Ron Carter’s home burned for two hours while he and his family vacationed in Alaska in 2013. A fire chief’s phone call waited at the hotel, but Carter’s first question was not about the house.

“I asked them, ‘My Aggie Ring’s back there — if you could find it, please try to find my Aggie Ring,” Carter said.

Twenty-seven hours by plane, train and car brought Carter, Class of 1974, and his family back to College Station. His Aggie Ring was eventually found alongside his wedding ring — both burned, encrusted in ash and barely recognizable. Two weeks later, however, the ring was restored to its luster by a careful, handcrafted process designed to repair or replace an Aggie Ring in any condition and age.

To Carter and the former students who send their rings to Balfour for repairs, the process seems effortless — rings worn down by a lifetime come back clean, polished and exactly as requested. To the craftsmen who make it happen, however, an Aggie Ring repair is built on a lifetime of experience.

Start to Finish

An Aggie Ring passes through Balfour’s Austin factory every day of the year, explains David Collier as he walks through the factory floor. Collier, director of manufacturing at the Balfour factory, said the factory works on over 100 Aggie Ring repairs and replacements a day. These numbers continue to grow with the student population, a fact that Donna Hebert, who stands at the beginning and end of every repair order, understands better than most.

Hebert inspects every repair order that passes through the factory, and no former student receives their ring again without her approval of the restoration. She moved from Massachusetts to Texas with the factory when it moved in 1997, and has worked on rings for almost 30 years.

“I just want to make sure they are the best rings [a student] can have, so they can really proudly display their accomplishments and tell everyone, ‘This is a Balfour ring,’” Hebert said. “That’s basically what I want, to make sure [the ring is] exactly what they want, and that it’s the best that it can be.”

Rings arrive for repairs either from the Association on a former student’s behalf, or directly from a former student. Large envelopes contain the damaged rings and repair requests. Hebert slides a ring out of one envelope — the surface is almost completely worn away across its dull surface.

“Obviously this ring is very old, very worn. So that’s what I’m going to write down … Look at the palm side. Obviously there’s no pebbling so I write ‘no pebbling,’” Hebert said as she turns the ring in her palm. Its accompanying paper reads “Class of 1964.”

Dents, nicks, worn carvings, lacquer and dirt — Hebert lists every part of her checklist as she examines several rings and writes her observations on the ring envelope’s back. Many rings come in for repairs with an interesting note — do not repair, at least not fully. Despite its condition, the ’64 ring’s owner wrote a very specific request: “Do not refinish or re-pebble.”

“We do as little as we can, only what they want,” Hebert said. “We don’t take care of everything because a lot of them, they like that old look, they like that scratched look, they like that worn look.”

