Fifteen years ago a group of Texas A&M researchers and their students welcomed CC into the world — the first cloned cat.

CC’s birth marked an important milestone in cloning, and now A&M researchers are exploring new areas of cloning, looking to improve animal and human life. A&M is working to make animals that are more productive on less land by genetically engineering animals with enhanced characteristics.

Mark Westhusin, professor of veterinary medicine and biomedical sciences, said his team’s research uses living bioreactors, an apparatus that supports chemical processes within a living organism.

“We have genetically modified goats that produce malaria vaccine in their milk,” Westhusin said. “One goat is estimated to be able to produce 8 million doses of the vaccine in a lactation period, or year.”

Veterinary physiology and pharmacology professor Charles Long played a key role in CC’s cloning and currently researches early embryonic development and strategies to feed a growing world population.

“The genetic engineering part comes about because clones are genetically identical to the donor animal,” Long said. “They don’t have any kind of improvement over the original. So, when we start thinking about genetic engineering in terms of what we do in our lab we are trying to take what characteristics nature gives us in this breed of cattle and apply them to this breed of cattle, for example.”

A more direct result of cloning research takes place in the department’s embryonic development research.

“[Clones] had all kinds of little things that weren’t unusual, but they were more common in clones than what we would see in normal births,” Long said. “The cloning really led to us investigating those interactions of the sperm and egg and how the embryo is altered by its environment. That all stemmed from trying to understand why clones aren’t always normal.”

Understanding how environments affect embryos is a growing concern for the human population, according to Long, as assisted reproduction practices grow more popular among people.

“Approximately 1 to 2 percent of all babies born in the United States now are born through assisted reproductive technologies,” Long said. “Because of the prevalence of those kinds of offspring being born it is important for us to really understand how the embryo reacts to its environment when it’s outside the mother.”

Long hopes this research will reveal whether or not embryonic environment exposures have long term effects on diseases in offspring.

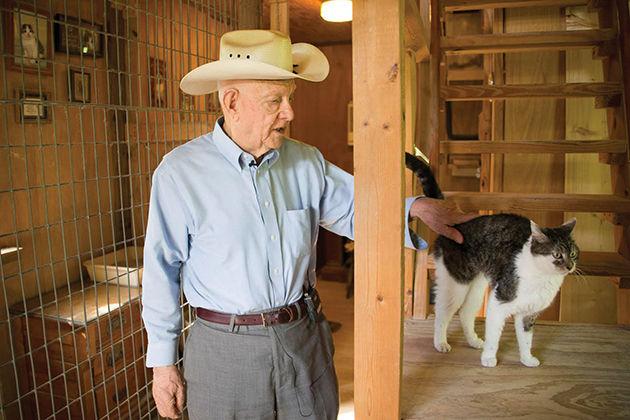

Duane Kraemer, the researcher who conducted CC’s embryo transfer and now acts as CC’s caretaker, said CC spends her time in the Kraemer’s backyard with her 11-year-old offspring. For Kraemer, research after producing CC has included developing an oral contraceptive for wild hogs.

“The wild pigs do a lot of damage,” Kraemer said. “Being a reproductive physiologist, and wild pigs being a big problem I decided that would be something we ought to work on.”

The contraceptive would be placed in feeders that only pigs can eat from to make sure no other animals get into the feed. Kraemer said the oral contraceptive his research team and other departments at Texas A&M are working on is a more humane alternative to the blood thinner recently approved by the Texas Secretary of Agriculture for killing wild pigs.

“It’s not a pretty sight — the death that they experience with that,” Kraemer said. “So a lot of people are objecting to it.”

Research conducted by Texas A&M has certainly changed since CC came into the world, and the researchers who worked to produce her say these changes have been an improvement.

“Our research has always been driven by trying to improve the lives of animals and humans,” Westhusin said.

A&M cloning seeks to improve human life

April 25, 2017

Photo by Provided

CC the cat has helped A&M researchers understand early embryonic development.

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2790

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover