Over winter break, the yellow bikes that became notorious for showing up on sidewalks and in trees around Bryan-College Station were replaced with teal bikes from another source.

Late last semester, Texas A&M terminated its contract with bike-share vendor ofo and turned to VeoRide as a replacement. The university cited ofo’s poor handling of customers and customer-support issues as reasons for the switch.

The logistics of bike-sharing on campus and in the surrounding city of College Station have proven to be complex to meet campus, user, city and vendor goals. A&M’s Transportation Services and city officials have acknowledged the different standpoints of each party, but both said there is common ground to make a bike-share program productive.

The unsuccessful ofo experience also offers lessons to the new vendor. Veoride’s service will function in much the same way ofo’s did — the rider will download an app, scan a QR code on the bike and lock it in a designated area after the trip. Even with problems, ofo bikes filled a need. Since being introduced midway through the spring 2018 semester, ofo has racked up more than 39,500 registered users in B-CS who have collectively taken more than 500,000 rides, according to a university press release.

The bike-share program was implemented to reduce the number of bikes left behind on campus, said Transportation Services alternative transportation manager Ron Steedly. Standard university procedure is to collect the bikes, hold them for 90 days and notify their owners if possible. If a bike remains unclaimed, it is then sold, but the high costs of constantly impounding and storing bikes demanded a new approach.

“We had an abandoned bike problem,” Steedly said. “With campus growing like it is, I can’t expand bike parking; I’m kind of landlocked.”

The main solution was to introduce a bike-sharing system so more people could use a bike maintained by someone else, Steedly said. While ofo bikes served their intended purpose, both the city of College Station and frequent ofo customers have voiced their complaints about poor ofo customer support.

“They don’t respond to anything,” said university studies sophomore Jose Rueda, who tried to get in contact with ofo last semester when he noticed higher prices. “From the moment they first raised the rates, I’ve sent them probably 10 emails. They have not responded.”

Rueda said his prices went up from 50 cents an hour to $1.50 an hour, while his friends’ rates remained the same. Aubrey Nettles, special projects coordinator for the city of College Station, said the city had concerns with ofo and a lack of city bike-share regulations. When the yellow bikes showed up overnight in March of 2018, the city of College Station did not know about the bike program’s implementation, Nettles said, adding the city was “not aware, not consulted.”

In response, a city ordinance was passed in August requiring any dockless bike-share company operating within College Station to adhere to certain regulations.

“The ordinance allowed us to intervene,” Nettles said. “The city had no recourse. We did not have a seat at the table. Now we do.”

The city revoked ofo’s permit to operate on Oct. 12, then reinstated it on Oct. 26. The permit was revoked due to various infractions of the city ordinance, notably ofo’s loss of general auto liability insurance for vehicles used to distribute the bikes. An ofo representative who was repeatedly contacted for this story has not responded.

Business administration freshman Will Othon, a former frequent ofo rider who purchased a semester riding pass, stopped because of poor service.

“A lot of times I use bikes they’re in pretty bad shape, so that’s why I stopped using them,” Othon said.

With no car or bike in College Station, Othon said he bought the semester pass with the intention of using ofo to get around. Now he prefers the bus system.

“It’s more reliable with a time table,” Othon said. “When you’re using an ofo, you never know if there’s going to be one outside your class.”

Issues aside, ofo certainly excelled in one area — data collection. With a few clicks of his mouse, Steedly is able to analyze trips for patterns and trends. One map showed just main campus, with yellow, orange and red lines of various intensity, indicating the most frequently travelled routes taken by ofo bikes. Steedly said this information can help the university put their dollars toward maintaining the sidewalks and streets that cyclists are already taking.

“There was no way of knowing that before,” Steedly said. “I can better plan the infrastructure budget to meet needs.”

A&M isn’t the only entity benefitting from a bike share program in town. Both Steedly and Nettles said more mobility options allow more opportunity for local retailers, improve the fitness of those riding the bikes and cut down on traffic.

“The biggest pro is that they reduce traffic congestion, more cars off the roadway,” Nettles said. She also noted that the city has invested a lot in sidewalks and trails. “To ensure they are utilized is fantastic,” Nettles said.

At the city level, Nettles and senior program manager Venessa Garza works with Steedly on matters related to dockless bike-sharing. While the city and the university had different perspectives on the main benefits of bike-sharing, both said management could be improved.

“The program itself, I don’t think there is a con,” Garza said. “It comes down to how it gets managed and how the users use the bikes. If they use it poorly, it gives the program a bad name, but hopefully it’ll outlast that.”

