Texas A&M researchers studied the long term environmental impact of Hurricane Harvey, including the distribution of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

When Hurricane Harvey made landfall in August 2017, it brought with it more than 64 inches of rain down on the Houston area alone. The excessive rainfall caused massive flooding across the city and brought destruction on homes, businesses and schools. While the country has rallied around Houston and other cities affected by the 2017 hurricane season one, particular threat still looms: pollution.

During the storm, wind and water damage facilitated the spread of chemical pollutants across Houston. The longevity of the floodwaters only exacerbated this issue.

In September, The New York Times reported that more than 40 sites dumped millions of pounds of hazardous materials into the air and water in the wake of Harvey. These pollutants redistributed across Texas by wind and flooding from Harvey are a public health concern, according to A&M researcher Jennifer Horney and her team. In a study released on Feb. 8, Horney’s team concluded there is an increased likelihood for coming into contact with dangerous, potentially carcinogenic pollutants.

“So we’ve been working for about four years with some environmental justice communities in Houston around issues related to inadequate stormwater infrastructure and concerns that they had about environmental health and being exposed to contaminated soil or water in their neighborhoods,” Horney said. “After Harvey they actually asked us to come to the neighborhoods and do some sampling. They were concerned with all of the flooding that contaminates from nearby industrial sites or other potential contaminated sites would have washed into their neighborhoods.”

Horney and her associates conducted their research in the Manchester neighborhood of Houston, a region of the city deemed an environmental justice neighborhood due to its proximity to industrial sites and refineries. Already a area facing potentially hazardous levels of pollutants, the redistribution by Harvey may mean even more public health problems going forward for Manchester and communities like it.

One kind of environmental contaminant Horney said she and her team were concerned with are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which have been determined by the EPA to be dangerous.

“The EPA has designated sixteen priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as priorities because a subset of those could potentially be carcinogenic and so we were primarily interested in those because the sources of PAHs are usually from combustion or from things related to oil and gas and obviously Houston has a lot of that potential for those types of exposures,” Horney said.

Robert Korty, associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences, said the brunt of the long-lasting damage to people and property from Hurricane Harvey will be a direct result of flooding.

“With Harvey, we had the first major hurricane to make landfall on the United States since 2005,” Korty said. “I think what really elevated it to the next level of catastrophe, and what it will really be remembered for, is the flooding that came in the days after the hurricane made landfall all over Southeast Texas. The water is increasingly something that we’re very worried about, the amount of water that’s coming out of hurricanes and the amount of flooding that results.”

Korty said one of the contributing factors to Harvey’s immense destruction was the density of population of individuals in the Coastal Bend region.

“We’re always going to have to deal with hurricanes, and I think there are two things that give us concern that the impacts that we’re going to see from hurricanes are going to continue to be worse in decades ahead than they’ve been in the past,” Korty said. “The first of those has absolutely nothing to do with hurricane intensity and it’s really the growth of the population and the amount of coastal property that exists along the United States and elsewhere in the tropics. There are simply more people and more things in the way.”

Horney and her team’s research concluded there was a transportation of environmental contaminants after Harvey.

“What we found is that based on some sampling we had done about nine months before Hurricane Harvey contaminates were located in different places, so we did believe that contaminates had been transported by the floodwaters because the levels were different and the contaminants were different in different locations,” Horney said. “We were also able to demonstrate that the source of the contamination both before and after Harvey was primarily from combustion.”

Harvey’s harmful legacy

February 22, 2018

Photo by Alex Miller

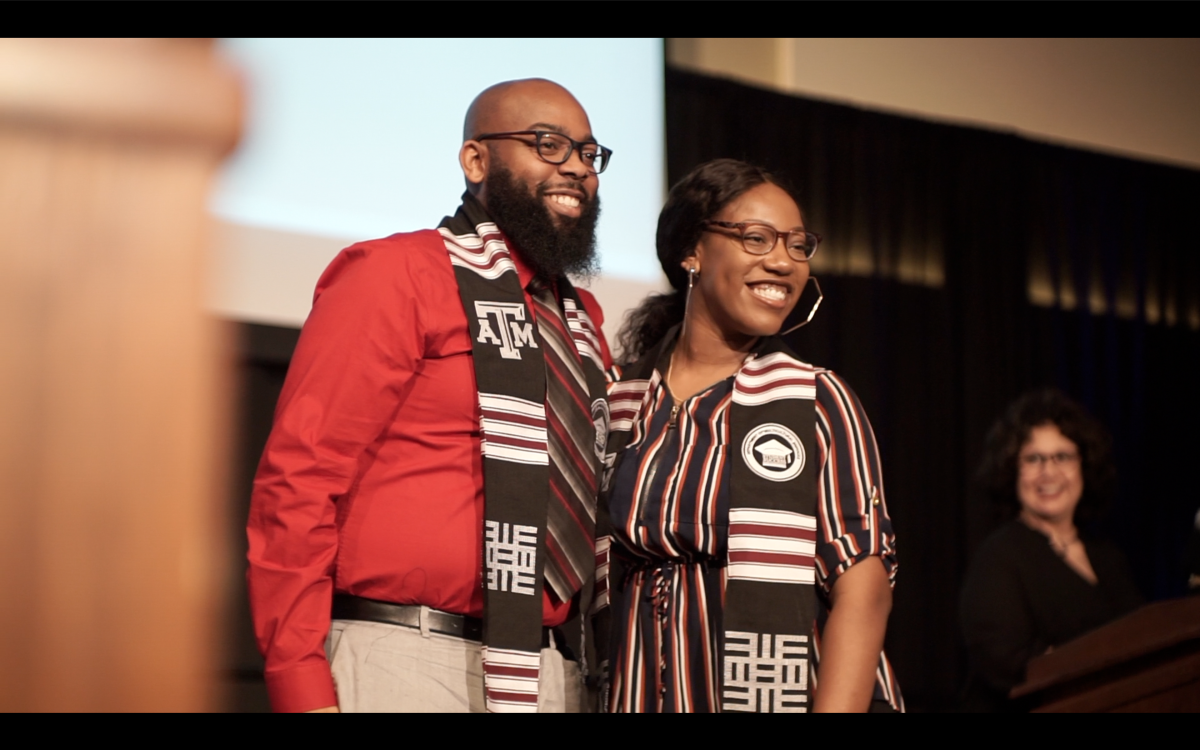

John Jones, Class of 2002, organized a group of around 50 people from the Bryan-College Station area, including a dozen Texas A&M students to help flood victims in Houston of Hurricane Harvey.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover