

With over 250 gymnastics clubs sponsored by USA Gymnastics, Texas has solidified itself as a hotbed for the sport, despite the lack of college-level opportunities.

Though she coaches the only NCAA-level program in the state, Texas Woman’s gymnastics coach Lisa Bowerman said the state’s rich pool of talent doesn’t necessarily mean she has an advantage in recruiting.

“Anyone who has been around or knows the sport at all knows that Texas is a hotbed for the sport of gymnastics,” Bowerman said. “That’s why colleges from all over the country come here to recruit our kids, and we’ve got some incredible gyms and incredible athletes here in our state. Just by sheer numbers as well, it’s a very much-loved sport here in our state.

“It is a little bit baffling that there’s only one NCAA program in this state where it is so strong and is so popular.”

Bowerman said while she does have athletes choose to compete for her in order to remain close to their families, Texas Woman’s Division II status puts her at a disadvantage in terms of what she can offer to recruits. While Division I programs have up to 12 scholarships to offer, Bowerman said Division II schools are allotted just six.

“[Division I schools] generally give full-rides, and we do not because of how our scholarships work and how we have to divide them up and combine some athletic scholarship with [academic scholarships],” Bowerman said. “We lose a lot of really strong talent because they can go outside of our state and get a full ride, which we can’t offer.”

The state’s history with the sport goes back to Béla and Márta Károlyi, the former coaches of the United States Women’s National Gymnastics Team who established the Karolyi Ranch in Huntsville in the 1980s.

The Karolyis helped build a gymnastics culture in Texas, said Lauren Porter, a meteorology junior and three-year member of A&M’s club gymnastics team.

“A lot of gymnasts and coaches came here to be around that because the Karolyis used to be the people who decided on the Olympic Team,” Porter said. “Being invited to the Karolyi Ranch — it was a big deal to be near that and having the opportunity to have the Karolyis come and see you.”

Though the Karolyis’ influence on the sport has been marred by recent abuse scandals that led to the ranch being dropped as a USA Gymnastics’s training center in 2018, Bowerman said the love for the sport that lives on today in Texas is still due to the duo’s influence.

“Back in the day, the best gymnasts moved across the country to come to Texas to train with specific coaches and to train in specific gyms because they were having success at the national and international level,” Bowerman said. “I think that kind of got the ball rolling, and it just continued to build from there and became a part of the culture of our state and a sport that was known and loved within our state.”

While the Karolyi Ranch is no longer an active training center for the national team, Porter said the state still has a plethora of clubs to continue promoting its gymnastics culture. Toronjo’s former club Texas Dreams and World Olympic Gymnastics Academy, or WOGA, in Plano are two of the most successful clubs in Texas, and tied for fourth-most Junior Olympic National Team qualifiers among the nation’s clubs in 2017.

“Every gymnast knows the culture of Texas gymnastics. Here in Texas, you see very competitive gymnastics clubs,” Porter said. “We have places like WOGA and a few other places that we see national champions and a lot of Olympians come out of. A lot of your gymnasts who are in the NCAA or the Olympics are from Texas, and that’s where you see a majority of super high-level gymnasts coming out of.”

Despite the deep-seeded culture surrounding gymnastics in Texas, there is another sport that takes precedent in every level from peewee to high school to professional: football.

Porter said the importance of football in Texas led to other sports, including gymnastics, being put on the “back burner” in the early days of athletic departments across the state.

The state’s conference alignment also plays a major role, Porter said, as some conferences have a richer history of particular sports than others.

Of the 24 Division I schools in Texas, four are housed within the Big 12. Only three Big 12 schools currently offer gymnastics programs: Iowa State, Oklahoma and West Virginia, while the University of Colorado at Denver competes within the conference as an affiliate program.

Contrarily, all but four of the 14 schools in the Big Ten sponsor varsity gymnastics as of the 2020-2021 season.

Though there is already a precedent of SEC schools adding gymnastics programs with over half of the conference’s institutions offering the sport, the process of doing the same at A&M is not that simple. Toronjo said she doesn’t anticipate it being a money issue since the state’s gymnastics culture and the strength of the Aggie Network would aid in finding donors.