According to the city’s ordinance, all dockless bike vendors operating in College Station must accept responsibility to curb bike misuse.

“The city has taken the position that if a bike is left by a student, it is the vendor’s responsibility to change the user’s behavior,” Nettles said.

This can take the form of a fine, or even prohibiting the user from using the service. This is great in theory, but Steedly and Nettles said ofo failed to change user behavior. “Ofo is too chicken to fire [users],” Steedly said.

According to a June press release from the city of College Station, only 2 percent of rides are “non-compliant.” These are the bikes that end up outside of the designated geofence, not properly locked, or stuck in trees. But at 3,400 noncompliant rides, there’s a visible community impact.

“This is some people’s only way of getting around,” Nettles shares. “The bikes are resources for visitors as well. I would hate to see it go away for bad behavior.”

The city of College Station lists “poor customer response or service” in the ordinance as a potential reason the city might revoke a vendor’s permit to operate. The response and customer service complaints, however, can be a lesson for this year’s VeoRide implementation. “We didn’t know what to look for a year ago,” Steedly said.

In the new year, all eyes will be on VeoRide to meet expectations.

“Retail, health, sustainability, less traffic, all those things are byproducts to me,” Steedly said. “I just want to get people places in a cost-effective way that works for them.”

Rise and fall of ofo offers lessons for VeoRide bike-share program

January 16, 2019

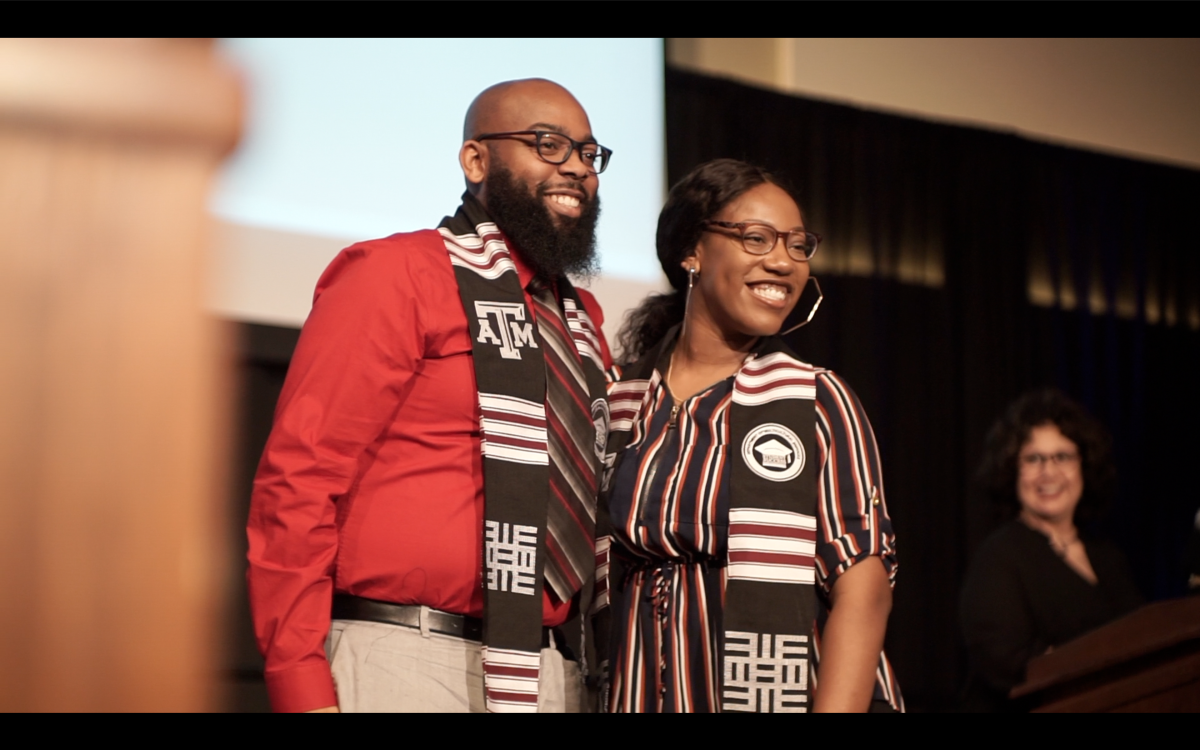

Photo by Photo by Cassie Stricker

A truck hauling dozens of VeoRide’s turquoise bikes drives between the Memorial Student Center and Cain Garage on Tuesday.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2065

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover