The need to collect ocean soil samples is sending A&M researchers across the globe. The latest expedition sent researchers to Sri Lanka, where samples joined the large collection of rock drilled from the floor of the world’s oceans, located just off Discovery Drive.

The collection’s size is the result of the National Science Foundation’s decision to fund the International Ocean Discovery Program, IODP, in 1984. Through the international program, various science organizations have the opportunity to send researchers aboard the JOIDES Resolution, a scientific drilling ship manned by 100 people that collects data world-wide.

The end location for most samples collected in these voyages is the Gulf Coast Repository at A&M.

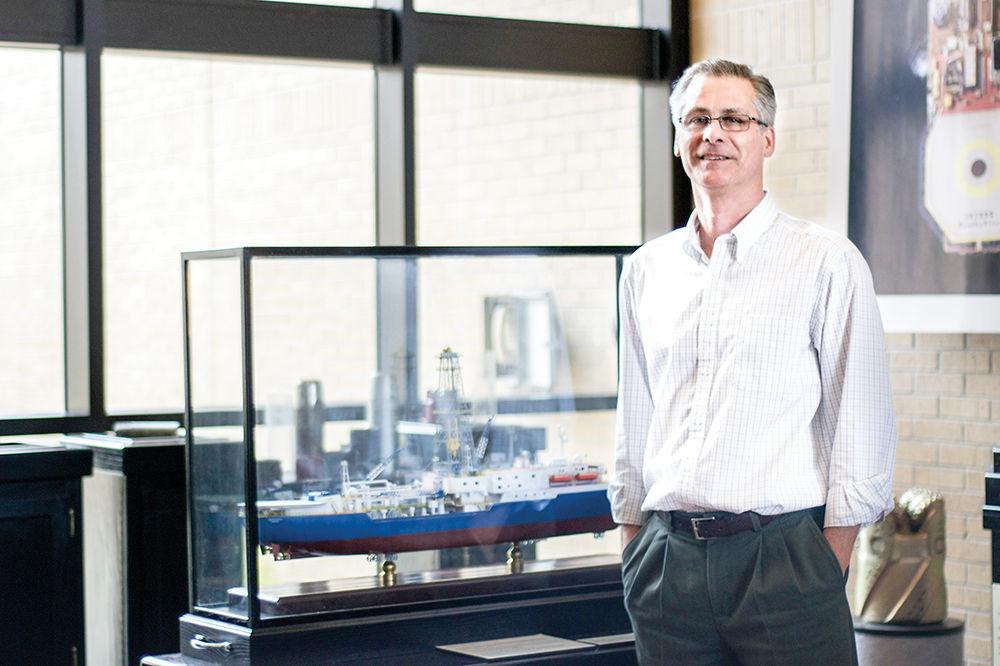

Phil Rumford, superintendent of the Gulf Coast repository, said the Earth’s ocean sediments contain a unique record of the planet’s history and structure. Through examining the sediments collected by the JOIDES Resolution, researchers work to answer questions such as what the global climate looked like 55 million years ago and how plate tectonics move.

Mitch Malone, assistant director of science services and manager of science operations, said 25 countries are participating.

“They send money to the U.S. so they can put their scientists on board,” Malone said.

Malone said expeditions go out every two months with a rotation of researchers and technicians. On the latest expedition, many of the staff in the IODP left for Sri Lanka to switch with their homebound counterparts to begin a new wave of drilling collections.

Serving as one of only three programs of its kind in the world, the IODP drills and maintains the largest collection of soil deposits from the Earth’s mantle extracted from the sub-ocean floor.

Drill bits cost between $12,000 and $17,000 per unit. Often, in harder sediment, the ship is only able to use a drill bit once before they have to attach another.

Collections are refrigerated on ship after a drilling to prevent molding. They’re sent back to the IODP library in College Station, where scientists who studied aboard the ship have a year’s unlimited access to the collections. After the year, tubes are free game to curious geologists, microbiologists and other scientists.

Comprised of more than 12,000 kilometers of clay, hard rock and softer sediments, Texas A&M’s branch of the IODP’s Library of Dirt is the only collection of its size in the nation.

Before the NSF gave the collection a boost in 1984, it began in 1966, when the NSF commissioned the Glomar Challenger, a drilling and coring ocean vessel, to collect deep-sea sediment. Now, thousands of rounded tubes of earth, microfossils and sediment line a giant refrigerator just inside the building.

Using the JOIDES Resolution, graduate students from A&M and researchers from around the world are able to drill earth cores from the ocean deep.

“IODP is all about looking at the history and structure of the earth using ocean drilling,” said Phil Rumford, superintendent of the Gulf Coast Repository and senior research associate at the IODP. “It’s a scientific program, and it’s not designed for oil. It’s purely geological research.”

Rumford said there are three main types of deep ocean sediment that the JOIDES collects.

“There’s carbonate-rich sediment, siliceous and red clays,” Rumford said. “The siliceous stuff you get in areas of upwelling, in high energy environments where warm and cold waters meet. There are a lot of nutrients there, so you get a lot of siliceous microfossils accruing in those kind of environments.”

Every centimeter of dirt equals one year, approximately, and one tube can contain hundreds of thousands of years and microbes skeletons. Microbiologists are able to look at the changes in micro-species as they examine a tube. Geologists can see changes in sediment, such as the change from red clay to harder volcanic mass, to determine underwater currents and volcanic activity beneath the seafloor.

Microbiologists are able to see the makeup of the fossils and determine how nutrient-rich a body of water was at any given time. Researchers are able to map nutrient flow by looking at the core and predicting what conditions that type of sediment would have formed under.

“Carbonate sediments are interesting because you get a lot of carbonate microfossils,” Rumford said. “When they settle onto the ocean floor, they create a carbonate compensation depth. Below the CCD carbonate doesn’t precipitate, it’s absorbed. Stuff like calcium carbonate is one of those weird things that is more soluble in cold water than it is in warm water.”

Malone said while researching the sediment, the scientists have to be careful not to contaminate it.

“We have to think about the fact that scientists later on might use this dirt for the same research topic or something completely different that nobody thought of 10 years later,” Malone said. “It’s a library of Earth’s history right there.”

The dirt on history: Campus houses international collection of ocean samples

April 7, 2015

0

Donate to The Battalion

$2790

$5000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas A&M University - College Station. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs, in addition to paying freelance staffers for their work, travel costs for coverage and more!

More to Discover