It’s not a spacing issue, either. A&M’s club team already has a facility in the Student Rec Center, which Toronjo said is better than what most club teams across the country have, as many use gymnastics centers in their local communities to practice and host competitions in.

Rather, Bowerman said it is likely a “matter of priority.”

“I don’t know that in every case it is financial,” Bowerman said. “I’m sure in some it is, but I don’t know if it’s simply a matter of priority for the distribution of resources within athletic departments among other sports that are popular and revenue-generating.”

Since 2004, A&M’s athletic department has looked largely the same.

The last time a sport was added to the varsity level was 1999, when the athletic department expanded to sponsor equestrian and women’s archery. The archery program was dropped in 2004, but the athletic department has continued to sponsor the equestrian team, despite the NCAA recommending it be dropped as an emerging sport in 2014, according to an article from The Eagle.

For A&M to now add gymnastics would take a reshuffling of its Title IX compliance.

For an athletic department to be in compliance with the NCAA’s Title IX legislation, there are three requirements it has to meet: participation, scholarships and other benefits.

According to the NCAA’s website, the participation stipulation requires institutions offer “an equal opportunity to play,” which includes providing opportunities for women and men that are proportionate to the university’s full-time undergraduate enrollment rates for both sexes, demonstrating “a history and continuing practice of program expansion for the underrepresented sex” and accommodating “the interests and abilities of the underrepresented sex.”

In terms of scholarships, the funds must be proportional to both sexes’ participation, while “other benefits” require equal treatment in 11 areas including equipment, access to tutoring, medical facilities and services, recruitment and more.

There is a general misunderstanding when it comes to athletic compliance and Title IX, said A&M associate professor of sport management Paul Batista.

“There’s a misconception that everything has to be equal or identical,” Batista said. “The statute uses the terms ‘proportionate’ and ‘equivalent.’”

Title IX isn’t the only issue that would need to be overcome to expand gymnastics at the collegiate level. COVID-19 has complicated the state of athletic departments across the country, Batista said, causing the elimination of 85 sports programs as of Feb. 15, according to businessofcollegesports.com.

“My understanding is there is no push in the athletic department to expand to additional sports on campus,” Batista said.

Additionally, Batista said there is legislation making its way through the federal courts that could make athletic departments hesitant to initiate change until those are decided.

Batista specifically cited the NCAA’s name, image and likeness legislation, as well as the National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston case, which was heard by the Supreme Court on March 31 but has yet to be decided. The case is brought by former Division I men’s and women’s athletes regarding the NCAA’s restrictions on athlete compensation.

“Everything is up in the air, and it would be foolish to predict what’s going to happen until we know the outcomes of some of this legislation and the cases pending against the NCAA,” Batista said.

Despite the financial repercussions of COVID-19 and the potential legislative changes, gymnastics is growing across the nation. Long Island University added the program for the 2020-2021 season, joining a list of 62 NCAA Division I women’s gymnastics teams that competed last season.

Bowerman is a member of the Collegiate Gymnastics Growth Initiative committee, which is a part of the Women’s Collegiate Gymnastics Association. Bowerman said the committee is working toward two primary objectives: raising funds to potentially offer to a university to help get a gymnastics program added and educating administrators on what gymnastics would bring to their respective universities.

“Texas has been a target for a long time within our sport. I don’t know what it’s going to take [to expand the sport in Texas],” Bowerman said. “All of those things are being researched and looked at and done extensively, but what it’s actually going to take for a university to pull the trigger so to speak and make that decision to add, that’s the question that we need an answer to that we haven’t found yet.”

Although she acknowledges the process of expanding the sport on a collegiate level hasn’t happened as quickly as she and many of her colleagues have hoped, Bowerman said she is still optimistic that one day that could change.

“What is being done is working, it’s just slow. I don’t know if at some point that will ever change, or if we just have to continue to grind at it and be patient and wait for the things to line up where there is an administrator who sees the value and wants to go down that path at another school,” Bowerman said.

