From reports on covert operations to recipes for invisible ink, more than 11 million pages of records from the United States Central Intelligence Agency are now available at the click of a mouse.

Under the automatic declassification provisions originally put in place by an executive order during the Bill Clinton administration, agencies like the CIA are required to declassify nonexempt, historically valuable records that are more than 25 years old. As of January 2017, these records from the CIA Records Search Tool, or CREST, have been made available to view and download on the agency’s website.

According to associate professor of history Jason Parker, when the CREST database was originally created, it was only accessible on a specific computer terminal at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

“It was already kind of a leap forward some years ago when, in the national archives, they created a computer — it’s not online, it’s a dumb terminal — but it’s a database, essentially, of declassified CIA documents,” Parker said. “But you have to be there physically to do it.”

Parker said while the agency’s motivations behind the online release are unclear, it is possible that the decision to make the CREST collection more widely available may represent an attempt to create a greater sense of transparency at a time when secrecy is often met with retaliation.

“This latest move, I don’t know quite what to make of because the only thing I can sort of surmise is that in the age of WikiLeaks that it was better to sort of get out ahead of it,” Parker said. “I don’t know if that will be enough to prevent embarrassing disclosures of various kinds in the future, but I like to think it’s because the historic government tendency towards too much secrecy maybe is swinging the other way towards less. It’s a real departure from past practice.”

According to associate professor and university archivist Rebecca Hankins, the movement toward greater accessibility of government records has been gaining momentum, with individuals from a wide variety of fields leading the charge.

“There’s been this whole movement to open access,” Hankins said. “Historians, archivists, librarians, people in political sciences, a lot of the humanities and the sciences for that matter have been pushing for government data in all of its forms to be made accessible.”

Senior Lecturer in Public Service Administration Danny Davis said another possible factor in the CIA’s decision was the fact that the modern state of international affairs has proven to be so drastically different from the image of the world displayed in old CIA documents.

“The world’s changed a lot,” Davis said. “In 1980 we were preparing to fight the Russians. You had nuclear deterrents, mutually assured destruction was the doctrine, all those different things. The world has turned. So I’m assuming, based on the world’s new situation, the authorities are willing to release documents that do not bear on current American operations or policy. And I’d assume transparency is part of the reasoning behind the release policy.”

While the provisions for declassification state that records within the specified window of time become declassified automatically, Davis said documents containing particularly sensitive information must inevitably be made exempt from the declassification process.

“These documents are automatically declassified unless appropriately exempted under the guidelines of the executive order, so obviously for national security if they need to keep something under wraps, they can,” Davis said.

According to Hankins, having access to previous records can help create a more comprehensive understanding of agency involvement in historical events.

“The only thing is to fill in some of those gaps in the knowledge and this is what you find out,” Hankins said. “Your understanding of things is changed and now there needs to be this whole new understanding of a particular incident or activity because now you have this further information that now is saying this is what really happened.”

Parker said while the greater accessibility of CIA records is useful for understanding agency operations, there is always the possibility that key information may be missing.

“It’s a net gain, but we would be wise to be suspicious of whether it’s the whole, complete picture,” Parker said.

Taking this into account, Parker said the online publication of the CREST collection could still prove useful for future research.

“I’m curious to dive in and see what there is,” Parker said. “My next project might draw on some of that stuff and I know that’s true of most of us who study post-war international history, so it’s another potentially great asset to have.”

CIA publishes historical records collection online

April 5, 2017

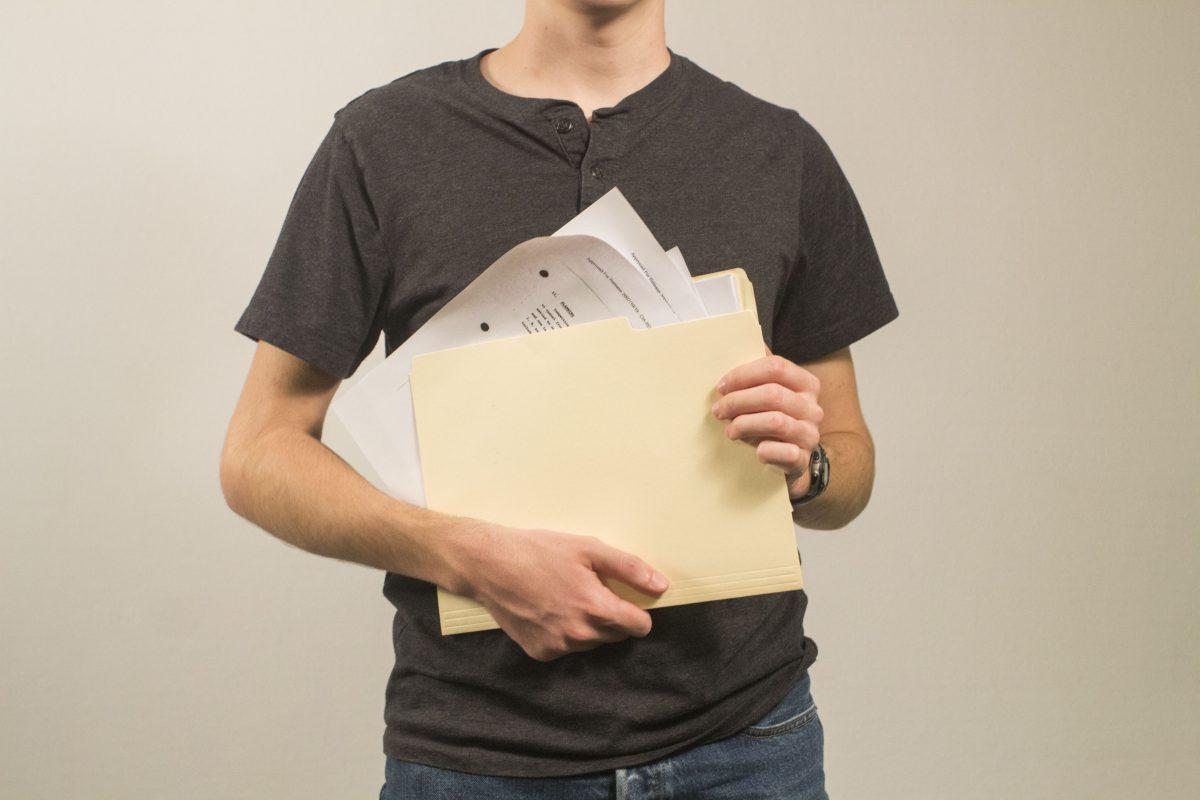

Photo by Photo by Alexis Will

The available documents date back to the CIA’s foundation after World War II and could prove useful for researchers looking into the history of agency operations.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover