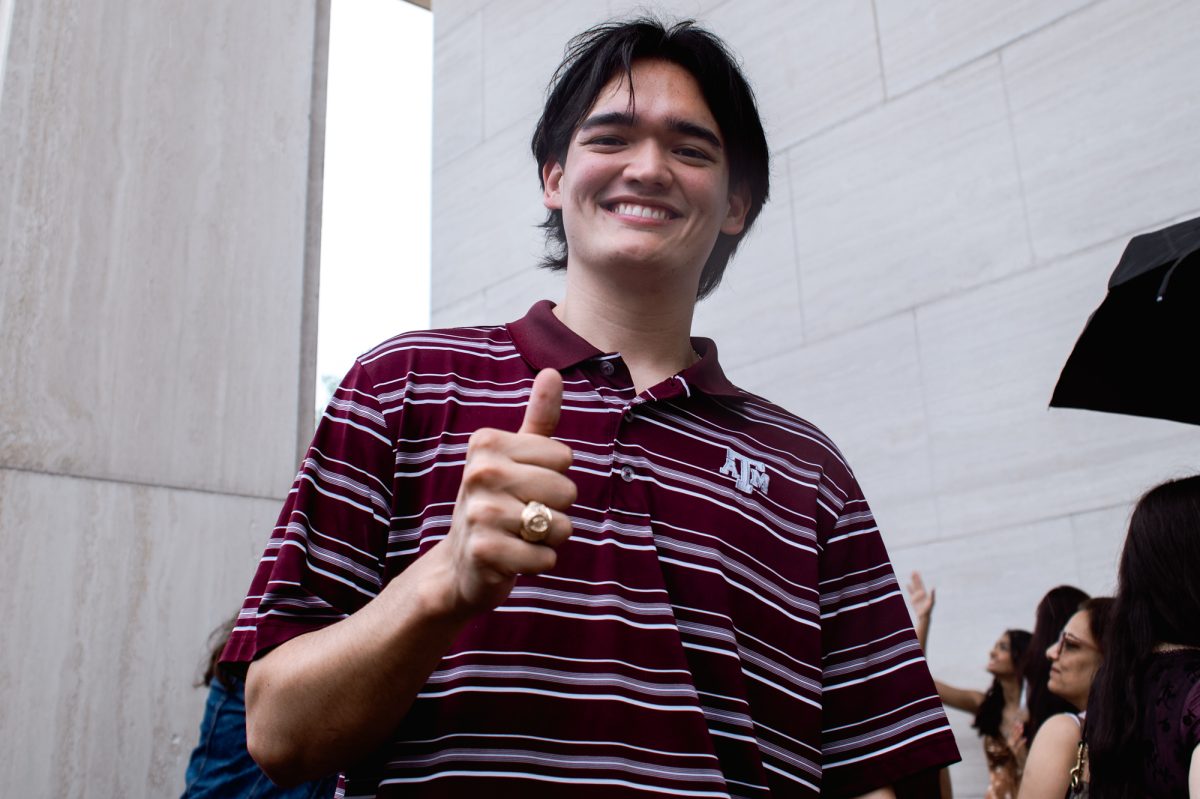

Born in Russia in 2001, Ivan Zabrodin grew up around many different cultures and people, always traveling and moving for his mother’s international oil and gas career.

“We spent a couple of years in Kazakhstan, then five years in Dubai, [United Arab Emirates,] three years in the United States. He was like a sponge, taking in the cultures and comparing them and being analytical,” his mother, Yulia Polovodova said. “In his mind, he was able to see the pros and cons in different societies. That was part of his personality — somebody who’s thinking all the time and analyzing and looking at the world objectively.”

Ivan was somebody who was looking for a sense of direction in his life, and he wanted to be useful and to serve others. Ivan aspired for his life to have a meaning.

After spending college away from friends and family during COVID-19, Ivan wanted to reconnect with the world, so just after his freshman year, he traveled to California.

“He spent a couple of months just walking with a backpack and sleeping at the small hotels and just absorbing the beauty or the nature,” Polovodova said. “I think it gave him force to go back to his status of searching for meaning.”