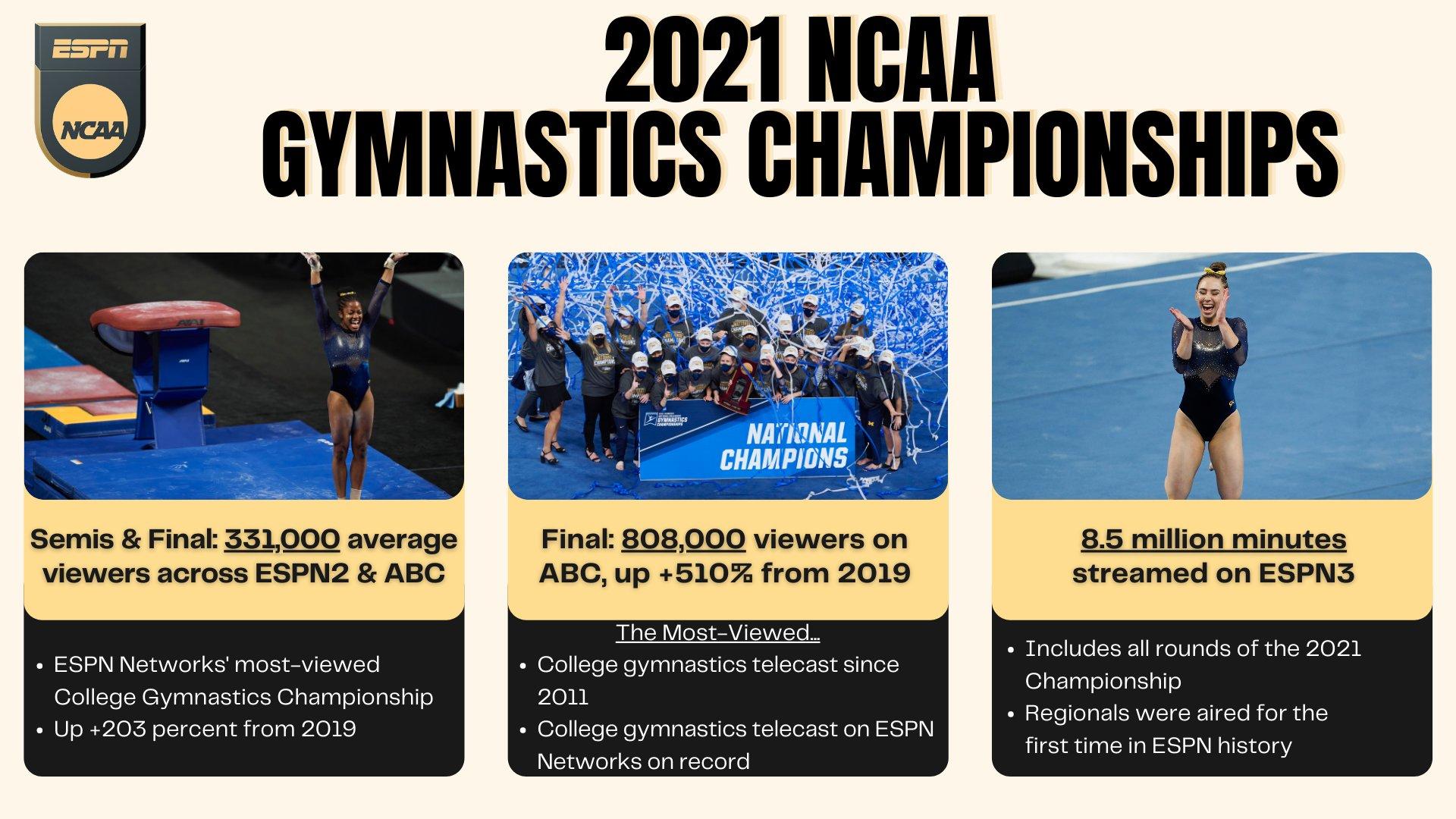

The recent women’s gymnastics national championship meet may be proof that Bowerman’s optimism isn’t unfounded.

Texas Woman’s University hosted the 2021 National Championship at Dickies Arena in Fort Worth April 16-17 and is scheduled to do so for the 2022, 2023 and 2024 championship meets.

The event was broadcast on ABC for the first time in its history, returning record ratings with 808,000 viewers for the April 17 finals, which was a 510 percent increase from its 2019 viewership, according to ESPN. The broadcast is now the most-viewed college gymnastics telecast on ESPN Networks on record.