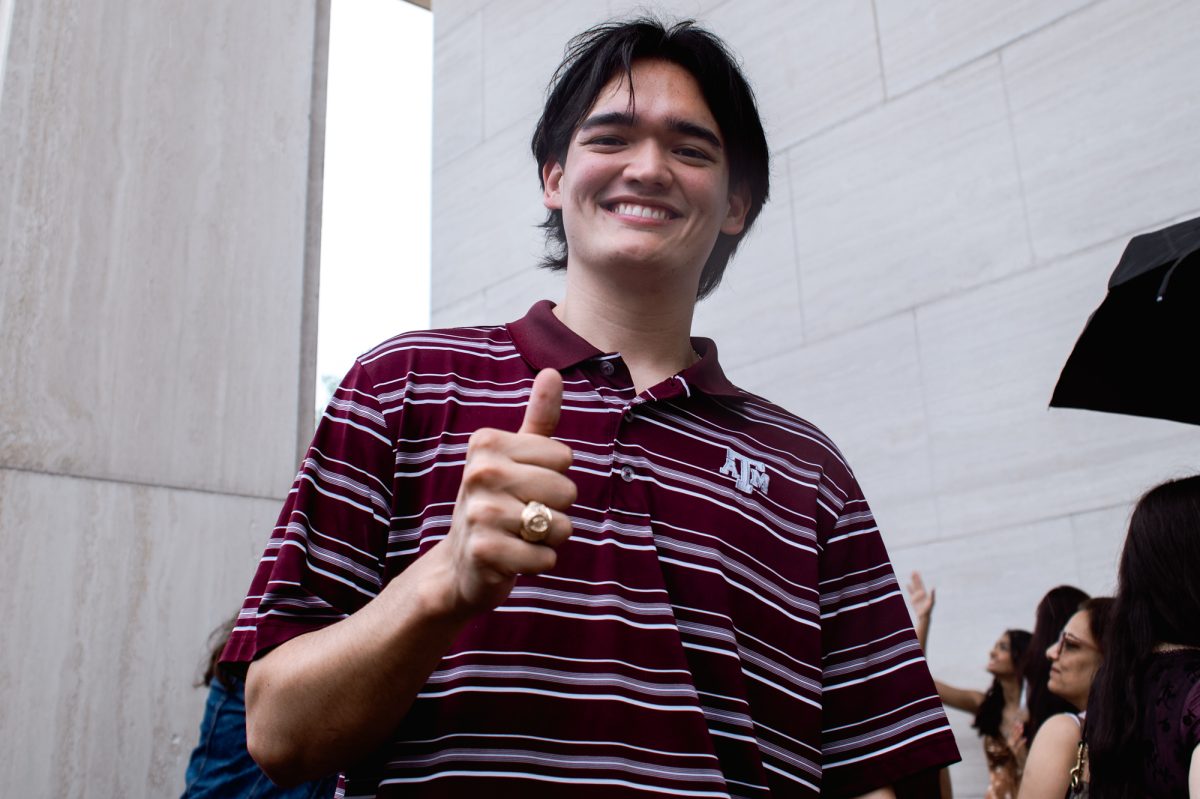

Aggie Rings and Hebert’s notes then pass on to one of several craftsmen, depending on the former student’s requests. Many request a resizing and end up in front of Eric Amaya, who arrives at the factory most mornings at 4 a.m. to cast the gold for new ring orders before shifting to resizing in the afternoon.

Amaya reads Hebert’s notes on the ’64 ring and places it on a thin rod that gradually thickens to a larger base. Rings are resized by breaking them and welding new gold into the gap; Amaya hammers the ring down the rod to open its back end, but the ring begins to come apart in several places. This can happen to older rings, Amaya explains, because past casting techniques made the ring from three pieces instead of one.

“A lot of these older rings were made in three pieces back when they were made in Attenborough, Massachusetts,” Amaya said. “So sometimes I’ve actually had a ring where I just hit — barely tap it — and it fell apart into three pieces.”

Collier said the owners of such rings have two options — continue with the resizing and risk a complete break, or keep the size as is. If a complete break does happen and it can’t be salvaged, a new ring is cast.

New Gold, Same Tradition

Tom “Ike” Morris, Class of 1933, walked into the Association when he was 102 to order his third Aggie Ring. His life story weaves in and out of the A&M history most students call tradition — he waited tables with James Earl Rudder, hitchhiked home with E. King Gill and helped set the Aggie Ring’s strict order requirements. His first ring cost $16.50.

“The Aggie Ring opens up a path for trust and future friendships,” wrote Morris in an email. “The ring bonds all Aggies together.”

The ’33 eagle and shield mold that re-cast Morris’ ring rests in one of several trays where Balfour keeps previous class year molds. The molds made from these base designs are injected with hot wax to create a wax ring that is eventually used to cast a gold counterpart.

Despite Morris’ longevity, his was not the oldest re-order on record — a few rows down from his ’33 mold lies a Class of 1925 eagle and shield.

Lifetimes of Experience

Billy Lancaster walked into Balfour’s factory hoping to make some money for his wife and children as a seasonal welder, but 38 years and several positions later, he handcrafts Aggie Ring restorations.

“I was young but I was married and I had kids so I had to have a job — I didn’t miss any work so they kept me. I was supposed to hit the road, but they kept me,” Lancaster said with a laugh as he pulled out an envelope, read Hebert’s notes and examined the ring. Despite a slight tremor in his hands while they rest, his actions are smooth and quick as he works on the ring in front of him.

Lancaster is one of the few craftsmen in the factory who can hand carve individual symbols into a ring. A few letters, the class year or re-engraving the eagle and shield are sometimes done if a former student requests it, but Lancaster said extra care is always taken.

“Hand engraving is like handwriting,” Lancaster said. “They have a certain script, a certain design, that you’re supposed to do the exact same way, but some people make it skinnier, some people make the lines deeper or wider or thinner.”

Right across from Lancaster is Leon Mercer’s workstation. Mercer holds two distinctions — he is the longest-working craftsman at the factory with 47 years of employment that started in Massachusetts before moving with the factory to Austin. He is also the oldest.

“I’m 78 years young,” jokes Mercer as he takes the ring from Lancaster. Mercer smooths, cleans and waxes the ring repairs. After the previous restorations, the ring’s sides are typically sharp enough to cut the wearer, and Mercer must dull them to avoid wearer injury. Despite the ring’s edges and the heat that dulling and polishing generates, Mercer only began wearing thin plastic gloves a few years ago to better stay clean.

“It’s the feeling you’ve got to have, and with your fingers you get that feeling,” Mercer said to describe why he doesn’t use finger guards.

The Final Cut

Lancaster and Mercer send the rings to get re-antiqued or to have diamond repairs if requested before they end up back at Hebert’s desk after two to three weeks. The ring returns to its owner exactly as they requested it — some look completely new, while others still showcase a lifetime of wear. For Carter, the work done on his Aggie Ring after the fire made it look new again.

“When I got it I just couldn’t believe it,” Carter said. “I thought some of it would have melted down, but it almost looks like the day I got it. I was just so ecstatic to see what they could do with that ring, because it was charred black.”

Carter’s restored ring again joined those of his son and daughter as symbols of a time on campus that they will always remember.

“It’s a lot of work to get an Aggie Ring,” Carter said. “It doesn’t come cheap. It’s a lot of work to get there, a lot of hours, a lot of classroom, a lot of course study, and it’s one of those things you drive through because once you know you got there you know you — you’re pretty well rounding third base heading for home because you only have another two semesters or so to finish out.”