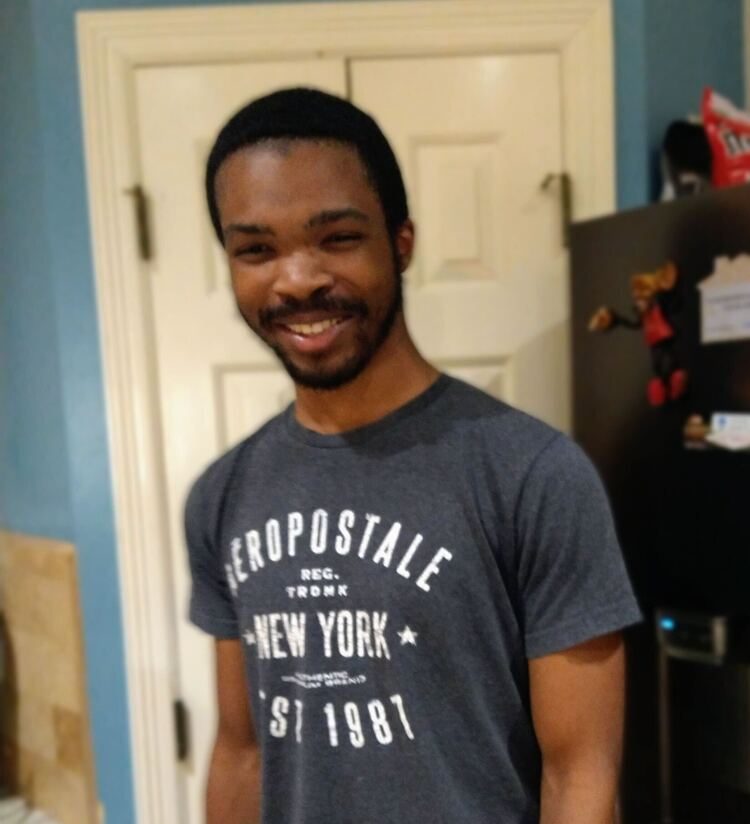

Ivan was a beautiful boy, inside and out, Polovodova said.

“He was really delicate, smart and had a tremendous sense of humor,” Polovodova said. “He was never really talkative or open to people. But he was very sensitive and very delicate, and he felt all sorts of things that were unusual, from my perspective, for a boy his age.”

Polovodova said a memory with Ivan she cherishes is when they were together on a trip in Scotland.

“We were together, just myself and him. We arrived in Glasgow, [Scotland] and took a car — it’s a [flipped] system on the road, so it was a little difficult for me to drive,” Polovodova said. “He decided to sit by my side and to just try to be in control — he was trying to support me. When I was having difficulties driving, he was always close by my side and he was comforting me.”

The car then had a tire problem and Polovodova said they were in the middle of nowhere in Glasgow, on an early Sunday afternoon. When she called the insurance company, they said they could only help if they went to a technical station — 70 miles away from where they were.

“So, Ivan stepped outside of the car and he tried to change the tire as a 10-year-old boy,” Polovodova said. “We attracted the attention of a gentleman who was passing by with his family. He helped us, but Ivan conducted himself like a very responsible person, not like a kid, but a man, helping his mother in this difficult situation. He was not a child at all.”

Another memory Polovodova closely cherishes is a time they were in Italy.

“We were in Rome, and he was just looking around, and he told me, ‘You know, this place is so beautiful. It almost hurts my feelings,’” Polovodova said.

As someone with a delicate personality, Ivan was incredibly perceptive of others. Because he traveled so much and had constantly changing surroundings from city to city, town to town and country to country, Polovodova said this made him even more intelligent, analytical and attentive.

Ivan played many musical instruments, most of which he taught himself on his own initiative.

“I never had to push him, he always chose himself,” Polovodova said. “He played the drums well, and it was his choice completely. One day he came to me and he said, ‘Mom, I want to try drums,’ and he never quit. He continued to play and play and play. He also composed music — nobody pushed him, nobody forced him. As a kid, he played chess, and he was very curious about life, in his own way. He didn’t like to party or meet a lot of people, but he would go into the depth of any subject he was interested in.”

Polovodova has a message for the Aggie community about the loneliness and lack of attention some college students with mental health problems are experiencing and about learning more about symptoms of depression and how to detect and prevent tragedies of suicide:

“If a student isn’t present at his classes for a semester, for three months … even for two weeks, that would immediately give a reason to call their family,” Polovodova said. “And [the school] needs to do something about it. They need to say, ‘Otherwise they will lose the opportunity to continue with us [at school],’ something like that. It’s prevention — in Ivan’s case, I think that this kind of information flowing to families could have saved his life.”

Attention to students is crucial, and Polovodova said this is especially true because depression often hits young, smart people.

“A person who’s never in a good mood, being distracted, absent, alone, not wanting to talk to anybody — sometimes it’s not a sign of somebody who doesn’t like friendships and parties,” Polovodova said. “Sometimes it’s a sign of a mental disease.”

Polovodova said depression is at times difficult to see because sometimes people like behaving themselves reasonably in terms of life decisions. But if one sees somebody is too emotional, too destructive or always in a bad mood, it’s a sign, and sometimes just a talk or conversation could save them.

“Ask, ‘Is everything good with you?’ or, ‘Are you suffering from any condition?’ Say, ‘Maybe you’re depressed, maybe you should see a doctor,’ or, ‘Maybe you should talk to somebody in your family,’ because sometimes students don’t speak to their families,” Polovodova said. “This is a normal symptom of depression. When people do not want to talk to their closest relations, sometimes a call to their family and telling them, ‘I’m anxious about your son or daughter, they seem to be depressed,’ could give them an opportunity to act before they do something awful to themselves. I would really like people and professors to be more attentive to students and more caring about students.”