“I think all of those things kind of add to the excitement around our sport, and in addition to that, with it being an Olympic year, the Olympics always hype everyone up about our sport and remind everyone how incredible our sport is,” Bowerman said. “Hopefully the combination of those two things will be a step in the right direction in creating some buzz and getting more people excited about our sport.”

Bowerman said she thinks it will take just one major institution in Texas to add gymnastics for others to follow.

“There are times that it can feel hopeless, but I also know that what our sport offers to any university is incredible and I believe strongly in that,” Bowerman said. “We’re not going to stop working toward that ever probably, and I think it’s just a matter of time before one larger university in the state adds and then someone else sees their success and it can hopefully domino effect and grow from there.”

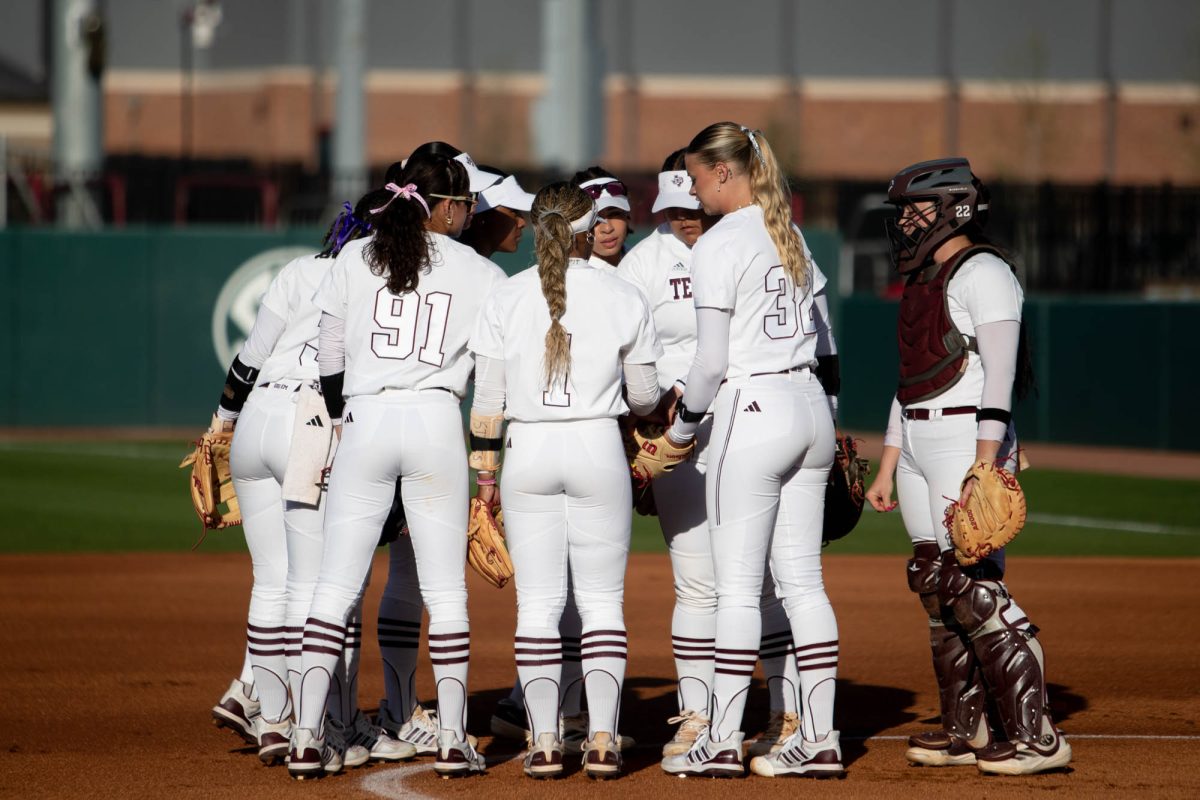

With the increasing popularity and success of club gymnastics teams in Texas — A&M’s club won the National Association of Intercollegiate Gymnastics Clubs Championship in 2019 — Porter said it is only a matter of time before a university’s administration takes notice.

“The more we have people joining the club teams, the more I think schools will see that it is a popular sport here and there is opportunity to grow that,” Porter said. “A&M being a part of the SEC now, I do foresee that eventually being an option because the SEC does have a lot of phenomenal gymnastics programs with a history of it. It just might take a while for our university to see that, and unfortunately there’s nothing that the club teams can do other than gain recognition.”

Although there is not yet an end in sight to the work left to do to expand gymnastics in Texas, there is still plenty of interest and passion surrounding the potential growth of the sport on the collegiate level.

Four-time Olympic gold medalist Simone Biles, a Houston native, tweeted in 2018 to express her support for the University of Houston’s gymnastics club and her hope that it will eventually move up to varsity level.

“If UofH (University of Houston) gymnastics team got NCAA approved in the future, I’d consider coaching gymnastics after my career,” Biles said.

Regardless of the push to expand the sport to the collegiate level, Toronjo said college club teams still hold a significant importance for the sport.

Stories of abuse have overshadowed the sport in the past few years, as allegations against former USA Gymnastics national team doctor Larry Nassar have exposed a long-standing abusive culture in professional gymnastics.

Toronjo, who said she experienced emotional abuse at the hands of her Texas Dreams coaches, also said the abuse she experienced caused her to harbor negative feelings toward the sport she once loved.

“It’s like being abused by your family,” Toronjo said. “You don’t want to go back — you don’t want to go into a gym because you get sick to your stomach, and that feeling of fear is so crippling when you’re so young … There is mental and emotional abuse in every single sport when you reach a high level; however, the difference between gymnasts is that you have to start when you’re young. You have to start when you’re at least five.”

The pressure she and her coaches placed on her to succeed at a high level became toxic, Toronjo said.

“This is a sport of failure — you start at a 10 and they just deduct everything that’s wrong with you,” Toronjo said. “This concept of being perfect, it doesn’t exist, and when you’re 12 you don’t really understand that.”

College clubs provide a place for athletes to compete without the pressure of pursuing “perfection,” Toronjo said.

“It gives people the space to find their joy again,” Toronjo said.

That joy is something Toronjo said she has yet to find again, though some of the club’s members have been successful in rekindling their love for the sport after going through similar situations.

“With everything they went through, they came back to the sport and maybe they’re not doing as hard of skills. That’s OK,” Toronjo said. “They’re doing it because it’s fun and they love gymnastics. That’s something I honestly have not felt or been around in a very long time.”

For Porter, who trained at APEX Gymnastics in Leesburg, Va., A&M’s club team gave her a sense of familiarity despite being over 1,000 miles from home.

“Gymnastics has always been an easy place for me to make friends,” Porter said. “I’ve done it my whole life, and in high school I didn’t do much in school because as soon as school was over I had to go straight to gymnastics almost every day. I knew by joining gymnastics I could easily make friends, I could continue doing the sport I love, and it was also a place for me to train and get energy.”

Her teammate, bioenvironmental sciences junior Kaylee Connolly, had never done gymnastics prior to stepping foot on A&M’s campus, but has since found a nucleus of support and camaraderie through A&M’s club.

“It’s like a small little family,” Connolly said. “Everyone there comes from different gymnastics backgrounds, but when we’re all in the gym at the same time, it’s great. I love the program — it’s so supportive. We’re all grateful we have the opportunity to continue gymnastics in college at that level.”

Despite the special place the club team holds for them, the members still have a desire for the club to grow to varsity level.

“I wish there was something we could do to make NCAA happen, but unfortunately, it’s all up to the authorities,” Porter said. “As much as it stinks, it is what it is. But the more we get recognition for club teams in the state of Texas, the better it’ll be.”

After making the 1,500-mile move to Los Angeles to pursue her collegiate career, Toronjo is finally making Aggieland her home, though not in the way she imagined growing up.

But as special as it would have been for her to compete in her home state, she said the expansion of the sport at the collegiate level, whenever the time comes, will be “huge.”

“It could have been something really special, and who’s to say ‘could have.’ Maybe it will or could be something special,” Toronjo said. “It would be really awesome to see because it would have been a huge movement for the sport. The sport is in a new cycle right now, it’s changing … and the culture is shifting to more joy.”

Lack of in-state NCAA opportunities for Texas gymnasts ‘baffling’

May 5, 2021

Photo by via @mtoronjo on Instagram

Texas A&M gymnastics team coach Macy Toronjo competed as a Division I gymnast at UCLA for five years.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$1965

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!